The Ottoman Empire: A Comprehensive Guide to 600 Years of Imperial History

Discover the Ottoman Empire's 600-year legacy: from Constantinople's fall to WWI's end. Explore sultans, conquests, culture, and lasting global impact.

EMPIRES/HISTORYHISTORY

Kim Shin

1/17/202610 min read

Understanding the Ottoman Legacy

The Ottoman Empire stands as one of history's most enduring and influential civilizations, spanning six centuries across three continents. From its modest beginnings in 13th-century Anatolia to its dissolution in 1922, this Islamic empire shaped the political, cultural, and religious landscape of Europe, Asia, and Africa in ways that continue to resonate today.

This comprehensive guide explores the Ottoman Empire's rise, golden age, decline, and lasting impact on modern geopolitics, offering insights into how this once-mighty power influenced everything from architecture and cuisine to legal systems and international borders.

What Was the Ottoman Empire? Origins and Foundation

The Ottoman Empire (1299–1922) was a multi-ethnic, multi-religious empire that at its zenith controlled territories spanning southeastern Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa. Named after its founder, Osman I (Osman Gazi), the empire began as a small Turkish principality in northwestern Anatolia.

The Birth of an Empire: Osman I and Early Expansion

Osman I (reigned c. 1299–1323/4) established the dynasty that would bear his name during a period of fragmentation following the decline of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. Through strategic marriages, military conquests, and skillful diplomacy, Osman transformed his small beylik (principality) into the foundation of an imperial power.

Key factors in early Ottoman success included:

Strategic location: Positioned at the crossroads between Europe and Asia, the Ottomans controlled vital trade routes

Military innovation: Adoption of gunpowder technology and development of the Janissary corps

Religious tolerance: Pragmatic policies toward non-Muslim subjects that facilitated governance

Administrative efficiency: Development of the timar system for land management and military recruitment

The Rise to Power: Conquest and Consolidation (1299–1453)

Capturing Byzantine Territories

The early Ottoman sultans systematically expanded into Byzantine territory. Orhan I (1323/4–1362), Osman's son, captured Bursa in 1326, making it the first Ottoman capital. This conquest provided crucial resources and legitimacy to the emerging state.

Murad I (1362–1389) expanded Ottoman control into the Balkans, winning the pivotal Battle of Kosovo in 1389, which opened southeastern Europe to Ottoman rule. This expansion established a pattern that would define Ottoman strategy: simultaneous campaigns in both Europe and Asia.

The Fall of Constantinople: 1453

The conquest of Constantinople on May 29, 1453, by Sultan Mehmed II (known as Mehmed the Conqueror) marked a watershed moment in world history. This event ended the thousand-year Byzantine Empire and established the Ottomans as the preeminent power in the eastern Mediterranean.

Mehmed II employed innovative military tactics, including

Massive siege cannons designed by Hungarian engineer Orban

A naval maneuver that transported ships overland to bypass the Golden Horn's defenses

Sustained bombardment that breached the legendary Theodosian Walls

The renamed Istanbul became the Ottoman capital, transforming into a cosmopolitan center that would house Muslims, Christians, and Jews for centuries.

The Golden Age: Ottoman Empire at Its Peak (1453–1600)

Suleiman the Magnificent: The Lawgiver's Era

The reign of Suleiman I (1520–1566), known in the West as "the Magnificent" and in the Ottoman world as "the Lawgiver" (Kanuni), represents the empire's apex. During his 46-year reign, the Ottoman Empire reached its greatest territorial extent and cultural flourishing.

Territorial expansion under Suleiman included:

Conquest of Belgrade (1521) and most of Hungary following the Battle of Mohács (1526)

Siege of Vienna (1529), marking the furthest Ottoman advance into central Europe

Control of the eastern Mediterranean through naval dominance

Expansion into the Middle East, including Baghdad (1534)

Cultural and legal achievements:

Suleiman earned his title "Lawgiver" through comprehensive legal reforms that harmonized Islamic law (Sharia) with imperial decrees (kanun). He patronized the arts, architecture, and literature, presiding over what many consider the Ottoman classical age.

The architect Mimar Sinan created architectural masterpieces during this period, including the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, which rivals the earlier Hagia Sophia in grandeur.

Ottoman Society and Government Structure

The Ottoman administrative system represented a sophisticated bureaucracy that managed diverse populations across vast territories.

The Devshirme System: One of the most distinctive Ottoman institutions was the devshirme, a levy of Christian boys from Balkan provinces who were converted to Islam and trained for government or military service. This system produced the elite Janissary corps and many high-ranking officials, creating a meritocratic pathway to power independent of hereditary aristocracy.

The Millet System: Religious communities (millets) enjoyed significant autonomy under their own religious leaders. Christians and Jews, as "People of the Book," were protected as dhimmi, paying special taxes but maintaining their religious practices and internal governance.

Ottoman Military Power and Innovation

The Janissary Corps

The Janissaries (from Turkish "yeni çeri," meaning "new soldier") formed the empire's elite infantry units from the 14th to 19th centuries. Recruited through the devşirme system, these soldiers were trained from youth in military arts and Ottoman culture, becoming fiercely loyal to the sultan.

At their peak, the Janissaries numbered approximately 140,000 troops and represented one of the first standing armies in Europe since Roman times. However, by the 18th century, the corps had become politically powerful and resistant to reform, ultimately contributing to Ottoman military decline.

Naval Dominance in the Mediterranean

Under admirals like Hayreddin Barbarossa, the Ottoman navy controlled the Mediterranean during the 16th century. The Battle of Preveza (1538) established Ottoman naval supremacy, though the Battle of Lepanto (1571) marked a significant setback, ending the myth of Ottoman invincibility at sea.

Ottoman Culture, Art, and Architecture

Architectural Legacy

Ottoman architecture synthesized Byzantine, Persian, and Islamic traditions into a distinctive style. Key features included:

Large central domes inspired by Hagia Sophia

Slender minarets flanking major structures

Extensive use of İznik tiles with floral and geometric patterns

Complex mosque complexes (külliye) including schools, hospitals, and public kitchens

Notable architectural achievements include:

Hagia Sophia (converted to a mosque in 1453)

Süleymaniye Mosque (1557)

Blue Mosque (Sultan Ahmed Mosque, 1616)

Topkapı Palace (1465–1853)

Ottoman Arts and Literature

The Ottoman court patronized miniature painting, calligraphy, poetry, and music. The classical Ottoman poetry tradition, influenced by Persian forms, produced master poets like Fuzuli and Baki.

Ottoman miniature painting flourished in imperial workshops, documenting historical events, court life, and literary works. The Surname-i Vehbi, depicting the 1582 circumcision celebration for Prince Mehmed, exemplifies this artistic tradition.

Cuisine and Daily Life

Ottoman cuisine influenced and was influenced by the diverse cultures within the empire. Coffee culture, introduced from Yemen in the 16th century, became central to Ottoman social life. Coffeehouses emerged as important social and intellectual gathering spaces.

The Ottoman kitchen developed sophisticated dishes combining Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Balkan influences, creating a culinary legacy that continues in modern Turkish, Greek, Balkan, and Middle Eastern cuisines.

The Long Decline: Stagnation and Reform Attempts (1600–1922)

Military Defeats and Territorial Losses

The Ottoman Empire's decline was gradual, spanning over three centuries. Several factors contributed to this deterioration:

Military setbacks:

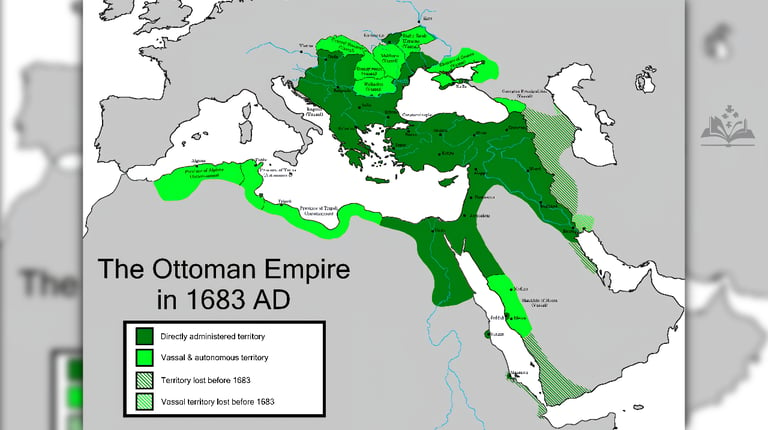

Failed Siege of Vienna (1683) and subsequent Treaty of Karlowitz (1699), which saw significant territorial losses to Austria

Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) following defeat by Russia, granting Russia protective rights over Orthodox Christians in Ottoman territory

Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), resulting in the loss of Greece

Crimean War (1853–1856), exposing Ottoman military weakness despite victory

The Tanzimat: Modernization Reforms

Recognizing the need for reform, Ottoman leaders initiated the Tanzimat period (1839–1876), meaning "reorganization" in Turkish. These reforms aimed to modernize the empire and prevent further decline.

Key Tanzimat reforms included:

Legal equality for all subjects regardless of religion

Modernization of the military along European lines

Educational reforms establishing secular schools

Administrative restructuring and anti-corruption measures

Establishment of the Ottoman Bank (1856)

First Ottoman Constitution (1876)

Despite these efforts, the reforms proved insufficient to reverse the empire's decline, often facing resistance from conservative religious and military factions.

The Young Turk Revolution

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), commonly known as the Young Turks, launched a revolution in 1908, restoring the suspended constitution and limiting the sultan's power. This movement represented Ottoman intellectuals' attempt to save the empire through nationalism and modernization.

However, the Young Turk period coincided with further territorial losses during the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) and culminated in the catastrophic decision to enter World War I on the side of the Central Powers.

World War I and the Empire's End

The Ottoman Empire in the Great War

The Ottoman Empire's entry into World War I in November 1914 proved fatal. Despite some victories, including the successful defense of Gallipoli (1915–1916), the empire suffered devastating defeats in multiple theaters.

Major WWI campaigns:

Gallipoli Campaign: Ottoman forces under Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) defeated Allied landings

Mesopotamian Campaign: Initial success at Kut but eventual loss of Baghdad and Mesopotamia

Sinai and Palestine Campaign: Loss of Jerusalem and Palestine to British forces

Caucasus Campaign: Conflict with Russia resulting in heavy Ottoman casualties

The Armenian Genocide

During World War I, the Ottoman government undertook systematic deportation and mass killings of Armenians, resulting in approximately 1.5 million deaths. This genocide remains a contentious historical issue, with Turkey disputing the characterization while most historians and many nations recognize it as genocide.

Dissolution and the Treaty of Sèvres

The Ottoman Empire officially ended with the abolition of the sultanate on November 1, 1922. The Treaty of Sèvres (1920) partitioned Ottoman territories among the Allies, but Turkish resistance led by Mustafa Kemal resulted in the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), which recognized the modern Turkish state's borders.

The caliphate was abolished in 1924, ending 1,300 years of Islamic caliphate tradition and establishing the secular Republic of Turkey.

Legacy and Impact on the Modern World

Political and Territorial Impact

The Ottoman Empire's dissolution created the modern Middle East's political map. British and French mandates drew borders that often ignored ethnic and religious divisions, contributing to ongoing regional conflicts.

Modern nations that emerged from Ottoman territory include:

Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Albania, Macedonia, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Kuwait, and parts of Ukraine and Russia.

Cultural and Religious Legacy

The Ottoman millet system influenced modern approaches to religious pluralism and minority rights. Ottoman legal concepts influenced civil law in successor states, while Ottoman Turkish remained the administrative language across much of the Middle East until the 20th century.

Istanbul's architectural heritage attracts millions of visitors annually, while Ottoman cuisine influences Mediterranean, Balkan, and Middle Eastern cooking traditions. Turkish coffee culture, hammam (bathhouse) traditions, and carpet weaving represent enduring Ottoman cultural exports.

Contemporary Relevance

Understanding the Ottoman Empire remains crucial for comprehending modern geopolitical conflicts in the Balkans, the Middle East, and the eastern Mediterranean. Issues including:

Sectarian conflicts in Iraq and Syria

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Kurdish autonomy questions in Turkey, Iraq, and Syria

Balkan ethnic tensions

Debates over secularism versus Islamism in Turkey

All have roots in Ottoman-era policies, borders, and population movements.

The Ottoman Empire's six-century span represents a crucial chapter in world history, bridging medieval and modern eras, East and West, and Islam and Christendom. Its sophisticated administrative systems, cultural achievements, and territorial reach shaped the development of Europe, Asia, and Africa in profound ways that continue to influence contemporary geopolitics.

Understanding the Ottoman Empire provides essential context for comprehending modern conflicts, borders, and cultural dynamics across three continents. From the architectural splendors of Istanbul to ongoing debates about secularism and religious identity in Turkey, from Middle Eastern borders drawn after the empire's fall to Balkan ethnic complexities, the Ottoman legacy remains remarkably relevant.

For students of history, international relations, religious studies, or cultural anthropology, the Ottoman Empire offers invaluable lessons about imperial governance, cultural synthesis, religious tolerance and intolerance, the challenges of reform and modernization, and the long-term consequences of an empire's rise and fall. As we navigate an increasingly interconnected world, the Ottoman experience—both its successes in managing diversity and its failures in adapting to change—provides timeless insights into the complexities of power, culture, and identity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How long did the Ottoman Empire last?

The Ottoman Empire lasted approximately 623 years, from its founding around 1299 under Osman I until its formal dissolution in 1922 when the Turkish Grand National Assembly abolished the sultanate.

Q: What was the largest extent of the Ottoman Empire?

At its territorial peak in the late 16th and early 17th centuries under Suleiman the Magnificent and his successors, the Ottoman Empire controlled approximately 5.2 million square kilometers (2 million square miles), spanning southeastern Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa, from modern-day Algeria to the Persian Gulf and from Hungary to Yemen.

Q: Why did the Ottoman Empire fall?

The Ottoman Empire's decline resulted from multiple interconnected factors: military defeats to European powers with superior technology, economic stagnation compared to industrializing European nations, internal corruption and political instability, the rise of nationalism among subject peoples, the failure of reform efforts to adequately modernize institutions, and the catastrophic decision to enter World War I on the losing side.

Q: What religion was the Ottoman Empire?

The Ottoman Empire was an Islamic state with Sunni Islam as the official religion. However, it practiced relative religious tolerance through the millet system, allowing Christian and Jewish communities significant autonomy in managing their internal affairs while paying special taxes.

Q: Who was the most powerful Ottoman sultan?

Suleiman I (the Magnificent/the Lawgiver), who ruled from 1520 to 1566, is generally considered the most powerful Ottoman sultan. His reign marked the empire's political, military, and cultural zenith, with successful military campaigns, territorial expansion, comprehensive legal reforms, and unprecedented cultural flowering.

Q: What was the capital of the Ottoman Empire?

The Ottoman Empire had several capitals throughout its history. Söğüt and Bursa served as early capitals, followed by Edirne (1363–1453). Constantinople (renamed Istanbul after its conquest in 1453) became the final and most famous capital, remaining so until the empire's end in 1922.

Q: How did the Ottoman Empire treat non-Muslims?

Non-Muslims, particularly Christians and Jews recognized as "People of the Book," were granted dhimmi status with legal protections under the millet system. While they paid additional taxes (jizya) and faced certain restrictions, they enjoyed religious freedom and internal community governance and could achieve high positions in government and commerce. Treatment varied across time periods and locations, with some eras showing greater tolerance than others.

Q: What caused the fall of Constantinople in 1453?

Constantinople fell due to Sultan Mehmed II's innovative siege tactics, including massive cannons that breached the city's famous walls, a daring maneuver transporting ships overland to bypass naval defenses, sustained bombardment over 53 days, numerical superiority of Ottoman forces, and Byzantine inability to secure adequate external assistance despite desperate appeals to Western European powers.

Q: What was the devshirme system?

The devshirme was a unique Ottoman practice of recruiting Christian boys from Balkan provinces, converting them to Islam, and training them for elite military (Janissary corps) or administrative service. This system created a meritocratic pathway to high positions independent of hereditary nobility, though it represented a significant burden on Christian communities who lost their sons to forced conversion and service.

Q: How did the Ottoman Empire influence modern Turkey?

Modern Turkey directly succeeded the Ottoman Empire, inheriting much of its core Anatolian territory. However, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk deliberately broke with Ottoman traditions, abolishing the caliphate, establishing secularism, adopting Western legal codes, changing the alphabet from Arabic to Latin script, and promoting Turkish nationalism over Ottoman multi-ethnic identity. Despite these reforms, Ottoman cultural influences remain visible in Turkish architecture, cuisine, music, and social customs.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚