The Seleucid Empire: Rise, Dominance, and Legacy of an Ancient Superpower

Discover the forgotten legacy of the Seleucid Empire, the vast Hellenistic kingdom that ruled from the Mediterranean to India for nearly three centuries. Learn how these innovative rulers created a sophisticated administrative system, fostered unprecedented cultural exchange, and left an enduring impact on world history that resonates to this day.

EMPIRES/HISTORYHISTORYEDUCATION/KNOWLEDGE

Keshav Jha

3/26/202512 min read

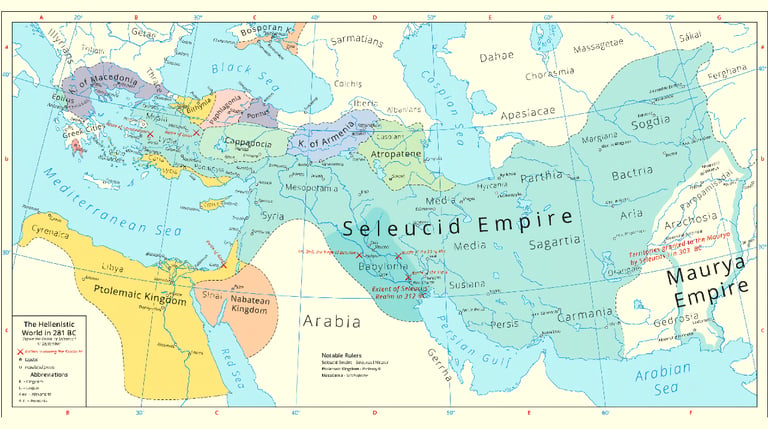

The Seleucid Empire stands as one of history's most significant yet often overlooked imperial powers. Emerging from the fractured remnants of Alexander the Great's conquests, this Hellenistic kingdom stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the borders of India at its height. For nearly three centuries (312–63 BCE), the Seleucids controlled vast territories, diverse populations, and immense wealth, leaving an indelible mark on the ancient world through their innovative governance, cultural exchanges, and military prowess.

Origins & Formation

The death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE left a power vacuum that triggered intense competition among his generals, known as the Diadochi. Seleucus I Nicator, a trusted commander and former bodyguard of Alexander, emerged as one of the victors in this complex struggle. After initial setbacks, Seleucus secured control of Babylon in 312 BCE—the date traditionally marking the foundation of the Seleucid Empire.

Seleucus demonstrated remarkable strategic acumen by capitalizing on the instability following Alexander's death. Through a combination of military campaigns, shrewd diplomacy, and timely alliances, he gradually expanded his territory eastward into Persia and westward toward the Mediterranean. His decisive victory at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE consolidated his position as one of the most powerful successors to Alexander's legacy.

The Early Years of Seleucus I Nicator

Before establishing his empire, Seleucus served as the commander of the elite Silver Shields infantry unit and later as chiliarch (grand vizier) in Alexander's administration. Following Alexander's death, Seleucus initially received the satrapy of Babylon in the Partition of Babylon but was forced to flee when another general, Antigonus Monophthalmus, seized control of large portions of the eastern territories.

Seleucus found refuge with Ptolemy I in Egypt before returning to Babylon in 312 BCE with a small force. His ability to reclaim Babylon with minimal military resources demonstrated his diplomatic skill and popularity among local populations. This event, recorded as the beginning of the Seleucid Era, served as the starting point for the calendar system used throughout the empire for centuries.

Territorial Expanse and Administration

At its zenith under Antiochus III (the Great), the Seleucid Empire encompassed modern-day Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, parts of Turkey, Armenia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and portions of Central Asia. This vast domain presented unprecedented administrative challenges, which the Seleucids addressed through a sophisticated bureaucratic system.

The empire was divided into provinces called satrapies, an administrative structure inherited from the Persian Empire. However, the Seleucids introduced important innovations, including:

A network of Greek-style cities (poleis) strategically founded throughout the empire

A centralized taxation system that efficiently collected revenue from diverse regions

Royal roads and communication networks that facilitated trade and military movements

A balance between local autonomy and central authority that helped maintain stability

This administrative framework allowed the Seleucids to govern an extraordinarily diverse population encompassing numerous ethnic groups, religions, and languages.

Administrative Innovations

The Seleucid administrative system featured several layers of governance:

The king stood at the apex, holding absolute authority and serving as the empire's chief judge, military commander, and religious leader

The royal court included family members, trusted advisors, and specialized officials who assisted in governance

Regional governors (strategoi) administered satrapies with considerable autonomy while remaining accountable to the central authority

City administrators managed local affairs in the numerous Greek-style cities founded throughout the empire

Village headmen oversaw rural communities, forming the lowest tier of imperial administration

This hierarchical structure enabled efficient governance while allowing for regional variations that accommodated local customs and traditions. The Seleucids maintained extensive archives and employed numerous scribes to record administrative details, demonstrating a sophisticated bureaucratic approach to imperial management.

Economic Prosperity and Trade

The Seleucid Empire functioned as a critical economic hub connecting East and West. Its strategic location astride major trade routes, including the Silk Road, facilitated commercial exchanges between China, India, Arabia, and the Mediterranean world.

The Seleucid economy benefited from:

Control of key trade routes and ports

Rich agricultural lands in Mesopotamia and Syria

Abundant natural resources, including gold, silver, timber, and precious stones

Innovative coinage system that standardized economic transactions

Royal monopolies on certain goods and careful management of taxation provided substantial revenue for the state treasury, funding ambitious building projects, military campaigns, and imperial administration.

Currency and Monetary System

The Seleucid monetary system was remarkably sophisticated. The empire minted coins in gold, silver, and bronze, with standardized weights and values that facilitated commerce throughout their territories. Major mints operated in cities such as Antioch, Seleucia on the Tigris, Ecbatana, and Bactria, each producing coins with distinctive markings.

Seleucid coinage typically featured the portrait of the reigning king on the obverse and Apollo, the dynasty's patron deity, seated on the omphalos (navel stone) on the reverse. This iconography reinforced royal authority and divine legitimacy while providing a recognizable medium of exchange across the empire's diverse regions.

The introduction of a standardized currency system reduced transaction costs for merchants and enabled more efficient tax collection. This monetary innovation represented one of the Seleucid Empire's most significant economic contributions.

Urban Development and City Founding

The Seleucids embarked on an ambitious program of city foundation, establishing dozens of new urban centers throughout their territories. These cities served multiple purposes:

Military colonies to maintain control over conquered territories

Administrative centers from which to govern surrounding regions

Cultural outposts that spread Hellenistic civilization

Economic hubs that stimulated trade and manufacturing

Major Seleucid foundations included:

Seleucia on the Tigris: A massive metropolis that may have housed up to 600,000 residents at its peak, serving as the eastern capital of the empire

Antioch on the Orontes: The western capital and one of the ancient world's greatest cities, rivaling Alexandria and Rome in significance

Apamea: A major military center hosting the empire's main cavalry training facilities and elephant stables

Dura-Europos: A frontier city on the Euphrates that exemplified the blending of Greek and Near Eastern cultural elements

Each city was typically designed according to the Hippodamian grid plan, with straight streets intersecting at right angles, creating organized urban spaces centered around an agora (marketplace). Public buildings such as theaters, gymnasiums, and temples provided spaces for cultural and civic activities, while city walls offered protection from external threats.

Cultural Fusion and Hellenization

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the Seleucid Empire lies in its role as a cultural melting pot. The Seleucid rulers actively promoted Hellenization—the spread of Greek culture, language, and institutions—throughout their territories. This policy manifested in several ways:

The foundation of new Greek-style cities, complete with traditional institutions like gymnasiums, theaters, and agoras

Patronage of Greek art, literature, and philosophy

Establishment of Greek as the administrative language alongside local tongues

Introduction of Greek architectural styles and urban planning principles

However, this was not a one-directional process. The Seleucids also absorbed and adapted local traditions, creating a unique syncretic culture. They maintained respect for local religious practices, often identifying Greek deities with local gods, and incorporated elements of Persian court ceremonial into their governance.

This cultural fusion produced remarkable achievements in art, science, and literature. The famous astronomical observations at Babylon continued under Seleucid patronage, and Greek scientific knowledge blended with Mesopotamian and Persian traditions.

Intellectual and Artistic Achievements

The Seleucid era witnessed significant intellectual and artistic developments:

The astronomical diaries kept by Babylonian priests continued under Seleucid patronage, compiling some of the ancient world's most accurate astronomical observations

Mathematical and scientific knowledge flourished as Greek and Mesopotamian traditions cross-fertilized

Literary production thrived, with poets and historians working in both Greek and local languages

Artistic styles merged Greek aesthetic principles with local traditions, creating distinctive regional variations in sculpture, painting, and decorative arts

The library at Antioch, though less famous than its Alexandrian counterpart, housed thousands of scrolls and attracted scholars from throughout the Hellenistic world. The Seleucids supported intellectual inquiry as a matter of policy, recognizing its prestige value and practical applications.

Military Power and Warfare

The Seleucid military combined Macedonian tactical traditions with local military practices. At its core stood the phalanx—a formation of heavily armored infantry wielding long spears (sarissas)—supported by cavalry units, war elephants, and specialized troops.

The Seleucid army reflected the empire's multicultural nature, incorporating:

Macedonian and Greek settlers who formed the elite heavy infantry

Iranian and Central Asian cavalry providing mobility and range

War elephants obtained from India for shock value

Local infantry levies offering numerical strength

This diverse military force allowed the Seleucids to project power across vast distances, though maintaining such a large standing army placed significant strain on imperial finances.

Military Organization and Innovation

The Seleucid military was organized around several key components:

The Agema: The royal guard unit, comprising elite infantry and cavalry directly loyal to the king

The phalanx: The main infantry formation, typically 16 men deep, armed with 5-7-meter sarissas (pikes)

Cataphracts: Heavily armored cavalry equipped with kontos (long lances) and providing shock capability

Light cavalry: Mobile horse archers and javelin-throwers, often recruited from Iranian populations

Elephant corps: A specialized branch responsible for training and deploying war elephants, which the Seleucids used more extensively than any other Hellenistic kingdom

Siege engineers: Technical specialists who designed and operated sophisticated siege equipment

The Seleucids introduced several innovations in military technology and tactics:

Scythed chariots: Modified war chariots with blades attached to the axles and wheels

Improved elephant armor and towers that could hold multiple soldiers

Advanced siege equipment, including larger and more powerful catapults

Mixed-arms tactics that combined the strengths of different troop types

The famous military parade at Daphne organized by Antiochus IV in 166 BCE showcased the empire's military might, featuring 40,000 infantry, thousands of cavalry, scythed chariots, and 36 war elephants in full battle array.

Religious Policies and Conflicts

The Seleucid approach to religion was generally pragmatic and tolerant. They respected local religious traditions and often portrayed themselves as protectors of various cults. In Babylon, for instance, Seleucid kings participated in traditional Mesopotamian rituals and supported the rebuilding of temples.

However, this tolerance had limits, particularly when religious practices threatened imperial authority or revenue. The most notorious example occurred under Antiochus IV Epiphanes, whose attempts to Hellenize Judea and his desecration of the Jerusalem Temple in 167 BCE provoked the Maccabean Revolt—a Jewish uprising that eventually led to the establishment of the independent Hasmonean kingdom.

This conflict, immortalized in the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah, represents one of the few instances where Seleucid religious policies generated significant resistance.

Divine Kingship and Royal Cult

Seleucid rulers adopted aspects of both Macedonian and Near Eastern traditions of kingship, gradually developing a concept of divine monarchy. While early Seleucid kings like Seleucus I claimed divine descent (from Apollo), later rulers such as Antiochus IV Epiphanes ("God Manifest") made more explicit claims to divinity.

The royal cult became an important aspect of Seleucid governance, providing a religious foundation for political authority. Temples dedicated to ruler worship were established in major cities, and festivals celebrating the deified kings became regular features of civic life. This practice helped integrate diverse populations by providing a common focus of loyalty transcending ethnic and cultural divisions.

Major Rulers and Their Achievements

Seleucus I Nicator (r. 312-281 BCE)

The dynasty's founder established the empire's fundamental structures and expanded its territories from Syria to the borders of India. He founded numerous cities, including Seleucia on the Tigris and Antioch on the Orontes, which became the empire's eastern and western capitals, respectively. Seleucus was assassinated in 281 BCE while attempting to conquer Macedonia.

Antiochus I Soter (r. 281-261 BCE)

The son of Seleucus I consolidated the empire's eastern territories and successfully repelled Celtic invaders (Galatians) who had crossed into Asia Minor. Known for his cultural patronage, he supported the temple of Apollo at Didyma and commissioned the famous Cylinder of Antiochus, which documented his restoration of the Esagila temple in Babylon.

Antiochus III the Great (r. 223–187 BCE)

Perhaps the most accomplished Seleucid ruler, Antiochus III, restored the empire to its greatest territorial extent through his "anabasis" (eastern campaign) that reached as far as India. He reasserted Seleucid authority in Asia Minor and briefly held parts of Greece. However, his expansion westward brought him into conflict with Rome, resulting in the decisive Battle of Magnesia (190 BCE) that marked the beginning of Seleucid decline.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175-164 BCE)

A complex and controversial ruler, Antiochus IV pursued aggressive Hellenization policies and intervened directly in the Jerusalem Temple cult, precipitating the Maccabean Revolt. He conducted successful campaigns against Egypt (though Roman intervention prevented complete conquest) and organized the grand procession at Daphne to demonstrate Seleucid power. His eastern campaigns against the Parthians ended with his unexpected death in 164 BCE.

Foreign Relations and Diplomacy

The Seleucid Empire maintained complex diplomatic relationships with neighboring powers.

Egypt (Ptolemaic Kingdom): A perpetual rival, with whom the Seleucids fought six major "Syrian Wars" for control of valuable territories in the Levant

Macedonia: Sometimes an ally, sometimes a competitor, connected by dynastic marriages and cultural ties

Rome: Initially distant but increasingly interventionist, eventually contributing significantly to Seleucid decline

Bactria: A breakaway kingdom that maintained cultural connections with the Seleucid homeland

Parthia: The emerging power in Iran that gradually eroded Seleucid eastern territories

India (Mauryan Empire): Connected by diplomacy and trade, with embassies exchanged between the courts

Seleucid diplomacy employed various tools, including:

Dynastic marriages that created alliances with neighboring kingdoms

Formal treaties specifying territorial boundaries and commercial rights

Exchange of valuable gifts and cultural artifacts

Royal hostages (typically princes) sent to foreign courts as guarantees of good behavior

Trade agreements that regulated commercial interactions

Decline and Legacy

Multiple factors contributed to the Seleucid Empire's gradual decline:

Territorial losses to the rising Parthian Empire in the east

Roman interference and military defeats in the west

Internal dynastic conflicts that weakened central authority

Economic strain from constant warfare

Rebellions in various provinces

By the mid-2nd century BCE, the Seleucids had lost control of their eastern provinces to the Parthians. Their western territories gradually fell under Roman influence, culminating in Pompey's annexation of Syria in 63 BCE, which marked the formal end of the empire.

The Final Century: Fragmentation and Civil Wars

The period from 150 to 63 BCE witnessed an accelerating decline, characterized by:

Dynastic civil wars that sometimes saw multiple claimants simultaneously controlling different portions of the remaining territory

Increasing autonomy of cities and regions as central authority weakened

Roman political manipulation, particularly after the Battle of Magnesia

Armenian expansion under Tigranes the Great, who briefly controlled much of the remaining Seleucid territory

Economic deterioration resulting from constant warfare and territorial losses

The final Seleucid king, Philip II, was deposed when Pompey incorporated Syria into the Roman provincial system in 63 BCE, bringing the once-mighty empire to an inglorious end.

Despite its dissolution, the Seleucid legacy endured. Their cities continued to serve as centers of Hellenistic culture well into the Roman period. The administrative systems they developed influenced subsequent empires. Most importantly, the cultural synthesis they fostered—blending Greek, Persian, Mesopotamian, and other traditions—created a cosmopolitan civilization that shaped the development of the entire region.

Archaeological Evidence and Material Culture

Archaeological excavations have revealed much about Seleucid material culture:

The impressive ruins of Seleucia on the Tigris demonstrate sophisticated urban planning

Excavations at Ai Khanoum in Afghanistan reveal how Greek architectural forms were adapted to Central Asian conditions

Temple complexes at Dura-Europos show the fusion of Greek and Near Eastern religious practices

Coin hoards provide evidence of economic networks and royal iconography

Inscriptions in multiple languages document administrative practices and royal proclamations

Recent archaeological work has expanded our understanding of rural settlements and provincial life beyond the major urban centers, revealing the diversity of experience within the empire's borders.

Historical Sources

Our knowledge of the Seleucid Empire comes from various sources:

Greco-Roman histories: Works by Polybius, Livy, Appian, and others provide narrative accounts, though often from an external perspective

Babylonian chronicles: Cuneiform texts that record significant events and astronomical observations

Epigraphic evidence: Royal inscriptions, civic decrees, and administrative documents preserved on stone and other durable materials

Numismatic evidence: Coins that provide chronological frameworks and iconographic information

Archaeological findings: Material remains that offer insights into daily life, trade networks, and cultural practices

Jewish sources: Books of Maccabees and the writings of Josephus that document Seleucid policy in Judea

The fragmentary nature of these sources presents challenges for modern historians, but continuing archaeological discoveries and improved methodologies are steadily enhancing our understanding of this complex empire.

Modern Significance and Study

The Seleucid Empire has received renewed scholarly attention in recent decades.

Numismatic studies have revealed new information about economic patterns and royal ideology

Archaeological excavations at sites like Ai Khanoum have transformed our understanding of Hellenistic cultural influence in Central Asia

Digital humanities approaches have enabled more sophisticated analysis of administrative networks and settlement patterns

Interdisciplinary research combining textual and archaeological evidence has produced more nuanced interpretations of Seleucid governance

This historical period offers valuable insights for contemporary discussions about:

Cultural globalization and the interaction of different civilizational traditions

Imperial governance of multicultural populations

The balance between central authority and local autonomy

Economic integration across diverse regions

Religious pluralism and identity politics

The Seleucid Empire represents a remarkable chapter in ancient history—a vast, multicultural state that maintained stability and prosperity across a culturally diverse domain for nearly three centuries. Its sophisticated governance, economic innovations, and cultural policies facilitated unprecedented exchanges between East and West, leaving an indelible mark on the ancient world.

Though eventually overshadowed by Rome and Parthia, the Seleucid legacy lived on in the Hellenized cities they founded, the administrative structures they developed, and the cultural fusion they fostered. Modern scholars increasingly recognize the Seleucids not merely as inheritors of Alexander's conquests but as innovative state-builders who created one of the ancient world's most sophisticated imperial systems.

In studying the Seleucid Empire, we gain valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities of governing diverse populations, the dynamics of cultural exchange, and the delicate balance between central authority and local autonomy—issues that remain relevant in our interconnected world today.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚