The Safavid Dynasty: Iran's Golden Age of Cultural and Religious Transformation

Discover the remarkable legacy of the Safavid Dynasty (1501-1736), the powerful ruling house that transformed Iran's religious landscape, unified the nation, and created an unparalleled golden age of artistic achievement. From their Sufi origins to their enduring impact on modern Iranian identity, explore how this influential dynasty shaped Middle Eastern history through religious reformation, cultural patronage, and innovative governance.

HISTORYEDUCATION/KNOWLEDGE

Sachin K Chaurasiya

5/6/202513 min read

The Safavid Dynasty (1501-1736) stands as one of the most significant ruling houses in Iranian history, transforming the region's religious landscape and establishing a cultural identity that continues to influence modern Iran. This powerful dynasty unified Iran after centuries of fragmentation, established Twelver Shiism as the official state religion, and created a golden age of artistic and intellectual achievement. Their legacy remains deeply embedded in Iranian national identity and has shaped the geopolitical dynamics of the Middle East for centuries.

Origins and Rise to Power

The Safavid family traced their ancestry to Sheikh Safi al-Din (1252-1334), a Sufi leader who established the Safaviyya Sufi order in Ardabil, northwestern Iran. Originally a Sunni Sufi brotherhood, the order gradually adopted Shi'a beliefs and militarized under Sheikh Junayd and Sheikh Haydar in the mid-15th century.

Sheikh Junayd (1447-1460) transformed the order from a purely spiritual entity into a political-military force. His marriage to the sister of Uzun Hasan, leader of the Aq Qoyunlu confederation, established important political connections. His son, Sheikh Haydar, continued this militarization by introducing the distinctive red headgear with twelve folds (representing the twelve Shi'a Imams) that gave his followers the name "Qizilbash" or "red heads."

The dynasty's true founder, Ismail I, was merely 14 years old when he led his devoted Qizilbash followers to victory against the Aq Qoyunlu confederation in 1501. Following this triumph, Ismail proclaimed himself Shah and established Twelver Shiism as the official state religion, marking a pivotal moment in Islamic history.

Ismail's early campaigns were remarkably successful. Between 1501 and 1510, he conquered most of Iran, Iraq, and parts of eastern Anatolia. Contemporary accounts describe the charismatic young ruler as claiming divine status among his followers, who viewed him as the representative of the Hidden Imam—a messianic figure in Shi'a Islam.

Religious Transformation and Identity Formation

The Safavids' most consequential decision was establishing Twelver Shiism as the state religion in a predominantly Sunni region. This radical transformation required importing Shi'a scholars from Lebanon, Iraq, and Bahrain to develop religious institutions and convert the population. The process, sometimes enforced through coercion, fundamentally altered Iran's religious identity and created a distinct cultural boundary between Iran and its Sunni neighbors.

The conversion process was gradual and complex. Initially, there were few qualified Shi'a scholars in Iran, leading Shah Ismail to invite prominent Shi'a clerics like Shaykh Ali al-Karaki from Lebanon. These scholars helped establish religious educational institutions (madrasas), codify Shi'a jurisprudence, and train a new generation of indigenous Shi'a clergy.

By the end of the Safavid period, the religious establishment had developed sophisticated theological frameworks distinguishing Iranian Shi'ism from both Sunni Islam and other Shi'a communities. Concepts like the authority of mujtahids (religious scholars qualified to interpret Islamic law) and the integration of rational philosophy with religious doctrine became hallmarks of Safavid religious thought.

This religious policy served both spiritual and political purposes. It provided ideological coherence for the new state while distinguishing Safavid territory from the neighboring Ottoman Empire and Uzbek confederations, both adherents of Sunni Islam. This religious differentiation continues to influence regional geopolitics today.

Political Structure and Administration

The Safavid political system combined Persian administrative traditions with Turkic-Mongol military structures. At its height under Shah Abbas I (r. 1588-1629), the empire developed sophisticated governmental institutions:

The administration balanced several power centers:

The Shah, holding absolute authority as both political sovereign and religious leader

The Qizilbash tribal confederacy, providing military support

The Persian bureaucratic class, managing administrative affairs

The Shi'a religious establishment, providing religious legitimacy

The early Safavid state relied heavily on the Qizilbash tribal confederacy—Turkish-speaking nomadic tribes who formed the military backbone of the empire. Each tribe was led by a chief (amir) who commanded loyalty from his followers. This decentralized military structure provided tremendous fighting power but also created centrifugal tensions, as powerful amirs frequently challenged central authority.

Shah Abbas I implemented significant reforms that centralized power, weakened tribal influences, and established a slave corps (ghulams) loyal only to him. These ghulams, primarily drawn from converted Georgian, Circassian, and Armenian prisoners of war, formed an elite military and administrative corps that countered Qizilbash power. Abbas also created the position of wakil (regent) to oversee state affairs and established specialized administrative departments (diwans) for finance, royal lands, and religious endowments.

The Safavid administrative system divided the empire into provinces (wilayat) governed by appointed officials (beglerbegis). Local governance involved a complex network of officials, including kalantars (city mayors), darughas (police chiefs), and qazis (judges applying religious law). This administrative framework created relative stability and efficiency in governance compared to neighboring states.

Military Organization and Conflicts

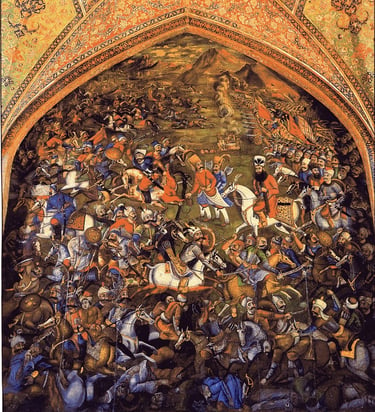

The Safavid military evolved significantly throughout the dynasty's existence. Initially dominated by Qizilbash cavalry using traditional steppe warfare tactics, the military faced serious challenges against Ottoman forces equipped with firearms and artillery. This technological disadvantage contributed to the devastating defeat at the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, where Ottoman Sultan Selim I crushed Shah Ismail's forces.

Learning from this defeat, Shah Tahmasp I (r. 1524-1576) began incorporating gunpowder weapons and artillery into Safavid forces. However, it was Shah Abbas I who fundamentally reformed the military by:

Creating a standing army of 37,000 troops paid directly from the royal treasury

Establishing the ghulam corps of slave soldiers trained in modern warfare

Incorporating musketeer infantry (tufangchis) armed with firearms

Developing an artillery corps with cannons manufactured in Isfahan

Adopting scorched earth tactics against Ottoman invasions

The Safavids faced three formidable enemies throughout their existence:

The Ottoman Empire to the west, competing for control of Iraq and the Caucasus

The Uzbek confederations to the northeast, threatening Khorasan province

The Mughal Empire to the east, occasionally disputing control of Kandahar

These ongoing conflicts drained resources and required maintaining large military forces. Despite facing these powerful adversaries simultaneously, the Safavids successfully defended their territory for over two centuries—a testament to their military capabilities and diplomatic acumen.

Economic and Commercial Development

The Safavid era witnessed remarkable economic vitality. A strategic location on trade routes between Europe and Asia positioned Safavid Iran as a commercial hub. Shah Abbas I's policies particularly encouraged economic growth through

Development of export industries, especially silk production and textiles

Construction of extensive network of caravanserais and roads

Relocation of the capital to Isfahan, transforming it into a magnificent commercial center

Establishment of trade relations with European powers, particularly England and the Dutch Republic

The silk industry formed the backbone of the Safavid export economy. Shah Abbas established a royal monopoly on silk trade, centralizing production and generating substantial revenue for the state treasury. He also encouraged Armenian merchants to settle in the new suburb of New Julfa in Isfahan, granting them privileges to facilitate international trade connections.

The Safavids created sophisticated economic institutions, including an extensive network of state workshops (karkhanas) producing luxury goods for both domestic consumption and export. These workshops manufactured textiles, carpets, ceramics, metalwork, and manuscripts under direct royal patronage, ensuring exceptional quality and artistic innovation.

The urban economy thrived with specialized bazaars organized by craft guilds (asnaf). These guilds regulated production standards, pricing, and apprenticeship systems while also providing social security for members. Urban commercial infrastructure included specialized commercial buildings such as qaysariyyas (high-end commercial complexes), timchas (trading halls), and sarais (merchant accommodation).

Foreign visitors frequently noted the prosperity of Safavid cities, with the French traveler Jean Chardin commenting that Isfahan rivaled Paris in size and grandeur during the 17th century. He estimated Isfahan's population at approximately 600,000—making it one of the world's largest cities at that time.

Urban Development and Architecture

Safavid rulers were prolific builders who transformed the urban landscape across their territories. Their architectural achievements combined Persian spatial concepts with Islamic geometric principles and innovative structural solutions.

Shah Abbas I's redesign of Isfahan represents the pinnacle of Safavid urban planning. The new city center, Naqsh-e Jahan Square (Image of the World), measured 512 by 159 meters, making it one of the largest public squares ever constructed. This monumental space integrated political, religious, and commercial functions with the royal palace (Ali Qapu), two magnificent mosques (Shah Mosque and Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque), and the entrance to the Imperial Bazaar all opening onto the square.

Beyond the capital, Safavid architectural patronage extended to numerous cities, including:

Qazvin, where Chehel Sotoun Palace set precedents for later Safavid palatial architecture

Mashhad, where the shrine of Imam Reza received extensive embellishment

Ardabil, where the dynasty's ancestral shrine complex was continuously expanded

Kerman, Shiraz, and Tabriz, which received significant religious and commercial buildings

Safavid architecture introduced several innovative features:

Haft Rangi (seven-color) tile work that allowed more complex decorative schemes

Double-shell domes that combined impressive exterior profiles with intimate interior spaces

Integration of gardens and water features into architectural compositions

Creative use of muqarnas (stalactite vaulting) for spatial transitions

Development of the Chaharbagh boulevard concept—tree-lined avenues divided by water channels

These architectural innovations influenced building traditions throughout the Islamic world, particularly in neighboring Mughal India.

Cultural Flowering and Artistic Achievement

The Safavid period represents the pinnacle of Persian cultural expression across numerous domains:

Architecture reached new heights with the magnificent redesign of Isfahan under Shah Abbas I. The city's grand Naqsh-e Jahan Square, surrounded by the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, Shah Mosque, and Ali Qapu Palace, exemplifies Safavid architectural brilliance, combining mathematical precision with aesthetic beauty.

Persian miniature painting achieved unprecedented sophistication during this period. Artists like Reza Abbasi developed distinctive styles characterized by delicate line work, vibrant colors, and intricate detail. These compositions often illustrated classical Persian poetry or depicted court life with remarkable precision.

The Safavid court atelier (kitabkhana) produced extraordinary illustrated manuscripts combining calligraphy, illumination, binding, and painting. Notable examples include the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp and the Khamsa of Nizami, which represent the height of Persian manuscript production. By the late Safavid period, single-page albums (muraqqa) containing poetry, calligraphy, and paintings became fashionable.

Carpet weaving transformed from a nomadic craft to a sophisticated urban industry under Safavid patronage. Court workshops designed complex patterns incorporating spiral vines, animal motifs, and hunting scenes. The famous Ardabil Carpet (now in London's Victoria and Albert Museum) exemplifies the technical perfection achieved by Safavid weavers.

Textile production flourished with silk brocades, velvets, and lampas weaves featuring intricate designs. These luxury textiles were highly valued internationally, with Safavid silk exported to Europe, Russia, and Asia. Similar patterns appeared across multiple media, creating a unified aesthetic language in Safavid visual culture.

Metalwork, ceramics, and book arts also thrived under royal patronage. Innovation in ceramic technology produced thin-bodied stonepaste wares with translucent glazes rivaling Chinese porcelain. Metalworkers created intricate inlaid brass and steel objects, combining functional elegance with decorative sophistication.

Literary achievements flourished as poets, philosophers, and theologians enjoyed royal patronage. Figures like Saib Tabrizi revitalized Persian poetry with innovative metaphors and novel imagery, while philosophers like Mulla Sadra developed comprehensive philosophical systems synthesizing various intellectual traditions.

Intellectual and Scientific Developments

The Safavid era witnessed significant intellectual achievements, particularly in philosophy, theology, and natural sciences. The period's intellectual atmosphere encouraged synthesis between various traditions:

The School of Isfahan, led by philosophers like Mir Damad and Mulla Sadra, developed the philosophical framework known as Hikmat (wisdom). This approach integrated Avicennan philosophy, Suhrawardi's illuminationism, Ibn Arabi's mysticism, and Shi'a theology into a coherent intellectual system. Mulla Sadra's magnum opus, "The Four Journeys" (Al-Asfar al-Arba'a), remains influential in Islamic philosophy to this day.

Theological developments under scholars like Muhammad Baqir Majlisi systematized Twelver Shi'a doctrine and practices. Majlisi's encyclopedia of Shi'a traditions, "Bihar al-Anwar" (Oceans of Light), compiled in 110 volumes, standardized religious knowledge and strengthened clerical authority.

Medical knowledge advanced through works like Muhammad Husayn Nurbakhsh's pharmacological treatise "Khulasat al-Tajarib" (Summary of Experiences), which documented thousands of medicinal compounds. Hospitals (bimaristans) in major cities served both as treatment centers and medical training institutions.

Mathematical and astronomical research continued previous Persian traditions. Observatories in Isfahan and elsewhere conducted celestial observations, while mathematical texts explored advanced algebraic concepts, practical geometry, and computational techniques.

Social Structure and Daily Life

Safavid society was hierarchically organized but allowed certain mobility based on merit, especially in administrative and religious spheres. The social structure included:

The royal family and high nobility, including Qizilbash chiefs and high-ranking officials

Religious scholars and clergy, whose influence increased throughout the Safavid period

Merchants and guild masters who controlled urban economies

Artisans and craftspeople organized into specialized guilds

Urban workers, shopkeepers, and service providers

Peasants who formed the majority of the population

Nomadic tribes who retained distinct lifestyles while acknowledging Safavid authority

Cities featured distinct quarters often organized by religious, ethnic, or occupational identity. Each quarter (mahalleh) had its own mosque, bathhouse (hammam), and small bazaar serving daily needs. Urban governance operated through quarter representatives (kadkhudas) who maintained order and represented their community to higher authorities.

Women's roles varied by social class and urban/rural divisions. Elite women could possess significant property and influence, sometimes participating in political affairs behind the scenes. Historical records document women as property owners, religious endowment administrators, and patrons of religious buildings. Lower-class urban women participated in domestic industries like spinning and weaving, while rural women contributed substantially to agricultural production.

Religious minorities, including Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians, held protected but subordinate status. Armenian Christians particularly prospered as international merchants, with Shah Abbas establishing the Armenian suburb of New Julfa in Isfahan as a center for international trade.

Decline and Legacy

Several factors contributed to the Safavid decline in the 18th century:

Military weakness and technological stagnation

Religious orthodoxy stifling intellectual innovation

Economic pressure from European maritime trade routes

Afghan invasion that captured Isfahan in 1722

Recurring succession crises and internal factional conflicts

Fiscal crises caused by declining trade revenues and expensive military campaigns

Climate change and drought affecting agricultural productivity

The final decades saw increasing decentralization as provincial governors and tribal leaders asserted independence from the weakening central authority. In 1722, a relatively small Afghan force under Mahmud Hotaki besieged Isfahan, leading to a catastrophic famine. When Shah Sultan Husayn surrendered in 1722, effective Safavid rule collapsed, though nominal Safavid rulers continued to claim the throne until 1736.

The dynasty officially ended in 1736 when Nader Shah Afshar, initially a Safavid military commander, established his own dynasty. Despite this political end, the Safavid legacy endures in modern Iran through:

Religious identity as a predominantly Shi'a nation

Cultural traditions in art, architecture, and literature

National consciousness and territorial boundaries

Administrative traditions and governance concepts

Diplomatic relations established with European powers

Architectural monuments that define Iranian cultural heritage

Artistic styles that continue to influence contemporary Iranian aesthetics

Religious educational institutions that evolved into the modern clerical establishment

International Relations and Diplomacy

The Safavids conducted sophisticated diplomatic relations with both neighboring powers and distant states:

Ottoman relations dominated foreign policy concerns, alternating between open warfare and tense peace. Major conflicts occurred under Shah Ismail I, Shah Tahmasp I, and Shah Abbas I, with the Treaty of Zuhab (1639) finally establishing relatively stable borders between the empires.

European diplomatic contacts intensified as the Safavids sought allies against the Ottomans. Shah Ismail exchanged correspondence with Charles V of Spain, while later Safavid rulers welcomed envoys from Portugal, England, France, and the Dutch Republic. These diplomatic missions often combined political, commercial, and religious objectives.

Particularly notable was Shah Abbas I's outreach to European powers. He:

Granted trading privileges to the English East India Company in 1616

Established diplomatic relations with various European courts

Sent diplomatic missions to European capitals, including an embassy to the courts of Eastern Europe in 1599

Welcomed European travelers, artisans, and mercenaries to his court

Relations with Mughal India fluctuated between alliance and rivalry. Cultural exchanges remained strong, with constant movement of artists, scholars, and merchants between the empires. The contested city of Kandahar changed hands multiple times as a symbol of shifting power dynamics.

Central Asian relations centered on containing Uzbek expansion while maintaining trade routes. Strategic alliances with Russian tsars against common enemies occasionally materialized, though geographic distance limited direct cooperation.

FAQ's

Who founded the Safavid Dynasty and when?

The Safavid Dynasty was founded by Shah Ismail I, who was only 14 years old when he led his Qizilbash followers to victory in 1501. While Ismail established the dynasty as a political entity, the spiritual foundations were laid by his ancestor, Sheikh Safi al-Din (1252-1334), who founded the Safaviyya Sufi order in Ardabil, northwestern Iran. The dynasty ruled from 1501 to 1736, spanning over two centuries of Iranian history.

Why was the Safavid Dynasty significant in Islamic history?

The Safavid Dynasty holds immense significance in Islamic history primarily because they established Twelver Shiism as the official state religion in a region that was predominantly Sunni. This religious transformation created a distinct Shi'a identity for Iran that persists to this day and fundamentally altered the religious map of the Middle East. The Safavids effectively created a religious and cultural boundary between Iran and its Sunni neighbors (the Ottoman Empire and Uzbek confederations), which continues to influence regional geopolitics in the modern era.

What were the major achievements of Shah Abbas I?

Shah Abbas I (r. 1588-1629), often considered the greatest Safavid ruler, transformed the empire through numerous achievements:

Relocated the capital to Isfahan and redesigned it into one of the world's most magnificent cities

Reformed the military by creating a standing army with slave soldiers (ghulams) loyal directly to him

Modernized the armed forces with firearms and artillery

Established a royal monopoly on silk trade, dramatically increasing state revenues

Developed extensive diplomatic relations with European powers

Patronized extraordinary architectural projects including the Naqsh-e Jahan Square complex

Defeated the Ottomans and Uzbeks, reclaiming lost territories

Reformed the administrative system to centralize power and reduce Qizilbash tribal influence

How did the Safavid Dynasty influence Persian art and culture?

The Safavid era represents a golden age for Persian cultural expression across multiple domains:

Architecture reached unprecedented heights with innovative designs combining mathematical precision with aesthetic beauty

Miniature painting evolved into a sophisticated art form with masters like Reza Abbasi developing distinctive styles

Carpet weaving transformed from a nomadic craft to a refined court art with complex patterns

Textile production, especially silk brocades and velvets, achieved technical perfection

Manuscript production combined calligraphy, illumination, and painting to create masterpieces like the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp

Poetry and literature flourished with innovative writers like Saib Tabrizi

Philosophical thought developed new syntheses under the School of Isfahan

Ceramic and metalwork production reached new levels of technical sophistication

What caused the decline and fall of the Safavid Dynasty?

Several interconnected factors contributed to the Safavid decline in the early 18th century:

Military weakness compared to advancing European powers and neighboring states

Increasing religious orthodoxy that stifled intellectual and technological innovation

Economic challenges as European maritime trade routes bypassed traditional overland paths

Climate change and drought affecting agricultural productivity

Succession crises and incompetent rulers in the late period

Fiscal crises due to declining trade revenues and expensive military campaigns

Decentralization as provincial governors and tribal leaders asserted independence

The Afghan invasion under Mahmud Hotaki that captured Isfahan in 1722, leading to catastrophic famine

How does the Safavid legacy continue to influence modern Iran?

The Safavid impact on modern Iran is profound and multifaceted:

The establishment of Twelver Shiism created Iran's distinctive religious identity that continues today

The territorial boundaries they consolidated largely align with modern Iran's borders

Their architectural monuments, particularly in Isfahan, remain powerful symbols of Iranian cultural achievement

Their synthesis of Persian cultural heritage with Shi'a religious identity forms the foundation of modern Iranian national consciousness

The religious educational institutions they established evolved into the modern clerical establishment

Their artistic styles continue to influence contemporary Iranian aesthetics

Their diplomatic relations with European powers initiated Iran's engagement with the Western world

The Safavid Dynasty fundamentally transformed Iranian society through religious reformation, cultural patronage, and state-building efforts. Their enduring legacy makes them not merely a historical dynasty but the architects of modern Iranian identity. The magnificent buildings, artistic masterpieces, and religious institutions they established continue to define Iranian cultural expression and national consciousness centuries after their political power faded.

The Safavids' greatest achievement was creating a coherent national identity combining Persian cultural heritage with Shi'a religious affiliation—a synthesis that remains central to Iranian self-perception today. Their territorial consolidation established boundaries remarkably similar to modern Iran, while their administrative innovations provided templates for later Iranian states.

The cultural flowering under Safavid patronage represents one of history's great artistic epochs, producing masterpieces that continue to inspire admiration worldwide. Their architectural monuments, particularly in Isfahan, remain among the world's most significant cultural treasures and powerful symbols of Iranian civilization.

Understanding the Safavid era provides essential context for comprehending contemporary Iran and regional dynamics in the Middle East. Their story demonstrates how a ruling dynasty can transcend political power to shape the spiritual, cultural, and national identity of a civilization for centuries to come.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚