The Ottoman Empire: Rise, Golden Age, and Legacy

Discover the fascinating story of the Ottoman Empire, one of history's most influential political entities. This comprehensive guide explores the empire's remarkable journey from a small principality to a global power that shaped the modern world across six centuries (1299-1922). Learn about its innovative governance systems, cultural achievements, and enduring impact on today's geopolitical landscape.

HISTORYEMPIRES/HISTORYEUROPEAN UNIONEDUCATION/KNOWLEDGE

Kim Shin

4/6/202512 min read

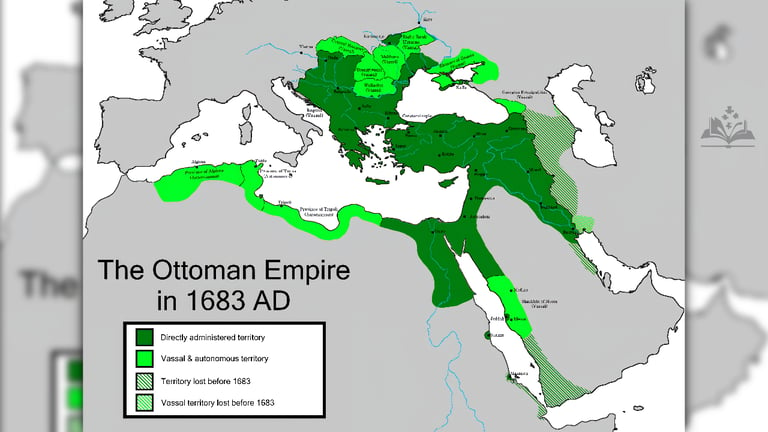

The Ottoman Empire stands as one of history's most influential and enduring political entities, spanning over six centuries from its humble beginnings in 1299 until its dissolution in 1922. At its zenith, this vast multicultural empire stretched across three continents, encompassing much of Southeastern Europe, Western Asia, and North Africa. The Ottomans created a unique civilization that blended Turkish, Islamic, Byzantine, and European influences, leaving an indelible mark on world history through their political innovations, cultural achievements, and religious policies.

Origins and Early Expansion

The Ottoman state began as a small principality in northwestern Anatolia, founded by Osman I, a Turkish tribal leader who gave the empire its name. Initially just one of many Turkish beyliks (small principalities) that emerged following the decline of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, the Ottomans distinguished themselves through military prowess and strategic vision.

Osman's successors, particularly his son Orhan and grandson Murad I, expanded Ottoman territories through conquest and marriage alliances. Their military success stemmed from the implementation of the devshirme system, which conscripted Christian boys from conquered territories into the empire's administration and military forces. The most elite of these recruits formed the Janissary corps—a highly disciplined infantry unit that would become the backbone of Ottoman military might for centuries.

The early Ottoman military excelled at frontier warfare, gradually absorbing neighboring territories through a combination of direct conquest and vassalage arrangements. Their adoption of gunpowder technology earlier than many European rivals gave them a significant tactical advantage. The Battle of Kosovo in 1389 and the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396 demonstrated Ottoman military superiority and cemented their control over the Balkans.

By the early 14th century, the Ottomans had crossed into Europe, establishing a foothold in the Balkans that would eventually grow into a substantial European presence. This eastward expansion created a multicultural empire at the crossroads of civilizations.

The Golden Age

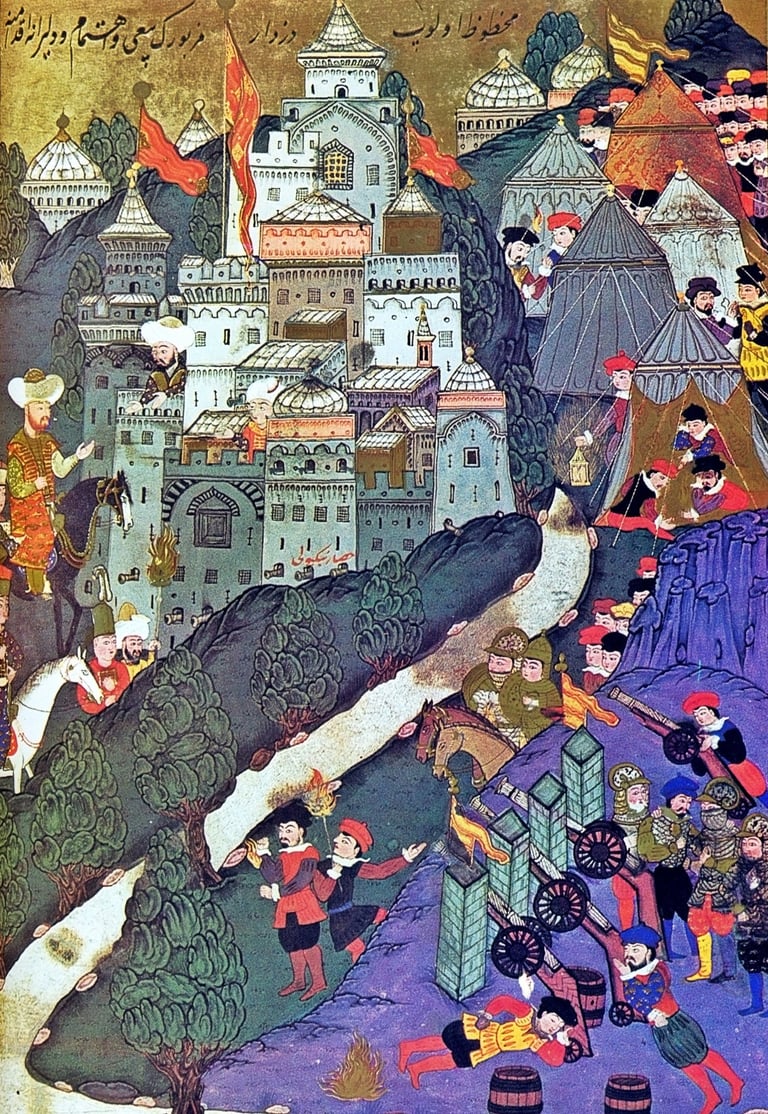

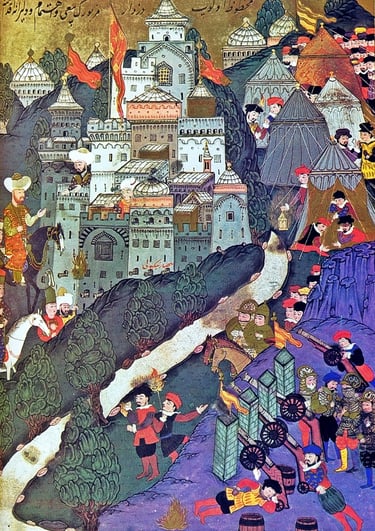

The conquest of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) in 1453 by Sultan Mehmed II, known as "the Conqueror," marked a watershed moment in Ottoman history. This victory over the Byzantine Empire established the Ottomans as a world power and provided them with a magnificent capital that would serve as the heart of their empire for nearly five centuries.

Following Constantinople's capture, Mehmed II embarked on an ambitious program to revitalize the city, rebuilding infrastructure, constructing mosques, and encouraging resettlement from diverse parts of the empire. He adopted the title "Caesar of Rome" (Kayser-i Rum), positioning himself as the legitimate successor to the Byzantine emperors and establishing a political ideology that blended Islamic and Roman imperial traditions.

The 16th century, particularly during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-1566), represented the pinnacle of Ottoman power and cultural achievement. Under Suleiman's leadership, the empire reached its greatest territorial extent, controlling territories from Hungary in the north to Yemen in the south and from Algeria in the west to the borders of Iran in the east.

Suleiman's reign witnessed significant codification of Ottoman law, earning him the title "Kanuni" (the Lawgiver) among his Turkish subjects. His comprehensive legal reforms standardized taxation, criminal punishment, and land management, creating a more predictable legal environment that fostered economic growth and administrative efficiency.

This period witnessed remarkable administrative efficiency, economic prosperity, and artistic flourishing. The Ottoman administrative system, with its intricate balance of central authority and local governance, proved remarkably effective at managing a diverse empire. The millet system granted religious communities significant autonomy in managing their internal affairs, allowing for peaceful coexistence among Muslims, Christians, and Jews.

Political Structure and Governance

The Ottoman political system centered on the sultan, who wielded absolute authority as both the political ruler and religious leader of the empire. The imperial harem played a crucial political role, particularly during periods when sultans were weak or disinterested in governance. The "Sultanate of Women" (Kadınlar Saltanatı) during the 16th and 17th centuries saw mothers, wives, and daughters of sultans exercising considerable influence over state affairs.

The imperial council, known as the Divan, served as the highest administrative body, bringing together key ministers to deliberate on matters of state. The Grand Vizier, as the sultan's chief minister, often wielded tremendous power in practical governance. The empire divided its territories into provinces (eyalets, later vilayets) administered by governors (beylerbeyi or valis) appointed by the central government.

The timar system, a form of land management that granted military officers control over agricultural revenues in exchange for military service, formed the economic backbone of Ottoman territorial control through much of the empire's history. This system provided the empire with a reliable provincial cavalry force without requiring direct financial outlay from the central treasury.

Economy and Trade

The Ottoman Empire controlled crucial trade routes connecting Europe, Asia, and Africa, allowing it to profit immensely from commerce. Istanbul, Aleppo, Cairo, and Izmir emerged as major commercial hubs where merchants from diverse backgrounds exchanged goods ranging from silk and spices to firearms and timber.

The empire's economic policy included careful regulation of prices (narh), guild systems (lonca) that maintained quality standards, and state monopolies over strategic commodities. Ottoman commercial law facilitated trade by providing relatively reliable mechanisms for contract enforcement and dispute resolution.

The Ottomans minted stable gold and silver currency, facilitating large-scale commerce across their territories. The central treasury (Hazine-i Amire) collected revenues through an elaborate taxation system that included the poll tax (cizye) on non-Muslims, agricultural taxes (öşür), customs duties, and occasional extraordinary levies.

By controlling key maritime chokepoints like the Bosporus, Dardanelles, and Red Sea, the Ottomans could influence global trade patterns. The empire granted capitulations (commercial privileges) to European powers, initially as diplomatic concessions from a position of strength, though these would later become economic liabilities as European commercial power grew.

Society and Culture

Ottoman society was characterized by religious tolerance relative to contemporary European powers, though non-Muslims paid special taxes and faced certain restrictions. The empire's cosmopolitan culture, particularly in cities like Istanbul, Aleppo, and Cairo, created environments where diverse traditions could interact and influence one another.

Social organization followed a hierarchical model, with the askeri (military-administrative) class exempt from taxation, while the reaya (productive subjects) bore the tax burden. Social mobility remained possible through education, military service, or administrative appointment, distinguishing Ottoman society from the more rigid class structures of feudal Europe.

The Ottoman court patronized a sophisticated high culture, including refined cuisine, elaborate ceremonies, and complex musical traditions. Palace music, performed by the Mehterhane (military band) for ceremonial occasions, influenced European classical composers including Mozart and Beethoven, who incorporated "Turkish" motifs into their compositions.

The Ottomans made significant contributions to architecture, with the magnificent mosques, palaces, and public buildings designed by architects like Mimar Sinan defining an enduring aesthetic. Ottoman calligraphy, miniature painting, poetry, and music all reached impressive heights, while the empire's patronage of sciences and medicine preserved and expanded upon classical knowledge.

Ottoman literature produced masterpieces in poetry and prose, with the divan tradition of palace poetry reaching its apex with figures like Baki, Fuzuli, and Nedim. Historical chronicles by writers such as Naima provided detailed accounts of Ottoman society and politics. The Seyahatname (Book of Travels) by Evliya Çelebi offers an invaluable first-hand perspective on 17th-century Ottoman life across the empire.

Daily life in the Ottoman Empire varied significantly depending on location, social class, religion, and time period. Urban centers featured vibrant markets (bazaars), public baths (hammams), and coffeehouses that served as centers for social interaction and information exchange. The empire's strategic position enabled extensive trade networks that connected Europe, Asia, and Africa, bringing prosperity and cultural exchange.

Religious Policies and Practices

Despite being an Islamic state where sharia formed the basis of the legal system, the Ottoman Empire developed sophisticated mechanisms for governing religious diversity. The millet system allowed recognized religious communities—primarily Orthodox Christians, Armenian Christians, and Jews—to manage their internal affairs according to their own religious laws and under their own religious leadership.

The sultans claimed the title of caliph, positioning themselves as successors to the Prophet Muhammad and protectors of Islam's holy sites. This religious legitimacy became increasingly important as the empire faced European Christian powers, particularly during the 16th-17th centuries, when religious identities hardened across Europe.

Sufi brotherhoods (tariqas) played a crucial role in Ottoman religious and social life, providing spiritual guidance, welfare services, and sometimes political influence. The Bektashi order maintained particularly close ties with the Janissaries, while the Mevlevi order (known for their whirling dervishes) enjoyed patronage from the imperial court.

Ottoman Islam developed its unique expressions, including the emergence of the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence as the empire's official legal interpretation. The imperial establishment maintained an uneasy relationship with more puritanical or radical Islamic movements, generally preferring pragmatic approaches that accommodated imperial realities.

Military Organization and Warfare

The Ottoman military system represented one of the most sophisticated fighting forces of its era. The Janissary corps, recruited through the devshirme system, constituted the empire's elite infantry and became one of the world's first standing armies. Armed with firearms and subjected to rigorous training, these troops gave the Ottomans a decisive advantage on European battlefields.

The Sipahi cavalry, supported by the timar land grant system, provided a mobile force that excelled in traditional warfare tactics. The Ottomans also maintained specialized military units like the Akıncı raiders, who conducted reconnaissance and harassing operations beyond the frontiers.

Ottoman naval power, built around galleys and later galleons, contested control of the Mediterranean with European powers. Admirals like Hayreddin Barbarossa and Piri Reis expanded Ottoman maritime influence and developed sophisticated cartographic knowledge. The naval arsenal in Istanbul, known as the Tersane-i Amire, ranked among the world's largest industrial complexes during the 16th century.

Artillery technology represented a particular Ottoman strength, with massive siege cannons enabling the conquest of previously impregnable fortifications. The imperial gun foundry produced high-quality bronze cannons that often surpassed European equivalents in reliability and power.

Decline and Modernization Efforts

By the late 17th century, the Ottoman Empire began experiencing military setbacks and internal challenges. The failed siege of Vienna in 1683 marked the beginning of a long period of territorial retreat in Europe. The Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) represented the first major territorial losses, forcing the Ottomans to cede Hungary and other territories.

Internal factors contributing to Ottoman decline included the deterioration of the timar system, corruption in administration, inflation triggered partly by the influx of American silver into global markets, and succession crises that sometimes paralyzed effective governance. The "Tulip Period" (1718-1730) under Ahmed III represented an early attempt at cultural renewal, though primarily within elite circles.

The 18th century saw the emergence of powerful local notables (ayan) who effectively controlled provincial administration, weakening central authority. Military defeats against Russia and Austria continued, while the rise of nationalism among subject peoples presented new challenges to imperial governance.

The 19th century brought ambitious reform efforts, beginning with the Tanzimat period (1839-1876), which aimed to modernize the empire along European lines. These reforms reorganized the military, education system, and legal codes. Sultan Mahmud II's abolition of the Janissary corps in 1826 (the "Auspicious Incident") removed a major obstacle to military modernization but also eliminated a powerful imperial institution.

The first Ottoman constitution was proclaimed in 1876, establishing a parliamentary system, though Sultan Abdülhamid II soon suspended it and ruled autocratically until 1908. During this period, the empire experienced significant educational and technological modernization, including the establishment of modern schools, railways, telegraph networks, and factories.

The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 and the subsequent constitutional period introduced further modernization efforts, but these came too late to reverse the empire's decline. Nationalist movements among Arabs, Armenians, Greeks, and other subject peoples gained momentum, while European powers increasingly interfered in Ottoman affairs.

Diplomacy and Foreign Relations

Ottoman diplomacy evolved from an initially assertive stance in the 15th-16th centuries to an increasingly defensive posture as European powers gained economic and military advantages. The empire skillfully played rival European states against one another, maintaining a balance of power that helped preserve Ottoman independence until the early 20th century.

The "Eastern Question"—how to manage the anticipated collapse of Ottoman power—dominated European diplomacy throughout the 19th century. Britain and France often supported Ottoman territorial integrity as a buffer against Russian expansion, while Russia consistently sought access to the Mediterranean through Ottoman territories.

The Crimean War (1853-1856) represented a rare diplomatic victory, as Britain and France allied with the Ottomans against Russia. However, the Congress of Berlin (1878), following the Russo-Turkish War imposed significant territorial losses, despite formal recognition of Ottoman sovereignty.

By the late 19th century, European powers had secured various forms of economic control within Ottoman territories through capitulations, foreign debt administration (the Ottoman Public Debt Administration), and direct investment in infrastructure like railways. Germany emerged as a key Ottoman ally, culminating in the fateful alliance in World War I.

Fall and Legacy

World War I delivered the final blow to the Ottoman Empire. Allying with Germany proved disastrous, and following defeat, the empire faced dismemberment under the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920. The Turkish War of Independence, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, rejected these harsh terms, and in 1922, the Ottoman sultanate was formally abolished. The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne recognized the new Republic of Turkey as the successor state.

The caliphate persisted briefly under Abdülmecid II until its abolition in 1924, ending the religious authority of the Ottoman dynasty. Members of the imperial family were exiled, returning to Turkey only decades later after restrictions were lifted.

The Ottoman collapse produced profound geopolitical consequences. The League of Nations established mandates over former Ottoman territories in the Middle East, with Britain controlling Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq, while France administered Syria and Lebanon. These arrangements laid the foundations for modern Middle Eastern states and contributed to ongoing regional conflicts.

The Ottoman legacy remains profoundly significant. The modern Middle East's political geography largely emerged from the empire's dissolution, with many current borders tracing back to post-Ottoman arrangements. Ottoman architectural and artistic traditions continue to influence cultural expression throughout former imperial territories. The empire's multiethnic, multireligious governance model, despite its imperfections, offers important historical lessons for diverse societies.

Ottoman administrative practices influenced governance throughout successor states. Turkish republican institutions built upon Ottoman precedents, even while officially rejecting imperial traditions. Legal codes, educational structures, and bureaucratic practices throughout the former empire often retained Ottoman elements despite nationalist reforms.

The Ottoman Empire in World History

In global historical context, the Ottoman Empire represented a crucial bridging civilization between East and West, serving as both a barrier and a conduit for cultural, technological, and economic exchange. Its control of trade routes linking Europe, Asia, and Africa positioned it as a key player in early modern globalization.

The Ottoman-European relationship defined much of early modern international relations, with Ottoman power directly influencing European political developments, from Habsburg imperial policy to the Protestant Reformation. European thinkers from Machiavelli to Montesquieu developed political theories partly in response to Ottoman governance models.

As a Muslim empire ruling substantial Christian and Jewish populations, Ottoman governance provided alternative models to the religious exclusivity that characterized most European states during the same period. The relative religious tolerance practiced by the Ottomans contrasted with contemporaneous European approaches, particularly during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation periods.

The Ottomans contributed significantly to global intellectual history, preserving classical knowledge and developing new insights in mathematics, astronomy, geography, medicine, and engineering. Scholars like Taqi al-Din produced astronomical observations and mechanical inventions that rivaled those of Tycho Brahe and other European contemporaries.

Historiography and Modern Understanding

Historical perspectives on the Ottoman Empire have evolved significantly over time. Early Western accounts often portrayed the empire as despotic and backward, reflecting geopolitical rivalries and religious prejudices. Colonial-era scholarship frequently emphasized Ottoman decline while downplaying the empire's adaptability and institutional strengths.

Nationalist historiographies in post-Ottoman states typically minimized positive aspects of Ottoman rule while emphasizing resistance to imperial control. Turkish republican historical narratives initially distanced modern Turkey from its Ottoman past, though recent decades have seen growing appreciation for Ottoman achievements.

Modern scholarship has substantially revised this picture, recognizing Ottoman governance as sophisticated and adaptable, with institutional strengths that enabled centuries of effective rule over diverse populations. Researchers increasingly approach Ottoman history on its own terms rather than through frameworks of "progress" or "backwardness" defined by European experiences.

Contemporary interest in Ottoman history has grown substantially, manifested in popular media ranging from television dramas to museum exhibitions. Digital humanities approaches are making Ottoman archival sources more accessible to researchers worldwide, enabling more nuanced understanding of this complex imperial system.

The Ottoman Empire's remarkable journey through six centuries of history demonstrates the complex interplay of political power, cultural achievement, and social organization within a vast multicultural state. From its dynamic rise to its gradual decline, the empire adapted to changing circumstances while leaving an enduring imprint on global history. Understanding the Ottoman experience provides valuable insights into religious coexistence, imperial governance, and the ongoing development of states and societies across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.

The Ottoman legacy challenges simplistic narratives about the relationship between Islam and modernity, demonstrating how an Islamic empire could incorporate diverse influences while maintaining its distinctive character. Its administrative innovations, cultural syntheses, and diplomatic strategies offer lessons that remain relevant for understanding contemporary global challenges.

Today, as nations that once formed part of this vast empire continue to navigate their unique paths forward, the Ottoman legacy remains relevant for understanding contemporary challenges and opportunities in these regions. The empire's rich cultural heritage, architectural marvels, and historical records continue to inspire researchers, artists, and visitors, ensuring that this remarkable chapter in human history remains alive in our collective memory.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚