The Yuan Dynasty: China's Era of Mongol Rule (1271-1368)

Explore the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), when Mongol conquerors led China through transformative change, creating unprecedented global connections and cultural innovations that reshaped East-West relations. This comprehensive analysis examines the rise, governance, cultural achievements, and lasting legacy of this pivotal period in Chinese history.

CHINESE HISTORYHISTORYEDUCATION/KNOWLEDGEINDIA & CHINE

Kim Shin

3/31/202518 min read

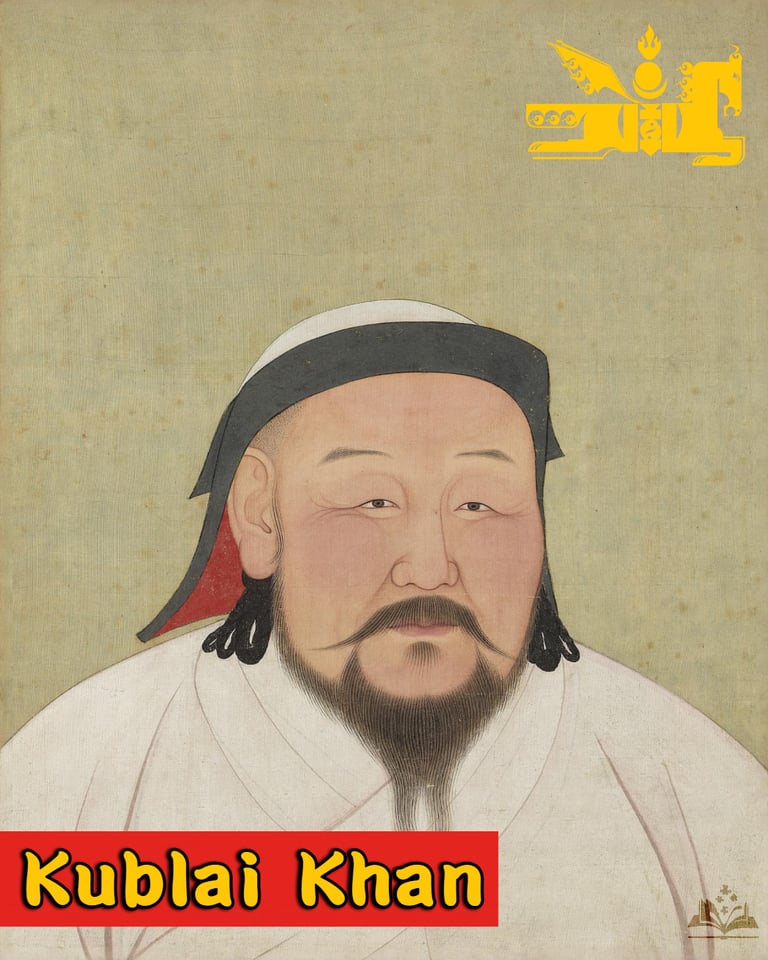

The Yuan Dynasty stands as one of the most fascinating chapters in China's long and storied history. Established by Kublai Khan, grandson of the legendary Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan, this dynasty represented the first time that China fell completely under foreign rule. The Yuan period brought unprecedented global connections, dramatic cultural exchanges, and significant administrative innovations that would influence Chinese governance for centuries to come. This article explores the rise, governance, cultural developments, and eventual decline of the Yuan Dynasty, offering insights into this transformative period that bridged East and West in ways previously unimaginable.

Historical Context and the Rise of Mongol Power

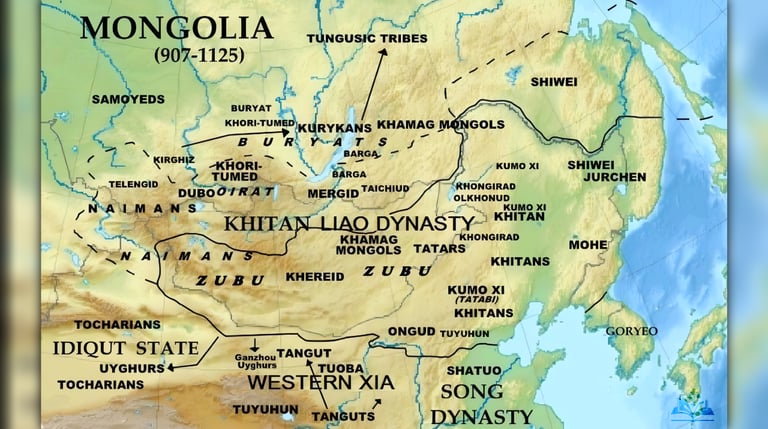

Before the Mongols' arrival, China was divided between the Jin Dynasty in the north and the Song Dynasty in the south. The Mongol conquest of China didn't happen overnight; it was a gradual process spanning several decades. Genghis Khan initiated military campaigns against the Jin Dynasty in northern China beginning in 1211, but it was his grandson Kublai who would complete the conquest and establish formal dynastic rule.

The Mongol military machine that enabled this conquest was a revolutionary force in medieval warfare. The Mongol cavalry represented the perfect combination of mobility, discipline, and firepower (in the form of composite bows). Their military tactics—including feigned retreats, coordinated flanking maneuvers, and psychological warfare—overwhelmed enemies accustomed to more conventional fighting styles. By the time they reached China, the Mongols had already conquered vast territories from Korea to Eastern Europe, learning and adapting new siege technologies necessary for taking fortified Chinese cities.

Kublai Khan proclaimed the Yuan Dynasty in 1271, though the conquest of the Southern Song wasn't completed until 1279. This final victory marked the first time in history that all of China proper had fallen under Mongol dominance, creating the largest contiguous empire the world had ever seen.

Kublai Khan: Architect of the Dynasty

Kublai Khan deserves special attention as the true architect of the Yuan Dynasty. Unlike his grandfather Genghis, who remained primarily a steppe conqueror, Kublai transformed himself into a Chinese-style emperor while maintaining his Mongol identity. His dual approach to governance—ruling Mongols according to Mongol traditions while adopting Chinese imperial practices for his Chinese subjects—demonstrated remarkable political acumen.

Kublai's decision to establish his capital at Dadu (modern-day Beijing) rather than Mongolia signaled his commitment to ruling China as a legitimate dynasty. The city was designed as an impressive imperial capital, combining Chinese and Mongol elements. Marco Polo's descriptions of Kublai's court reveal lavish ceremonies, grand architecture, and administrative complexity that impressed even visitors from sophisticated European cities.

While embracing aspects of Chinese culture, Kublai maintained Mongol traditions through seasonal hunts, special areas reserved for Mongol pastoralism, and the preservation of the Mongol language for official purposes among the elite. This cultural balancing act characterized the entire Yuan period.

Government and Administration

The Yuan Dynasty introduced a unique administrative system that reflected both Mongol traditions and practical adaptations to governing the sophisticated Chinese state:

Social Hierarchy

The Yuan established a rigid four-tiered social hierarchy that placed Mongols at the top, followed by Central Asians (called "Semu" or "colored-eye people"), then northern Chinese, and finally southern Chinese (former subjects of the Song Dynasty) at the bottom. This system created deep resentments among the Chinese population that would eventually contribute to the dynasty's downfall.

The policy had practical implications beyond mere status. Chinese were prohibited from learning the Mongol language, owning weapons, or gathering in groups. Advancement in government service—traditionally the path to social mobility in China—became much more restricted for ethnic Chinese, especially those from the south.

Administrative Innovations

Despite imposing ethnic stratification, the Yuan implemented several governmental innovations:

Creation of the Secretariat (Zhongshu Sheng) as the central governing body

Division of the empire into provinces (a structure adopted by later dynasties)

Establishment of specialized government agencies for commerce, transportation, and other activities

Integration of Chinese, Muslim, and other foreign experts into government service

Implementation of a postal relay system (yam) that connected the vast empire with impressive efficiency

Creation of the Censorate, an institution designed to monitor government officials and report corruption

The Mongols' outsider perspective allowed them to reform aspects of Chinese government that had become inefficient under previous dynasties. They were less bound by traditional Chinese bureaucratic practices and could implement pragmatic solutions drawing on diverse administrative traditions from across their empire.

Legal System

The Yuan legal system represented a complex hybrid of Mongol customary law (the Yassa) and Chinese legal traditions. Different ethnic groups were often subject to different laws and punishments, with Mongols typically receiving lighter sentences for comparable crimes. This legal pluralism created administrative challenges but allowed the Mongols to maintain their own traditions while governing a diverse empire.

Criminal punishments during the Yuan era were often harsh by modern standards but included innovative approaches like the use of paper currency for fines and compensation payments. The legal system also incorporated elements from Islamic law in areas with significant Muslim populations, demonstrating the multiethnic nature of Yuan governance.

Economic Developments

The Yuan Dynasty transformed China's economy in profound ways:

Trade and Commerce

Under Mongol rule, the famous Silk Road reached its zenith. The "Pax Mongolica" (Mongol Peace) created unprecedented safety for merchants traveling across Eurasia. For the first time, direct trade links connected China with Persia, Russia, and parts of Europe. Merchants from as far away as Venice and Genoa established trading posts in Chinese cities.

The Mongols actively encouraged this international trade by

Providing military protection for merchant caravans

Establishing standardized weights, measures, and currencies

Creating a network of caravanserais (rest houses) along major trade routes

Offering tax incentives to merchants

Appointing merchant representatives (ortaq) who served as commercial agents for the Mongol elite

These policies transformed China's economic orientation, making it more outward-looking than it had been under previous dynasties. Foreign goods—including spices, gems, horses, and exotic animals—flowed into China, while Chinese silk, porcelain, and manufactured goods reached markets across Eurasia.

Paper Money

The Yuan significantly expanded the use of paper currency (first introduced under the Song). Government-issued bills called "chao" became the standard currency throughout the empire, representing one of the world's first experiments with fiat money on a large scale.

The sophisticated Yuan monetary system included notes in different denominations, with elaborate security features to prevent counterfeiting. The notes contained serial numbers, official seals, and warnings about the severe punishments awaiting counterfeiters. Initially, the system functioned effectively, facilitating trade across the vast empire. However, later Yuan rulers' excessive printing of money led to inflation that undermined public confidence in the currency.

Agricultural Policies

The Mongols, originally pastoralists, had to learn to manage China's complex agricultural economy. They initiated irrigation projects, encouraged the spread of drought-resistant crops from Central Asia, and temporarily reduced tax burdens on farmers after years of warfare.

The Yuan government established the Office of Stimulation of Agriculture to improve farming techniques and increase production. They introduced new strains of fast-ripening rice from Champa (modern Vietnam) that could produce multiple harvests annually. Persian irrigation technologies, including the use of the screw pump and improved water wheels, were also introduced to Chinese agriculture during this period.

Maritime Trade and Naval Developments

While the Silk Road typically receives more attention, the Yuan period also saw significant developments in maritime trade. The government invested in improving port facilities at Quanzhou (known to Western traders as Zayton) and other coastal cities. Chinese ships carried goods to Southeast Asia, India, and even East Africa.

Naval technology advanced considerably, with improvements in shipbuilding, navigational techniques, and maritime charts. These developments laid important foundations for the famous Ming Dynasty voyages of Zheng He in the following century. The maritime Silk Road became an increasingly important complement to overland trade routes.

Cultural and Scientific Achievements

Despite being conquered by nomadic warriors, China's cultural development continued and in some areas accelerated during the Yuan period:

Sciences and Technology

The Yuan era saw remarkable developments in astronomy, mathematics, and medicine, often through the cross-fertilization of Chinese, Islamic, and European knowledge. The Yuan court established the Islamic Astronomical Bureau alongside the traditional Chinese one, allowing for comparison and synthesis of different astronomical traditions.

Notable scientific achievements included:

Guo Shoujing's improved calendar system and astronomical instruments

The integration of Arabic numerical systems and algebraic methods with traditional Chinese mathematics

Advances in mechanical engineering, including Guo Shoujing's water clock and hydraulic trip hammers

Refinements in gunpowder weapons, including early cannons and explosive projectiles

Development of improved techniques for textile production, including advanced looms

Medical exchanges that brought Persian and Arab pharmacology into contact with traditional Chinese medicine

The Yuan government sponsored extensive encyclopedic projects to preserve and organize knowledge, producing works like the "Jingshi Dadian" (Compendium of Governance) that compiled information on history, administration, and science.

Literature and Theater

Chinese drama reached new heights during the Yuan period. The "zaju" theatrical form, featuring four acts with songs and spoken dialogue, became immensely popular. Many of China's greatest dramatic works, including "The Romance of the Western Chamber" and "The Orphan of Zhao," date from this era.

The Mongol conquest disrupted traditional civil service examination pathways for educated Chinese, paradoxically freeing many scholars to pursue literary careers. Playwrights like Guan Hanqing, Wang Shifu, and Ma Zhiyuan produced works that remain classics in Chinese literature. These plays often focused on ordinary people rather than aristocrats, reflecting broader social changes during the Yuan era.

Poetry also flourished, with writers like Yu Ji, Yang Weizhen, and Zhang Kejiu creating new styles that combined classical Chinese traditions with fresh themes and approaches. The "sanqu" form—a type of lyrical poetry set to popular tunes—became especially prominent during this period.

Vernacular literature gained unprecedented importance during the Yuan. While classical Chinese remained the language of government and scholarship, works in vernacular Chinese reached wider audiences and developed new narrative techniques that would influence later Chinese novels.

Visual Arts

Yuan painters often expressed their feelings about Mongol rule through their art. The most famous Yuan painters, including Zhao Mengfu and the "Four Masters of the Yuan" (Huang Gongwang, Wu Zhen, Ni Zan, and Wang Meng), developed styles emphasizing personal expression and a return to classical Chinese artistic values. Their landscape paintings often featured scenes of retreat into nature, possibly reflecting their ambivalence about government service under foreign rulers.

Porcelain production reached new technical heights during the Yuan, with the famous blue-and-white porcelain developing its distinctive style through the combination of Chinese craftsmanship with imported cobalt pigments from Persia. The Yuan government established the Fuliang Porcelain Bureau to oversee ceramic production at Jingdezhen, which became the center of China's porcelain industry.

Textile arts also flourished, with new techniques for silk weaving and embroidery. The influence of Central Asian decorative patterns is evident in surviving textiles from this period, showing dragons, phoenixes, and floral motifs arranged in novel compositions that reflected the multicultural nature of the Yuan realm.

Religious Policy

The Yuan Dynasty practiced remarkable religious tolerance compared to many contemporaneous regimes. Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, Christianity (in the form of Nestorianism), and other faiths coexisted within the empire. Tibetan Buddhism received particular imperial patronage, establishing connections between China and Tibet that continue to this day.

Religious institutions often received tax exemptions and land grants under Mongol rule. The White Pagoda of Beijing's Miaoying Temple, built under Kublai Khan's patronage in 1279, stands as a physical reminder of imperial support for Tibetan Buddhism. Muslim communities flourished in urban centers, building mosques and maintaining their religious practices while serving in the Yuan administration.

This religious pluralism wasn't merely tolerance; it reflected the Mongols' pragmatic approach to governance and their belief that different deities could be appeased simultaneously to ensure divine favor for the empire. Religious leaders from various traditions were regularly consulted on matters of state ritual and occasionally served as diplomatic representatives.

Urban Life and Social Changes

Urban Development

Major cities underwent extensive reconstruction under Mongol rule. Dadu (Beijing) was designed as a grand imperial capital, with wide avenues, artificial lakes, and impressive palaces that reflected Mongol concepts of urban planning combined with Chinese architectural techniques. The city's layout, with its north-south axis and rectangular grid pattern, established templates that would influence Beijing's development for centuries to come.

Other major urban centers, including Hangzhou (the former Southern Song capital) and Quanzhou (a major port city), maintained their economic importance but adapted to new political realities. Each major city typically contained distinct quarters for different ethnic communities, with Mongols and Central Asians often occupying privileged central areas near administrative buildings.

Daily Life

For ordinary Chinese, daily life under Yuan rule presented a complex mixture of continuity and change. In rural areas, traditional patterns of village life and agriculture continued with relatively little direct Mongol influence. Urban residents, however, experienced more significant changes as they encountered Mongol rulers, Central Asian merchants, and foreign goods.

Clothing styles, culinary practices, and entertainment forms all reflected increasing cultural hybridization. The traditional Chinese long gown was modified under Mongol influence to include elements like the front-opening jacket. New foods entered the Chinese diet, including dairy products more commonly consumed by steppe peoples. Musical instruments from Central Asia, including the huqin (a fiddle) and the pipa (a lute), became increasingly popular in Chinese musical traditions.

Social Mobility

The Yuan's ethnic classification system created new patterns of social mobility. While traditional Chinese examination-based advancement became more restricted, new opportunities emerged for individuals with linguistic skills, commercial connections, or technical expertise valuable to the Mongol rulers. Merchants, previously accorded relatively low status in Confucian social hierarchies, gained unprecedented prestige and influence under the commerce-friendly Mongols.

Religious institutions also offered alternative paths for advancement, with Buddhist and Daoist monasteries, Islamic schools, and other religious organizations providing education, community leadership positions, and connections to wider networks beyond China's borders.

Cultural Exchange and Global Connections

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the Yuan Dynasty was its role in facilitating unprecedented global connections:

European Contacts

The Yuan period saw the first significant direct contacts between China and Europe. The most famous visitor was Marco Polo, who reportedly served at Kublai Khan's court for 17 years. Though debate continues about the accuracy of his account, Polo's descriptions of China's wealth and sophistication captivated European imaginations for centuries.

Other European travelers included John of Montecorvino, the first Catholic archbishop in China, who established a cathedral in Khanbaliq (Beijing) and translated the New Testament and Psalms into Mongolian. Merchants like Francesco Pegolotti compiled detailed commercial handbooks describing routes to China and business practices there, reflecting growing European interest in direct trade with East Asia.

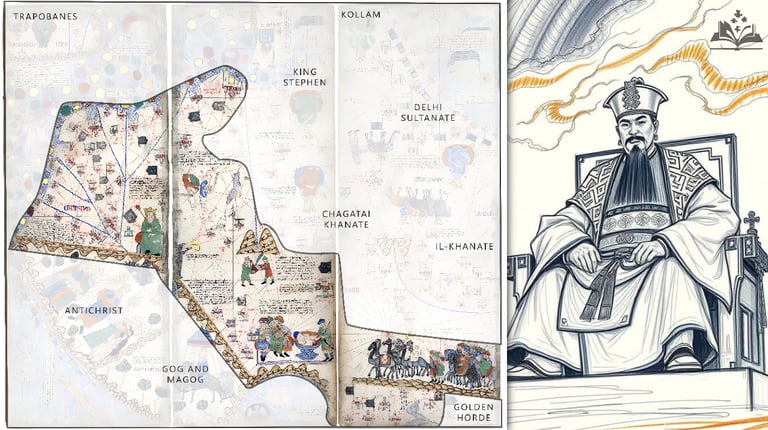

These contacts had lasting impacts on European conceptions of China and Asia more broadly. Cartographic knowledge improved significantly, with maps like the Catalan Atlas of 1375 showing a relatively accurate representation of Asia based partly on information from travelers who had visited the Yuan realm.

Persian and Islamic Influence

Muslim officials, scientists, and artists held prominent positions in the Yuan government. Persian astronomical knowledge, medical practices, and artistic motifs entered China during this period. The Islamic communities established in Chinese cities during the Yuan continue to be an important part of China's cultural mosaic.

The most famous Muslim figure in Yuan China was Sayyid Ajall Shams al-Din Omar, who served as governor of Yunnan province and exemplified the multicultural nature of the Mongol administration. Under his governance, irrigation systems were improved, schools were established, and diverse religious communities coexisted peacefully. His descendants remained influential in Chinese society for generations.

Islamic architectural influences can be seen in surviving Yuan-era buildings, particularly in the use of domes, arches, and glazed tile decoration. Persian miniature painting techniques influenced some Chinese artistic works, while Islamic mathematical and astronomical knowledge contributed to scientific developments.

Technology Transfer

Crucial technologies spread across Eurasia during the Yuan era. Printing techniques moved westward, eventually influencing European printing development. Eastern advances in metallurgy, textile production, and nautical technology similarly diffused to other civilizations.

Agricultural technologies and crops also moved along trade routes established or secured by Mongol rule. Cotton cultivation expanded in China during this period, partly through knowledge and seeds brought from Central Asia and Persia. Similarly, improved irrigation techniques and water management systems spread across the Mongol-controlled territories.

Medical knowledge flowed in multiple directions, with Chinese pulse diagnosis techniques reaching Persian medical texts while Middle Eastern pharmacological knowledge influenced Chinese medicine. The Hui Hui Yaofang (Muslim Medicinal Recipes), compiled under Yuan patronage, preserved important information about medicinal substances and techniques from the Islamic world.

Military Organization and Technology

The Mongols transformed warfare not only through their conquests but also through lasting institutional and technological innovations:

Military Organization

The Yuan military combined traditional Mongol units with Chinese and other subject forces. The army was organized according to the decimal system, with units of ten, hundred, thousand, and ten thousand (tumen) soldiers. This organizational structure improved command efficiency and battlefield coordination.

The imperial guard (keshig) served not only as an elite military force but also as a training ground for future administrators and commanders. Young nobles from Mongol and allied families served in the guard, creating personal bonds of loyalty across the empire's ruling class while learning administrative and military skills.

Military colonies (tuntian) were established in strategic regions, combining agricultural production with military preparedness. This system, adapting earlier Chinese practices to Mongol requirements, helped maintain food supplies for garrisons while establishing a Mongol military presence throughout the empire.

Military Technology

The Yuan period saw significant developments in military technology, including

Improved composite bows with greater range and penetrating power

More effective siege engines, including counterweight trebuchets

Early firearms, including primitive hand cannons and explosive projectiles

Advances in naval warfare, with larger warships equipped with trebuchets and early cannon

Refined armor designs combining Mongol mobility requirements with greater protection

These technological advances shaped warfare not only in China but across Eurasia, as Mongol military methods were adopted by their former enemies and rivals. The military technologies developed or refined under the Yuan influenced warfare well into the early modern period.

Challenges and Decline

Despite its achievements, the Yuan Dynasty faced persistent challenges that ultimately led to its collapse:

Natural Disasters

The 14th century brought a series of natural calamities, including floods, droughts, and epidemics. The Yellow River changed course in 1344, causing devastating floods. These disasters stretched the government's capabilities and heightened popular discontent.

Climate historians have noted that the 14th century marked the beginning of the "Little Ice Age" in East Asia, with cooling temperatures affecting agricultural productivity. Shorter growing seasons and unpredictable rainfall patterns created food insecurity despite governmental efforts to maintain granary reserves.

The Black Death pandemic that devastated Europe also affected China during the late Yuan period, though with different timing and potentially different pathogens involved. Chinese historical records mention epidemic diseases killing significant portions of the population in several provinces during the 1330s-1350s, further straining the dynasty's resources.

Economic Problems

The Yuan's extensive use of paper money eventually led to inflation as later emperors printed currency without adequate backing. Agricultural production declined due to peasant unrest and natural disasters, creating food shortages and raising prices.

By the 1350s, the paper currency system had essentially collapsed. People reverted to using silver, copper coins, and barter for transactions, complicating tax collection and government finance. Commercial networks fragmented as the central government's control weakened, with local warlords and bandits disrupting previously secure trade routes.

The deteriorating economic situation particularly affected urban centers that had flourished during the dynasty's height. Cities like Hangzhou and Quanzhou, once centers of international commerce, experienced significant population decline as trade networks collapsed and residents fled ongoing conflicts.

Internal Strife

After Kublai's death in 1294, the Yuan court experienced increasing factionalism and succession disputes. Many later Yuan emperors were ineffective rulers who failed to address mounting problems. The dynasty's founder had established an elaborate governmental system, but his successors lacked the vision and capability to maintain it effectively.

Court factions often aligned with either traditional Mongol interests or those favoring greater adaptation to Chinese practices. This tension between maintaining Mongol identity and embracing Chinese imperial traditions created persistent political deadlocks that prevented effective responses to crises.

The average reign of Yuan emperors after Kublai was notably short—less than 7 years compared to much longer average reigns in stable Chinese dynasties. This rapid turnover in leadership created policy inconsistencies and allowed powerful officials and nobles to accumulate authority at the expense of central government control.

Popular Rebellions

By the mid-14th century, numerous rebellions erupted across China. The most significant was the Red Turban Rebellion, associated with the White Lotus Society, a Buddhist sectarian group. From these various rebellions emerged Zhu Yuanzhang, a former Buddhist monk who would eventually overthrow the Yuan and establish the Ming Dynasty in 1368.

The Red Turbans combined religious millenarianism with anti-Mongol sentiment, promising divine protection for their followers and the restoration of native Chinese rule. Their message resonated particularly strongly with peasants suffering from economic hardship and natural disasters, which were interpreted as signs of heaven's displeasure with Mongol governance.

The final years of the Yuan Dynasty saw China fragment into multiple competing regimes, with various rebel leaders controlling different regions while the Mongol court's authority contracted to the area around the capital. Zhu Yuanzhang gradually defeated rival rebel factions before turning north to challenge the remaining Yuan forces, forcing the last Yuan emperor to flee to Mongolia in 1368.

The Yuan Dynasty Beyond China

While this article focuses primarily on Yuan rule in China proper, it's important to recognize that the dynasty's influence extended far beyond China's traditional boundaries:

Korea and Japan

Korea's Goryeo Dynasty became a Mongol vassal state after decades of resistance. Korean royal princesses were sent as brides to the Mongol court, creating dynastic connections that influenced Korean politics for generations. The Mongols used Korea as a base for their unsuccessful invasion attempts against Japan in 1274 and 1281, events remembered in Japan as the "divine wind" (kamikaze) that saved the country from conquest.

Southeast Asia

Yuan influence extended into parts of mainland Southeast Asia, with military campaigns launched against Vietnam and Burma. While these regions weren't fully incorporated into the Yuan administrative system, they acknowledged Mongol suzerainty to varying degrees. The campaigns facilitated increased cultural and commercial contacts between China and Southeast Asian kingdoms.

Tibet and Central Asia

The relationship between the Yuan Dynasty and Tibet deserves special mention. Kublai Khan's embracing of Tibetan Buddhism created a "priest-patron" relationship with Tibetan religious leaders that established patterns of interaction continuing into the Qing Dynasty. Tibet was incorporated into the Yuan administrative system with a unique status, setting historical precedents for later Chinese claims to the region.

Central Asian territories from the Tarim Basin to the borders of Persia remained under Mongol control, though administered separately from China proper. These regions served as crucial links in the trade networks connecting China with western Eurasia and facilitated the movement of people, goods, and ideas that characterized the Yuan era.

Legacy and Historical Significance

The Yuan Dynasty's legacy extends far beyond its relatively brief 97-year rule:

Political Influence

Many Yuan administrative innovations, including the provincial system and certain governmental organizations, were adopted by the subsequent Ming and Qing dynasties. The concept of China as a multiethnic empire, rather than simply a Han Chinese state, became more firmly established.

The Ming Dynasty that succeeded the Yuan initially rejected many Mongol practices but gradually readopted elements of Yuan governance that had proven effective. Similarly, the Qing Dynasty—established by the Manchus, another non-Han people from beyond the Great Wall—studied Yuan precedents for methods of maintaining their distinct ethnic identity while ruling China.

The Yuan experience also influenced Chinese foreign policy for centuries. Subsequent dynasties maintained heightened awareness of developments on the northern frontier and invested heavily in border defenses and diplomatic management of steppe peoples—a direct response to the Yuan experience of foreign conquest.

Cultural Integration

The Yuan period accelerated the integration of northern and southern Chinese cultures while adding elements from Central Asia, Persia, and beyond. Many foods, musical instruments, architectural techniques, and artistic motifs that entered China during this period became permanent features of Chinese civilization.

Culinary innovations from the Yuan period that remain important in Chinese cuisine include various types of dairy products, certain noodle preparations, and the use of specific spices imported via Central Asian trade routes. The Muslim cuisine of northwestern China still reflects this historical fusion of culinary traditions.

Linguistic developments during the Yuan included the standardization of Mandarin as an administrative language and the introduction of numerous loan words from Mongolian, Persian, and Turkic languages. The development of vernacular literature during this period also had lasting impacts on Chinese literary traditions.

Global Awareness

Perhaps most significantly, the Yuan Dynasty placed China at the center of a global network of trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange. This connected the major civilizations of Eurasia more directly than ever before, setting the stage for the global interactions that would characterize later centuries.

European knowledge of and interest in China expanded dramatically following Yuan-era contacts. The search for direct maritime routes to China (bypassing Middle Eastern intermediaries) motivated the Age of Exploration, including Columbus's voyages. In this indirect but profound way, the Yuan Dynasty contributed to the emergence of the modern interconnected world.

The historical memory of the Yuan period also influenced later Chinese responses to foreign contacts and potential threats. The experience of being conquered yet ultimately absorbing the conquerors into Chinese civilization reinforced Chinese cultural confidence while simultaneously creating heightened sensitivity to foreign influences—a tension that continued to shape Chinese history through the modern era.

Archaeological Discoveries and Modern Research

Recent archaeological discoveries continue to enhance our understanding of the Yuan Dynasty:

Shipwrecks

Marine archaeology has recovered numerous shipwrecks from the Yuan period, providing tangible evidence of maritime trade networks. The Shinan wreck, discovered off the coast of Korea, contained Chinese ceramics and other goods destined for Japan, demonstrating the extent of East Asian maritime commerce during this era.

Architectural Remains

Excavations at sites like Shangdu (Xanadu), Kublai's summer capital, have revealed sophisticated urban planning combining Mongol and Chinese elements. The layout of imperial palaces, gardens, and ceremonial spaces shows how the Mongols adapted Chinese architectural traditions while maintaining elements reflecting their steppe heritage.

Material Culture

Archaeological finds, including ceramics, textiles, coins, and personal ornaments, provide insights into daily life during the Yuan. Scientific analysis of these artifacts has revealed production techniques, trade patterns, and changes in material culture that supplement textual records from the period.

The Yuan Dynasty represents a unique moment in Chinese history—a time when foreign conquest led not to cultural destruction but to unprecedented connections with the wider world. While the dynasty's rule was relatively brief and faced significant challenges, its impact on China and global history was profound and long-lasting.

From administrative innovations that would influence Chinese governance for centuries to the cultural and technological exchanges that connected East and West, the Yuan legacy continued long after the dynasty itself fell from power. In studying this remarkable period, we gain insights not only into China's past but also into the complex processes of cultural exchange and adaptation that have shaped our interconnected world.

Understanding the Yuan Dynasty helps us appreciate how civilizations respond to conquest and change—sometimes resisting, sometimes adapting, but always creating something new in the process. This resilience and creativity in the face of dramatic change remain one of the most enduring lessons of this fascinating chapter in world history.

The study of the Yuan Dynasty continues to evolve as new archaeological discoveries, interdisciplinary approaches, and comparative historical methods yield fresh insights into this pivotal period. Contemporary scholars increasingly recognize the Yuan era not as a mere interlude between native Chinese dynasties but as a transformative period that fundamentally reshaped China's relationship with the wider world and contributed to the emergence of the early modern global system.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚