The Theban Dynasty: Rise and Legacy of Ancient Egypt's Powerful Rulers

Discover the fascinating history of ancient Egypt's Theban Dynasty, whose powerful rulers transformed Egyptian civilization through military prowess, architectural marvels, and religious innovations. This comprehensive exploration reveals how kings and queens from Thebes reshaped history, created enduring monuments, and established cultural practices that continue to captivate historians and travelers alike.

HISTORYEMPIRES/HISTORYEDUCATION/KNOWLEDGE

Kim Shin

4/23/202515 min read

The Theban Dynasty represents one of ancient Egypt's most transformative periods, when rulers from the southern city of Thebes rose to reunify the country after periods of fragmentation. These kings and queens fundamentally altered Egypt's political landscape, military capabilities, and cultural development, leaving an enduring legacy that continues to fascinate historians and archaeologists today. This article explores the complex history, achievements, and significance of the Theban rulers who reshaped ancient Egyptian civilization.

Historical Context: The Path to Theban Power

The rise of Theban leadership emerged from Egypt's First Intermediate Period (circa 2181-2055 BCE), when central authority collapsed following the Old Kingdom. During this fragmented era, local governors established independent control over their regions. Thebes, situated in Upper Egypt along the Nile's eastern bank, gradually consolidated power under ambitious local leaders.

The political disintegration that characterized the First Intermediate Period stemmed from several factors: declining royal authority, climate change that reduced Nile flooding, and resulting agricultural failures that undermined the economic basis of centralized government. This created opportunities for regional centers like Herakleopolis in the north and Thebes in the south to assert greater independence.

The turning point came when Mentuhotep II (reigned approximately 2055-2004 BCE) successfully reunified Egypt, establishing what historians now call the Middle Kingdom. This achievement marked the beginning of significant Theban influence over Egyptian politics and culture that would extend, though not continuously, for centuries.

The Middle Kingdom Thebans

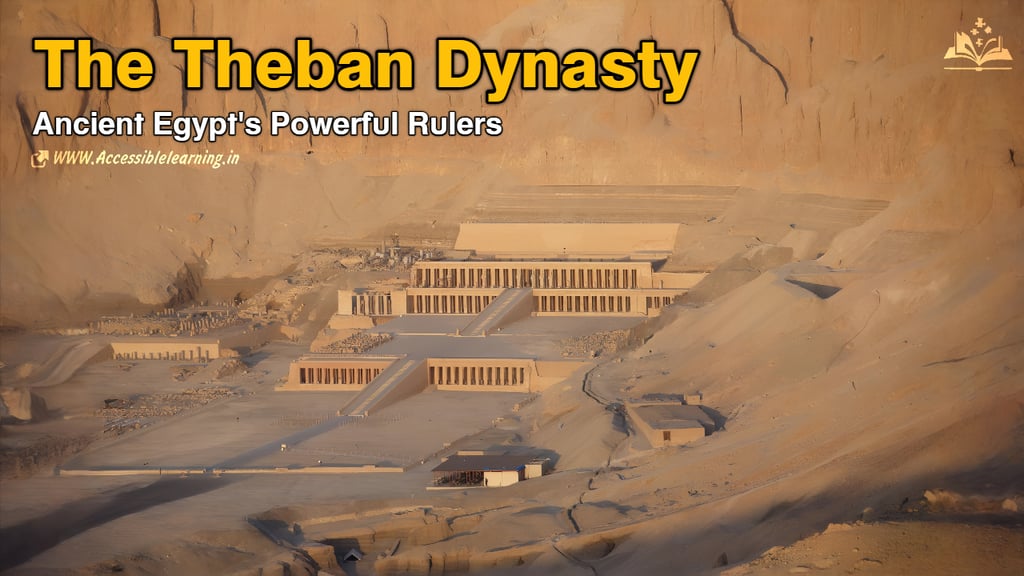

Mentuhotep II's reunification campaign required approximately 30 years of military campaigns against northern rivals, particularly the Herakleopolitan rulers of the 9th and 10th Dynasties. Ancient records suggest these conflicts were bitter and protracted, with decisive battles likely occurring near present-day Asyut. Upon securing control, he established his capital at Thebes and commissioned an innovative mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari, incorporating architectural elements that reflected both traditional Egyptian styles and new design concepts.

Mentuhotep II adopted titles and iconography deliberately reminiscent of Old Kingdom pharaohs, positioning himself as restorer of proper order (ma'at). Administrative records indicate he reorganized provincial governance, carefully balancing central authority with strategic appointments of local elites to maintain stability.

Under Mentuhotep's successors, Egypt experienced renewed stability and prosperity. The administration was restructured, trade networks expanded, and agricultural systems improved. Mentuhotep III and IV continued their predecessor's building programs, while archaeological evidence suggests they also undertook significant military expeditions to secure mining regions in the Eastern Desert and trade routes to the Red Sea.

The transition to the 12th Dynasty occurred when Amenemhat I, possibly a vizier of Mentuhotep IV, founded a new royal line. While technically relocating the administrative capital northward to Itjtawy near Faiyum, this dynasty maintained strong Theban connections. Kings continued supporting Theban temples and religious traditions, particularly those dedicated to the god Amun, whose significance grew substantially during this era.

Literature flourished during this period, producing classics like "The Tale of Sinuhe," "The Teachings of Amenemhat," and "The Eloquent Peasant," which reflect the period's cultural sophistication. These texts reveal complex theological ideas, ethical principles, and political theories that influenced Egyptian thought for centuries afterward.

The Second Intermediate Period and Theban Resistance

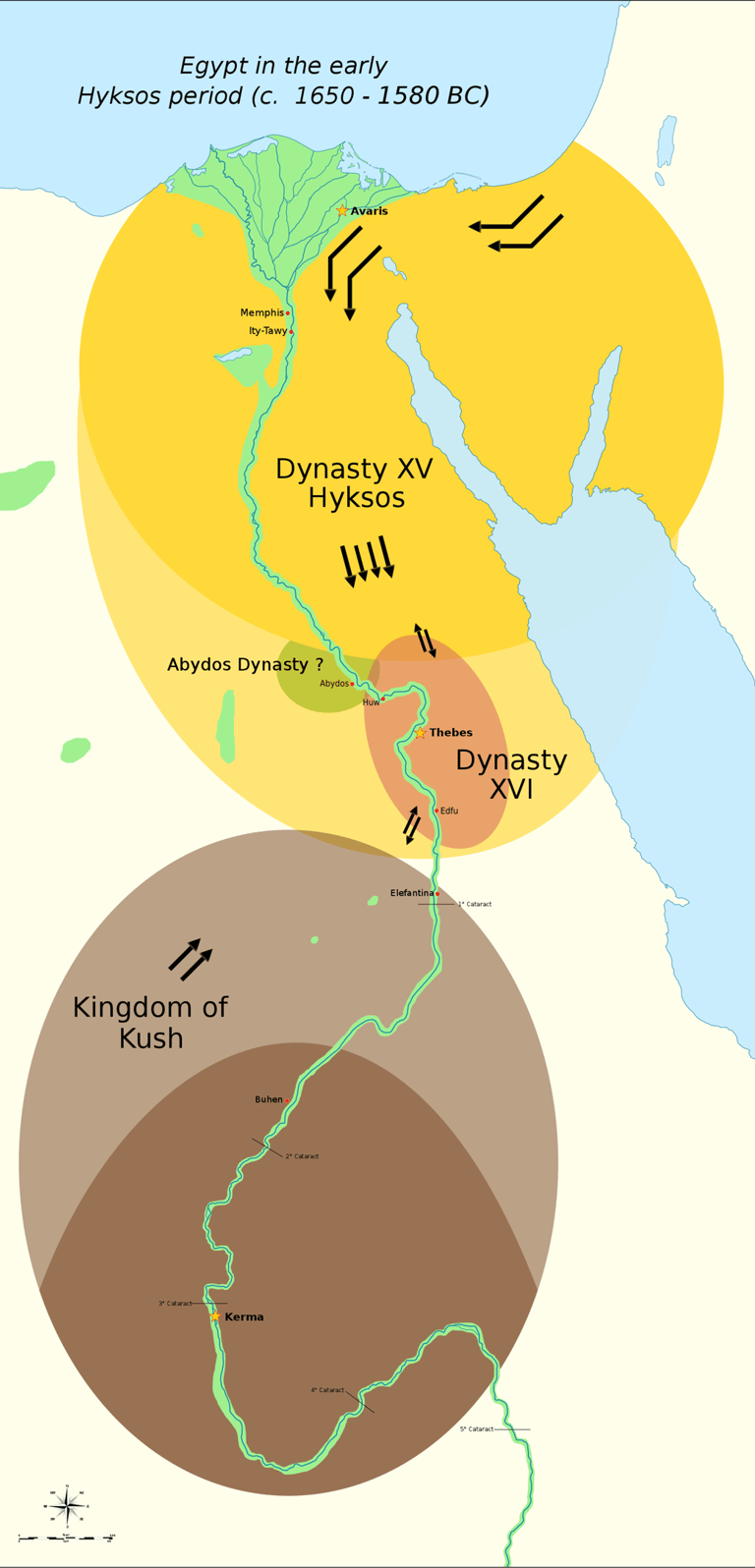

The Middle Kingdom's decline began during the 13th Dynasty, when shorter reigns and unclear succession patterns suggest internal political instability. Egypt gradually fragmented again, with power distributed among competing centers in the Delta, Middle Egypt, and the Theban region.

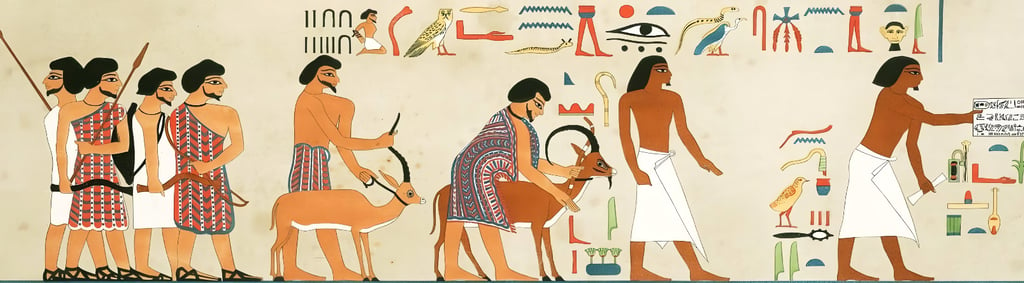

This fracturing created vulnerabilities that allowed the settlement and eventual dominance of western Asiatic peoples (commonly called Hyksos) in the northeastern Delta. Archaeological evidence from Tell el-Dab'a (ancient Avaris) confirms their growing influence through distinctive pottery, weapons, and burial practices. By approximately 1650 BCE, these foreign rulers had established the 15th Dynasty, controlling Lower Egypt while maintaining diplomatic and likely trade relationships with Theban rulers to the south.

The Theban 17th Dynasty maintained Egyptian traditions while gradually adopting some military technologies from their northern rivals, including composite bows, improved chariot designs, and bronze weaponry. Excavations at Thebes reveal fortification improvements and increased weapons production during this period, suggesting long-term preparation for conflict.

The resistance against Hyksos rule became explicit under Seqenenre Tao II, whose mummy displays violent head wounds that may indicate he died in combat. His successor, Kamose, as recorded on the Kamose Stela found at Karnak, launched campaigns northward, describing his motivation as both nationalistic and religious - portraying the conflict as necessary to restore proper religious observances and Egyptian sovereignty.

The New Kingdom Theban Renaissance

Ahmose I (circa 1550-1525 BCE), brother of Kamose, completed the expulsion of Hyksos rulers and pursued them into southern Canaan, as documented in the biographical inscription of a soldier named Ahmose son of Ebana. This military success launched the 18th Dynasty and the New Kingdom period, Egypt's imperial age.

Ahmose established administrative patterns that subsequent New Kingdom pharaohs would follow, rewarding military officers with land grants while carefully controlling their power through a balanced bureaucracy. His wife, Queen Ahmose-Nefertari, received the unprecedented title "God's Wife of Amun," reflecting both her personal influence and the growing political importance of Theban religious institutions.

The New Kingdom represents the apex of Theban influence. Under rulers like Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, and Amenhotep III, Egypt expanded into an empire stretching from Nubia to the Euphrates River. Thebes transformed into an imperial capital of unparalleled grandeur, with monumental construction projects including

The vast temple complex at Karnak, dedicated primarily to Amun-Ra, which expanded continually over centuries to become one of the ancient world's largest religious centers

The Luxor Temple, celebrating royal divinity and the Opet Festival, an annual celebration where the cult statue of Amun would travel from Karnak to Luxor, symbolically reuniting with the pharaoh

Elaborate mortuary temples on the west bank of the Nile, including Hatshepsut's terraced monument at Deir el-Bahari and the massive Ramesseum

The Valley of the Kings, housing royal tombs of extraordinary sophistication, with elaborately painted corridors and chambers documenting the pharaoh's journey through the afterlife

Hatshepsut's reign (circa 1479-1458 BCE) represents a particularly significant chapter in Theban history. Originally regent for her young stepson Thutmose III, she eventually claimed full pharaonic titles and iconography. Her extensive building program included not only her mortuary temple but also improvements to Karnak Temple and numerous shrines throughout Upper Egypt. Her famous trading expedition to Punt (possibly modern Somalia) brought exotic goods, including frankincense trees, gold, and animal specimens, demonstrating Egypt's extensive commercial networks.

Thutmose III, following Hatshepsut's death, established Egypt as the dominant military power in the Near East through seventeen documented campaigns into Syria-Palestine. His tactical brilliance, particularly displayed at the Battle of Megiddo (ca. 1457 BCE), earned him recognition as one of history's great military strategists. The wealth flowing into Egypt from tribute, trade, and war booty funded unprecedented construction projects and supported a sophisticated administrative system managed largely from Thebes.

The Amarna Period: Religious Revolution and Aftermath

The 18th Dynasty reached perhaps its most controversial period under Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten (circa 1353-1336 BCE) and attempted to replace traditional Egyptian religion with worship centered on the Aten (sun disk). This religious revolution included establishing a new capital at Akhetaten (modern Tell el-Amarna) and developing distinctive artistic styles that broke dramatically with traditional Egyptian conventions.

The Amarna period's impact on Thebes was profound. Temples to traditional deities faced reduced patronage; the priesthood of Amun experienced diminished influence and possibly active persecution. Archaeological evidence suggests some deliberate damage to Amun's name and imagery in Theban monuments. However, recent scholarship indicates that some level of traditional worship continued at Thebes even during the height of Atenism.

Following Akhenaten's death, a succession of rulers, including Tutankhamun, Ay, and Horemheb, gradually restored traditional practices. The famous "Restoration Stela" of Tutankhamun explicitly describes his efforts to repair neglected temples and reinstate proper religious observances. This period saw renewed attention to Theban cult centers, though archaeological evidence indicates the process was more gradual than often portrayed in official inscriptions.

Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, implemented significant administrative reforms addressing corruption that had apparently flourished during the Amarna period. His legal decrees, partially preserved at Karnak, established stricter regulations for officials and judges. His extensive construction at Karnak symbolically reaffirmed the traditional relationship between royal power and the Amun priesthood.

The Ramesside Period: Imperial Glory and Gradual Decline

The transition to the 19th Dynasty occurred when Ramesses I, a military officer appointed by Horemheb, founded a new royal line around 1292 BCE. His son Seti I and grandson Ramesses II conducted extensive building programs at Thebes while also establishing a new northern residence city at Pi-Ramesses in the eastern Delta, strategically positioned to address growing Hittite threats in the Levant.

Ramesses II's extraordinarily long reign (circa 1279-1213 BCE) saw massive construction throughout Egypt, but particularly at Thebes. His mortuary temple, the Ramesseum, included enormous statuary and extensive relief carvings documenting his military campaigns, particularly the Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites. Archaeological investigations reveal this complex included not only religious structures but also administrative buildings, storehouses, and workshops, functioning as a significant economic center.

The priesthood of Amun grew increasingly powerful during the Ramesside period. Donation records preserved on temple walls document extensive land grants that expanded the economic base of Theban religious institutions. High priests began including royal iconography in their tomb decorations, reflecting their elevated status. By the 20th Dynasty, these religious officials controlled vast resources and wielded significant political authority.

The later Ramesside period (1189-1077 BCE) saw Egypt facing increasing challenges: climate change affecting agricultural productivity, incursions by "Sea Peoples" documented in Medinet Habu temple reliefs, internal administrative corruption detailed in papyri from Deir el-Medina, and growing economic difficulties reflected in records of delayed worker payments and the first documented labor strikes in history. These factors gradually undermined centralized authority, setting the stage for the Third Intermediate Period's political fragmentation.

Theban Tomb Architecture and Artistic Developments

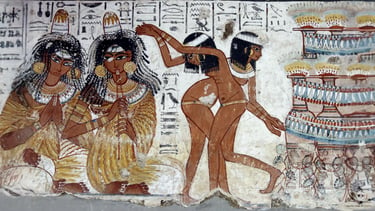

The mortuary landscape of Thebes offers unparalleled insights into artistic development across nearly a millennium. Early Theban tombs, like those of the 11th Dynasty nobles at el-Tarif, featured modest superstructures with rock-cut burial chambers. By the New Kingdom, elaborate painted tombs in the Theban necropolis showcased increasingly sophisticated artistic conventions.

Comparative analysis of tomb paintings reveals evolving techniques: early New Kingdom works often used primary colors in clearly defined scenes, while later examples demonstrated more nuanced color gradation and complex compositions. Technical studies have identified workshop patterns through shared artistic conventions, brush techniques, and pigment compositions, revealing how artistic knowledge was transmitted across generations.

The decorative programs of Theban tombs followed organized theological concepts. Entrance areas typically featured the deceased worshipping solar deities, representing transition between worlds. Central chambers displayed scenes of daily life, often idealized to represent eternal prosperity. Deeper chambers contained increasingly explicit funerary imagery relating to mummification, judgment scenes, and afterlife existence.

Royal tomb development in the Valley of the Kings reveals similar evolution. Early examples like Thutmose III's tomb (KV34) feature relatively simple plans with painted limestone walls. Later tombs, particularly from Horemheb onward, show increasingly complex floor plans, fully carved and decorated corridors, and elaborate astronomical ceilings. By the 20th Dynasty, tombs like that of Ramesses III (KV11) incorporated multiple chambers with specialized religious functions and extensive theological texts.

Religious Innovations and Theological Developments

The Theban dynasties profoundly shaped Egyptian religious development, particularly through elevating the god Amun from local deity to national patron. Eventually syncretized as Amun-Ra, this deity became central to Egyptian state theology. The priesthood at Karnak accumulated unprecedented wealth and influence, sometimes rivaling royal authority.

Theological texts from this period reflect increasingly sophisticated concepts. The "Hymn to Amun" preserved at Leiden Museum presents the deity as a transcendent, universal god beyond human comprehension while simultaneously being imminent and responsive to worshippers' needs. This theological evolution potentially influenced later monotheistic concepts that developed in the Mediterranean world.

Religious practices evolved to place greater emphasis on personal piety, particularly during the Ramesside period. Archaeological findings at Deir el-Medina include numerous small household shrines and votive offerings, suggesting direct relationships between individuals and deities. Prayer texts preserved on ostraca (limestone flakes) express concepts of divine judgment, forgiveness, and personal accountability that represent significant theological developments.

Royal mortuary cults underwent significant evolution during the Theban dynasties. Middle Kingdom practices emphasized continued provision for the deceased pharaoh's ka (life force) through offerings at mortuary temples directly connected to tomb structures. New Kingdom developments separated these functions, with public mortuary temples on the desert edge and concealed royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings, creating a dual-component system allowing both public commemoration and tomb security.

Social Structure and Daily Life in Theban Egypt

Archaeological evidence from settlement sites around Thebes, particularly the workmen's village at Deir el-Medina, provides exceptional documentation of social organization during the New Kingdom. Housing remains to show clear status differentiation, with larger homes for foremen and senior craftsmen contrasting with smaller dwellings for ordinary workers. Written records on ostraca and papyri detail everything from work assignments to personal disputes, market transactions, and religious observances.

The bureaucratic apparatus centered at Thebes created extensive documentation systems. Administrative texts reveal complex hierarchies of officials overseeing various aspects of governance: tax collection, agricultural production, construction projects, and religious foundation management. Literacy appears limited primarily to scribal professionals, who enjoyed elevated status as documented in texts like "The Satire of the Trades" that contrast scribal work favorably with manual occupations.

Women in Theban society occupied various roles depending on social status. Elite women managed household estates, participated in religious ceremonies, and sometimes held official titles related to temple service. Archaeological evidence from non-elite contexts shows women engaged in textile production, food processing, market activities, and possibly specialized crafts. Legal documents indicate women could own property, initiate divorce proceedings, and participate in commercial transactions, though with certain limitations compared to male counterparts.

Health conditions reflected both sophisticated medical knowledge and significant challenges. Mummy studies reveal evidence of parasitic infections, particularly schistosomiasis from Nile water contact. Dental examinations show significant abrasion from stone particles in bread, a dietary staple. Medical papyri from the period document hundreds of treatments for various conditions, combining empirical approaches with religious and magical elements.

Economic Foundations of Theban Power

The economic strength underlying Theban dynasties derived from multiple sources. Agricultural productivity centered on sophisticated irrigation systems expanding cultivable land beyond the natural Nile flood plain. Administrative texts document crop rotation practices, seed selection methods, and livestock management techniques that maximized production.

Nubian gold provided crucial wealth, supporting imperial expansion and monumental construction. Archaeological evidence from mining sites in the Eastern Desert and Nubia reveals extensive operations employing thousands of workers. Production estimates based on tomb paintings and inscriptional evidence suggest annual gold acquisition sufficient to produce thousands of deben (weight units), enabling Egypt's position as the ancient world's premier economic power during the New Kingdom.

International trade networks expanded dramatically during Theban imperial periods. Harbor facilities at Theban West (modern Qurna) supported river traffic connecting to Mediterranean ports. Imported goods documented in artistic representations and archaeological findings include cedar from Lebanon, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, silver from Anatolia, and ebony from sub-Saharan Africa. Trade relationships required sophisticated diplomatic systems, including royal correspondence preserved in archives like those found at Amarna.

Temple economies constituted a significant economic sector. Donation texts inscribed at Karnak indicate the temple controlled hundreds of agricultural estates, workshops, and other productive enterprises. These institutions functioned as economic redistribution centers, employing numerous specialists: priests, craftsmen, agricultural workers, and administrative personnel. Recent archaeological work has revealed extensive storage facilities and production areas associated with temple complexes.

Technological and Scientific Achievements

Technological innovation accelerated during Theban dynastic periods. Metallurgical advances included more sophisticated bronze-working techniques and eventually early iron production during the late New Kingdom. Glass manufacturing, likely adapted from Mesopotamian origins, developed into a significant Egyptian industry producing luxury vessels and decorative elements documented in archaeological contexts at Malkata and other Theban sites.

Architectural knowledge advanced significantly, enabling construction of increasingly complex monuments. Engineering developments included improved methods for quarrying, transporting, and precisely placing massive stone blocks. The astronomical orientation of structures like Karnak Temple demonstrates sophisticated observational techniques allowing alignment with celestial phenomena like solstices and specific star positions.

Mathematical understanding, preserved in papyri like the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, shows Egyptian capabilities in geometry, algebra, and practical calculation methods. These mathematical principles found practical application in monument construction, field measurement following Nile floods, and administrative record-keeping. Calendar systems developed during this period achieved remarkable accuracy through astronomical observations recorded in ceiling decorations and dedicated instruments.

Medical knowledge expanded through empirical observation documented in texts like the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus and Ebers Medical Papyrus. These works describe hundreds of conditions with corresponding treatments, sometimes showing remarkable effectiveness despite limitations in theoretical understanding. Archaeological evidence from mummies reveals successful surgical interventions, including trepanation and fracture setting with subsequent healing.

Military Organization and Imperial Administration

The military organization that enabled Theban imperial expansion underwent significant evolution from the Middle Kingdom through the New Kingdom periods. Early forces consisted primarily of conscripted infantry supplemented by Nubian mercenary archers. The Hyksos period introduced transformative technologies, particularly the horse-drawn chariot that became central to Egyptian battle tactics during the New Kingdom.

By the 18th Dynasty, the Egyptian military had developed specialized divisions, including chariotry units, infantry with standardized equipment, archer contingents, and naval forces operating on both the Nile and Mediterranean. Administrative texts reveal sophisticated logistics systems supporting these forces with weapons production facilities, training centers, and supply networks extending throughout Egyptian territory.

Imperial administration during the Theban imperial period developed innovative governance approaches for conquered territories. Unlike some ancient empires that imposed direct rule, New Kingdom Egypt generally allowed local leaders to maintain authority under Egyptian supervision. This system required local princes to send their heirs to Egypt for education, ensuring cultural integration of future rulers. Regular tribute payments and military obligations maintained Egyptian dominance while minimizing administrative costs.

Frontier regions received more direct control, with fortress systems protecting boundaries and trade routes. Archaeological investigations in Nubia have uncovered extensive fortifications at sites like Buhen and Semna, demonstrating substantial investment in securing southern territories where gold resources were particularly valuable. Similar defensive systems in the northeastern Delta and along the "Ways of Horus" route into Canaan protected against Asiatic threats.

Decline and Transformation

The centralized authority of New Kingdom Egypt gradually weakened during the later Ramesside period. Economic challenges, administrative corruption, foreign incursions, and internal power struggles contributed to fragmentation. By the Third Intermediate Period (circa 1069-664 BCE), Egypt was divided into competing centers of power.

Thebes maintained semi-independence under the authority of the High Priests of Amun, sometimes functioning as a theocratic state within Egypt. The genealogy of these priest-rulers, reconstructed from tomb inscriptions and donation records, reveals complex family networks maintaining control across generations. Archaeological evidence suggests continued construction activities and artistic production, though at a reduced scale compared to imperial periods.

The role of Kushite rulers from Nubia (25th Dynasty, circa 747-656 BCE) represents an important chapter in late Theban history. These kings presented themselves as restorers of traditional Egyptian religion and practices, investing significantly in Theban temple renovations and religious ceremonies. Their artistic productions deliberately referenced Old and Middle Kingdom styles, demonstrating sophisticated understanding of Egyptian cultural history.

Assyrian invasions in the mid-7th century BCE brought temporary devastation to Thebes, graphically described in biblical and Assyrian accounts. Archaeological evidence confirms destruction layers at several Theban sites dating to this period. However, subsequent Saite rulers (26th Dynasty) undertook restoration projects, though political emphasis shifted decisively to northern centers.

During the Late Period and subsequent Ptolemaic rule, Thebes retained religious significance while gradually transforming into a provincial center. Temple construction continued, notably at Karnak and Luxor, now emphasizing Egyptian traditions in opposition to foreign cultural influences. Native rebellions against Persian and later Ptolemaic rule frequently originated in the Theban region, reflecting continuing regional identity and resistance to external control.

Archaeological Rediscovery and Modern Understanding

Modern understanding of Theban dynasties emerged gradually through archaeological exploration beginning in the early 19th century. Early European travelers like Giovanni Belzoni conducted initial excavations in the Valley of the Kings, discovering significant tombs, including those of Seti I and Ramesses IV. These early efforts, while recovering impressive artifacts, often lacked systematic documentation.

Scientific archaeology at Thebes developed through the work of pioneers like Flinders Petrie, whose stratigraphic methods revolutionized understanding of chronological relationships. The discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb by Howard Carter in 1922 brought unprecedented public attention to Theban archaeology while also advancing techniques for artifact conservation and documentation.

Contemporary archaeological projects employ sophisticated technologies like ground-penetrating radar, digital photogrammetry, and multispectral imaging to examine Theban monuments. These approaches have revealed previously undetected structures, clarified architectural development sequences, and recovered faded inscriptions invisible to the naked eye. Bioarchaeological studies of human remains provide insights into health conditions, dietary patterns, and population movements throughout the Theban periods.

Epigraphic projects systematically documenting Theban inscriptions and relief carvings have revolutionized scholarly understanding of historical narratives, religious concepts, and administrative systems. Digital humanities approaches now allow integration of textual, archaeological, and art historical evidence, creating more comprehensive understandings of Theban civilization in its multiple dimensions.

Legacy and Cultural Influence

The architectural achievements of Theban dynasties continue influencing modern aesthetics and design principles. The proportional systems and monumental scale of structures like Karnak Temple inspired neoclassical architecture in 19th-century Europe and America. Egyptian motifs derived primarily from Theban monuments became incorporated into decorative arts during multiple "Egyptomania" periods following major archaeological discoveries.

Literary traditions developed during Theban dynasties, particularly religious texts like the Book of the Dead and literary works such as the "Tale of Two Brothers," influenced subsequent Mediterranean civilizations. Scholars have identified potential connections between Egyptian theological concepts developed at Thebes and later religious traditions, including possible influences on early monotheistic ideas.

The rediscovery of Theban monuments significantly shaped the development of modern Egyptology as an academic discipline. The extensive preservation of texts, artistic representations, and archaeological remains from this region provides unparalleled resources for understanding ancient Egyptian civilization. Contemporary cultural heritage management challenges at Thebes, including tourism impacts, climate change threats, and conservation needs, represent ongoing concerns for preserving this exceptional historical legacy.

The Theban dynasties represent critical turning points in Egyptian history—periods when strong leadership emerged from southern Egypt to restore unity, expand territorial control, and revitalize cultural expression. Their architectural achievements remain among humanity's most impressive monuments, while their religious innovations profoundly influenced subsequent theological development throughout ancient Egypt and potentially beyond.

Modern research continues revealing new dimensions of Theban history through archaeological discoveries, improved translation capabilities, and interdisciplinary methodologies. As scholars piece together this complex historical narrative, we gain a deeper appreciation for how these ambitious rulers and their sophisticated administrative systems shaped one of humanity's most enduring civilizations.

The story of the Theban dynasties ultimately reveals the remarkable achievements possible through stable governance, religious cohesion, and cultural confidence, while also demonstrating how these systems faced challenges from internal corruption, resource limitations, and external pressures. In studying this civilization, we gain valuable perspective on universal aspects of human societal development, political organization, and cultural expression that continue resonating with contemporary concerns.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚