The Sassanid Empire: Legacy of Ancient Persia's Golden Age

Discover the remarkable civilization that rivaled Rome and shaped the medieval world. This comprehensive exploration reveals how the Sassanid Empire (224-651 CE) created enduring political systems, artistic traditions, and cultural achievements that continue to influence Middle Eastern and world history today.

HISTORYEDUCATION/KNOWLEDGEEMPIRES/HISTORY

Kim Shin

5/7/202513 min read

The Sassanid Empire (224-651 CE) stands as one of history's most influential yet often overlooked civilizations. As the last great Persian empire before the Islamic conquest, the Sassanids created a sophisticated society that rivaled Rome in splendor and power. For over four centuries, they ruled a vast territory stretching from the Euphrates River to the Indus Valley, establishing a cultural and political legacy that would influence the Middle East, Central Asia, and beyond for centuries to come. This "Second Persian Empire" represents a crucial chapter in world history—a time when Persian civilization reached new heights of achievement and complexity.

Origins and Rise to Power

The Sassanid dynasty emerged from the ashes of the Parthian Empire, which had ruled Persia for nearly five centuries. The founder, Ardashir I, began as a local ruler in the province of Pars (modern-day Fars province in Iran). In 224 CE, after defeating the last Parthian king, Artabanus V, in the Battle of Hormozdgan, Ardashir declared himself "Shahanshah"—King" of Kings—establishing what would become one of the most formidable empires of late antiquity.

Ardashir's rise wasn't merely a change in leadership; it represented a conscious revival of ancient Persian traditions and Zoroastrian religious identity. The very name "Sassanid" derives from Sasan, a high priest of the temple of Anahita and Ardashir's ancestor, highlighting the dynasty's religious foundations.

The Sassanid revolutionary program involved a deliberate connection to the Achaemenid Empire of Cyrus and Darius—portraying themselves as restorers of Persian greatness after centuries of Hellenistic influence under the Seleucids and Parthians. Ardashir commissioned rock reliefs at Naqsh-e Rustam near Persepolis, deliberately placing his victory monuments alongside those of Achaemenid kings, symbolically linking his dynasty to Persia's golden age.

Political Structure and Administration

The Sassanid Empire developed a remarkably centralized and efficient administrative system that would later influence Islamic and medieval European governance:

Divine Kingship: The Shahanshah held absolute power as the divinely appointed ruler, with elaborate court protocols emphasizing his sacred status. The king wore a distinctive crenelated crown, unique to each ruler, and was referred to as "Bay" (divine).

Hierarchical Nobility: Society was organized into a strict hierarchy with four main classes: priests (magi), warriors (artēštārān), scribes/bureaucrats (dibīrān), and commoners (vastryōšān and hutuxšān). Social mobility was limited, with positions typically inherited.

Provincial Administration: The empire was divided into provinces (satrapies) governed by appointed officials who answered directly to the king. Major provinces were often entrusted to royal family members, while frontier regions were administered by military governors (marzbans).

Bureaucratic Efficiency: A sophisticated taxation system and census ensured the empire's wealth and military power. Taxes were collected in both coin and kind, with agricultural production carefully monitored.

Royal Court: The court included specific positions such as the Vuzorg Framadar (Prime Minister), Eran-Spahbod (Commander-in-Chief), and Mobed Mobedan (Chief Priest), creating a sophisticated bureaucracy.

Unlike their Roman counterparts, Sassanid monarchs cultivated an aura of divine mystery, rarely appearing in public and conducting court affairs from behind curtains. This tradition of royal seclusion would later influence Byzantine and Islamic court practices.

The Sassanids also instituted a unique system of dynastic chronicles—the Khwaday-Namag (Book of Lords)—recording official histories of the kings and their deeds. Though the original texts have been lost, translations and adaptations survived to influence later Persian historical works like Ferdowsi's Shahnameh.

Military Might and Roman Rivalry

Perhaps the most defining aspect of Sassanid history was their ongoing conflict with the Roman (and later Byzantine) Empire. For over four centuries, these two superpowers engaged in nearly constant warfare, creating a military rivalry that shaped the geopolitical landscape of the ancient world:

Under Shapur I (240-272 CE), Sassanid forces captured the Roman Emperor Valerian—the only Roman emperor ever taken prisoner by an enemy power. Images of this triumph were carved into numerous rock reliefs and became a cornerstone of Sassanid imperial propaganda.

King Khosrow I Anushirvan (531-579 CE) developed sophisticated military tactics and siege warfare technologies that challenged Byzantine dominance. His reforms standardized military units and established a professional army.

The epic wars under Khosrow II Parviz (590-628 CE) nearly destroyed the Byzantine Empire before his eventual defeat. At its height, his forces captured Damascus, Jerusalem, and even Egypt, briefly restoring Persian control to territories not held since Achaemenid times.

The Battle of Nineveh (627 CE) against Byzantine Emperor Heraclius marked a turning point, beginning the empire's final decline.

The Sassanid military was anchored by the legendary ""Savaran"—heavily armored cavalrymen often depicted in rock reliefs. These elite horsemen, the original "knights in shining armor," wielded lances and compound bows with devastating effect on the battlefield. The Savaran were drawn from the noble houses of Persia, with each nobleman expected to maintain a specific number of mounted warriors.

Military innovations included:

The development of the heavy cataphract cavalry, with both rider and horse covered in chain mail or scale armor

The composite recurve bow, which could penetrate Roman armor at considerable distances

Naptha-based incendiary weapons, precursors to "Greek fire"

Sophisticated siege engines and techniques for undermining fortress walls

The use of war elephants, particularly in campaigns against Rome

The Sassanid army was organized decimally, with units of 10, 100, and 1,000 soldiers. Elite units included the Zhayedan (Immortals), a force of 10,000 hand-picked warriors who served as the imperial guard.

Religious Life and Cultural Identity

Zoroastrianism served as the state religion, providing spiritual and political legitimacy to the Sassanid dynasty. Under their rule, religious texts were systematically collected into what would become the Avesta, the sacred scripture of Zoroastrianism.

The Sassanid period represented a crucial time for Zoroastrian development:

The canon of sacred texts was established and standardized

High Priest Kartir institutionalized Zoroastrian orthodoxy

The sacred fire temples (atashkadeh) were built throughout the empire

The faith developed a clearer hierarchy and doctrinal framework

However, the empire also showed remarkable religious diversity:

Jewish communities thrived, establishing important centers of learning at places like Sura and Pumbedita. The Babylonian Talmud, one of Judaism's most foundational texts, was compiled under Sassanid rule.

Christian communities, though sometimes persecuted, maintained a strong presence, particularly in the western provinces. The Church of the East (Nestorian Christianity) gained formal recognition.

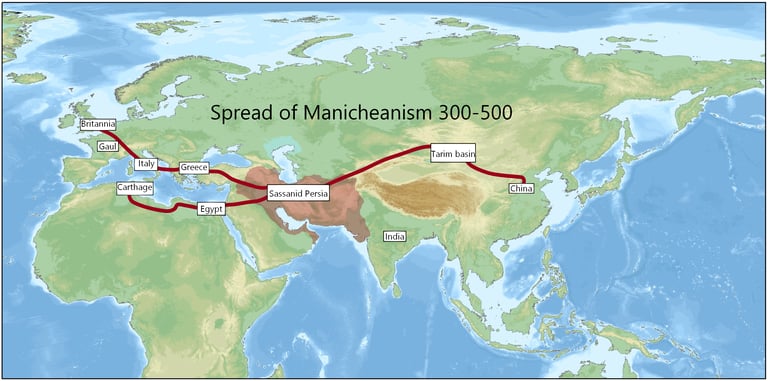

Manicheism emerged as a new faith during this period, founded by the prophet Mani during the reign of Shapur I. Though initially tolerated, Mani was eventually executed and his followers persecuted.

Buddhism spread through the eastern provinces, with monasteries established in Balkh and other eastern cities.

Hindu influences were present in the easternmost regions bordering India.

The religious policies of the Sassanids fluctuated between tolerance and persecution, often reflecting the political climate. During periods of conflict with Christian Rome, Christians within Sassanid territory sometimes faced suspicion and oppression.

Religious debates and theological discussions flourished, with the Sassanid court occasionally hosting interfaith dialogues between representatives of different religions—a remarkable practice for the ancient world.

Artistic and Cultural Achievements

Sassanid culture represents one of the high points of Persian artistic expression. Their distinctive aesthetic influenced regions from China to the Mediterranean:

Architecture: Massive barrel-vaulted halls, intricate stucco decorations, and geometric designs characterized Sassanid architecture, as seen in palaces like Ctesiphon with its famous arch (Taq-e Kisra), which stood as the world's largest unreinforced brick arch for over 1,300 years. Other significant structures included fire temples, palace complexes at Firuzabad and Bishapur, and the innovative round city of Gur (modern Firuzabad).

Metalwork: Elaborately decorated silver plates and vessels featuring royal hunting scenes became prestigious diplomatic gifts. Techniques included repoussé, gilding, and niello inlay. The iconic Sassanid silver plates often depicted the king hunting lions, boar, or other powerful animals—symbolizing royal power.

Textiles: Silk brocades with pearl-studded roundels and animal motifs were highly prized throughout the ancient world. Sassanid textiles were so valued that fragments have been found as far away as Viking burial sites in Scandinavia. The characteristic "Sassanid pearl roundel" with paired birds or beasts influenced textile design across Eurasia.

Rock Reliefs: Monumental carvings depicting royal investitures and military triumphs adorned cliff faces at sites like Naqsh-e Rustam and Taq-e Bostan. These served as imperial propaganda, showcasing the king's divine right to rule and military prowess.

Glassware: Sassanid craftsmen produced distinctive cut glass vessels that were exported widely. Their facet-cutting techniques and vessel forms influenced Roman and later Islamic glassmaking.

Music: Historical sources mention sophisticated musical traditions, with instruments including harps, lutes, drums, and flutes. Court musicians held high status, and musical theory was formally studied.

Garden Design: The concept of the Persian paradise garden (paridaeza) was refined during this period, featuring geometrical layouts, water channels, and formal plantings that would later influence garden design from Spain to India.

The Sassanid aesthetic—characterized by symmetry, intricate patterns, and stylized natural forms—would later influence Islamic art, Byzantine design, and even medieval European decorative traditions. Motifs like the winged crown, simurgh (mythical bird), and the tree of life became iconic elements in Persian art that endured long after the empire's fall.

Economic Power and Trade Networks

The Sassanids controlled crucial segments of the Silk Road, positioning their empire as a vital intermediary in East-West trade. Their strategic location allowed them to profit enormously from luxury goods passing between China, India, and the Mediterranean world.

Key economic achievements included:

A standardized currency system with remarkable stability. Sassanid silver drachms maintained consistent weight and purity for centuries, becoming a trusted international currency.

State-sponsored irrigation works that transformed agriculture. The innovative qanat underground aqueduct system allowed farming in arid regions, dramatically increasing agricultural output.

Royal workshops producing luxury goods for export, with state monopolies on certain goods ensuring quality control and substantial profits.

Control of key ports on the Persian Gulf, including Siraf and Rev-Ardashir, facilitating maritime trade with India, East Africa, and Southeast Asia.

Banking systems and commercial contracts that facilitated complex business transactions. Preserved documents show sophisticated financial arrangements, including loans, partnerships, and trading ventures.

Sassanid cities like Ctesiphon, Gundeshapur, and Bishapur became wealthy metropolitan centers where merchants from across Asia and Europe conducted business in massive bazaars under imperial protection. Ctesiphon, the capital, grew to become one of the world's largest cities, with a population estimated at 500,000 people.

The empire operated specialized industries, including

Silk production, after silkworm eggs were smuggled from China

Royal armories producing weapons and armor

Carpet weaving workshops creating the famous "Spring of Khosrow" carpet

Glass factories producing distinctive cut glass vessels

Paper-making facilities (in the later period)

Commercial activities were regulated through a system of standardized weights and measures, market inspectors, and customs officials who collected duties on goods entering the empire. Commercial law was well-developed, with specific regulations governing partnerships, contracts, and dispute resolution.

Intellectual and Scientific Contributions

The Sassanid period witnessed remarkable intellectual achievements that would later influence Islamic civilization:

The Academy of Gundeshapur became one of the ancient world's foremost centers of learning, particularly in medicine. Founded by Shapur I and expanded by Khosrow I, it brought together scholars from across the known world.

Scholars translated Greek, Indian, and Syriac texts, preserving knowledge that might otherwise have been lost. When Emperor Justinian closed the Platonic Academy in Athens in 529 CE, many Neo-Platonic philosophers found refuge in the Sassanid court.

Mathematical innovations, including early work on algebra, trigonometry, and the decimal system, flourished. The mathematician-astronomer Andarzaghar developed sophisticated methods for calculating planetary movements.

Medical knowledge advanced significantly, with sophisticated hospital systems and training methods. The physician Burzōē traveled to India to obtain medical texts, including works on toxicology and antidotes.

Astronomical observations were systematically conducted, resulting in accurate solar calendars and star catalogs. The zij (astronomical tables) compiled during this period would later influence Islamic astronomy.

Philosophy flourished, particularly after the arrival of Neo-Platonic philosophers from Athens. The schools of logical debate (munazara) developed formalized methods of argumentation.

Literary works proliferated, though many survive only in later translations. Court poets created elaborate epics celebrating royal deeds, while collections of wisdom literature like the "Counsel of Anushirvan" provided ethical and practical guidance.

The concept of a bimaristan (hospital) with specialized wards and training physicians originated during this period, later becoming a model for medieval Islamic medical institutions. The hospital at Gundeshapur included separate wards for different diseases, a pharmacy, and a medical library.

The Sassanids also developed an elaborate system of statecraft and political philosophy. Works like the "Letter of Tansar" and "Testament of Ardashir" outline sophisticated theories of governance, emphasizing the interdependence of religion and kingship, visualized as "twin pillars" supporting society.

Daily Life and Social Structure

Daily life in the Sassanid Empire was characterized by distinct social stratification yet also by remarkable urban development and cultural richness:

Urban Planning: Cities featured designated quarters for different professions and religions, with central markets (bazaars), fire temples, and administrative buildings. The innovative round city of Gur (Firuzabad) represented early urban planning with its precise geometric layout.

Housing: Elite residences featured central courtyards, reception halls, and private quarters, while commoners lived in simpler mud-brick structures. Archaeological excavations at sites like Bishapur reveal sophisticated domestic architecture with indoor plumbing and heating systems.

Diet and Cuisine: The typical diet included bread, rice, fruits, vegetables, dairy products, and meat for the wealthy. Wine consumption was common despite religious restrictions, with vineyards cultivated extensively. Specialized cookbooks from the period mention elaborate royal feasts with dozens of dishes.

Clothing: Dress indicated social status, with nobility wearing silk brocades, jewelry, and distinctive headgear. Men typically wore trousers, tunics, and cloaks, while women wore long dresses with head coverings. Royal figures were distinguished by their unique crowns and purple garments.

Family Structure: The family unit was patriarchal, with marriages often arranged for political or economic advantage among the elite. Polygamy was practiced primarily by the wealthy, while most common people lived in nuclear family units.

Legal System: Sassanid law was codified in the Madayan i Hazar Dadestan (Book of a Thousand Judgments), which addressed criminal punishment, property rights, inheritance, and commercial law. Courts operated at various levels, with judges appointed by royal authority.

Education: Formal education was primarily available to nobles, priests, and scribes, focusing on religious texts, literature, mathematics, and administrative skills. Training in specific crafts occurred through apprenticeship systems.

Entertainment: Public celebrations included Nowruz (Persian New Year), Mehregan (autumn festival), and various religious observances. Polo (chogan) was popular among the nobility, while hunting, board games like chess (chatrang), and musical performances provided recreation.

Archaeological evidence from sites throughout Iran, Iraq, and Central Asia reveals a material culture of considerable sophistication, with urban households using glazed ceramics, glass vessels, metal implements, and textiles that indicate widespread prosperity in the empire's heartlands.

Decline and Legacy

The Sassanid Empire's decline began after the costly wars with Byzantium under Khosrow II. Weakened by internal strife and exhausted by centuries of warfare, the empire faced a new threat from the Arab Muslim armies emerging from the Arabian Peninsula. A succession crisis following Khosrow II's murder in 628 CE led to political instability, with over ten rulers claiming the throne in just four years. This chaotic situation, combined with a devastating plague and economic recession, left the empire vulnerable.

The decisive Battle of Qadisiyyah in 636 CE saw Arab forces defeat the Sassanid army, followed by the fall of Ctesiphon. Despite continued resistance, particularly under General Rustam Farrokhzad, the empire gradually lost territory. In 651 CE, after a series of decisive defeats, the last Sassanid king, Yazdegerd III, was killed near Merv, marking the end of the empire.

Yet the Sassanid legacy endured:

Administrative Continuity: The early Islamic caliphates largely maintained Sassanid administrative structures, tax systems, and even employed former Sassanid officials.

Cultural Persistence: The cultural concept of "Iranshahr" (the domain of Iran) survived the political collapse, maintaining Persian identity through centuries of foreign rule.

Artistic Influence: Sassanid decorative motifs, architectural elements, and aesthetic principles profoundly shaped Islamic art, appearing in Umayyad and Abbasid palaces, textiles, and metalwork.

Religious Developments: While Zoroastrianism declined as the state religion, many of its concepts influenced aspects of Islamic thought. Some Zoroastrian communities continued to exist in Iran, while others migrated to India, becoming the modern Parsi community.

Political Theory: The Sassanid model of divine kingship influenced concepts of rulership throughout the medieval Middle East and Central Asia.

Scientific and Philosophical Transmission: Translations of Pahlavi scientific and philosophical works into Arabic during the early Islamic period preserved crucial knowledge and contributed to the Islamic Golden Age.

Literary Heritage: The epic traditions and historical chronicles of the Sassanids informed later Persian literature, most notably Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, which preserved many pre-Islamic Iranian myths and historical accounts.

Military Techniques: Sassanid heavy cavalry tactics and armor designs influenced Byzantine, Arab, and Turkic military developments.

The Arab conquerors themselves, though bringing a new religion and political order, adopted many aspects of Sassanid culture and governance. As the Persian poet Ferdowsi would later write in his epic Shahnameh, "The Sassanids departed, but their customs remained."

The Persian cultural revival under the Sassanids created a distinctive Iranian identity that would survive centuries of foreign rule, emerging again under dynasties like the Samanids, Buyids, and eventually the Safavids. This resilience demonstrates the profound impact of Sassanid civilization—an empire that not only rivaled Rome in its day but whose legacy continues to shape the cultural landscape of the Middle East and Central Asia.

Archaeological Discoveries and Modern Research

Modern archaeological discoveries continue to enhance our understanding of the Sassanid Empire:

Palace Excavations: Work at sites like Bishapur, Firuzabad, and Ctesiphon has revealed sophisticated architectural techniques and urban planning.

The Sasanian Royal Road: Satellite imagery and ground surveys have mapped segments of the empire's extensive road network, which connected major cities and facilitated trade and military movements.

Underwater Archaeology: Excavations in the Persian Gulf have discovered Sassanid port facilities and shipwrecks, providing insights into maritime trade networks.

Border Fortifications: The Sassanid-built Great Wall of Gorgan (the "Red Snake") in northeastern Iran—the second-longest defensive wall in antiquity after the Great Wall of China—has been extensively studied, revealing sophisticated military engineering.

Digital Reconstruction: Advanced imaging techniques have allowed researchers to create digital reconstructions of major sites like the Taq-e Kisra arch and the palace complex at Ctesiphon.

Coin Analysis: Numismatic studies have provided crucial chronological information and insights into economic conditions throughout the empire.

Contemporary scholars have revised earlier Western-centric interpretations that viewed the Sassanids merely as Rome's eastern antagonists, now recognizing them as a sophisticated civilization with wide-ranging influence across Asia. Recent research emphasizes the empire's role in facilitating cultural exchange between East and West, its religious complexity, and its administrative innovations.

The Sassanid Empire represents a crucial bridge between the ancient and medieval worlds. For over four centuries, it stood as Rome's equal, creating a sophisticated civilization with far-reaching influence. Its cultural, political, and artistic achievements left an indelible mark on countless societies across Europe and Asia.

This "Persian Renaissance" preserved and developed ancient Iranian traditions while absorbing influences from Greece, India, and China—creating a cosmopolitan culture that would later contribute significantly to Islamic civilization. From its carefully structured society to its magnificent architectural monuments, from its philosophical depth to its military might, the Sassanid Empire exemplifies the heights of pre-modern state formation and cultural achievement.

Despite its eventual fall, the Sassanid legacy continues to resonate in everything from architectural styles to administrative concepts, from religious thought to military traditions. In understanding this remarkable empire, we gain invaluable insights into the formation of the medieval world and the rich tapestry of Middle Eastern history.

Further Reading

For those interested in exploring the fascinating world of Sassanid Persia more deeply, the following resources offer excellent starting points:

"The Sasanian Empire: The Rise and Fall of an Empire" by Touraj Daryaee

"Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire" by Josef Wiesehöfer

"The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods"

"Art of the Sasanian Period" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

"Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire" by Parvaneh Pourshariati

"Sasanian Iran, 224-651 CE: Portrait of a Late Antique Empire" by Matthew P. Canepa

"The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period" by Amélie Kuhrt

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚