The Maurya Empire: Ancient India's First Pan-Continental Dynasty (322-185 BCE)

Discover the Maurya Empire (322-185 BCE): India's first pan-continental dynasty. Explore Chandragupta, Ashoka's transformation, governance systems, and lasting legacy.

EMPIRES/HISTORYHISTORYINDIAN HISTORY

Sachin K Chaurasiya

1/31/202611 min read

The Maurya Empire stands as one of history's most remarkable political achievements—a vast Iron Age civilization that unified the Indian subcontinent for the first time, established sophisticated governance systems, and left an indelible mark on South Asian culture that resonates nearly 2,400 years later.

Origins and Foundation of the Mauryan Dynasty

The Maurya Empire emerged from the political chaos following Alexander the Great's invasion of the Indian subcontinent in 326 BCE. Chandragupta Maurya, a young warrior of uncertain origins, capitalized on the power vacuum left by Alexander's withdrawal and the weakening Nanda dynasty that ruled Magadha (present-day Bihar).

With guidance from his mentor Chanakya (also known as Kautilya), a brilliant strategist and author of the Arthashastra—an ancient treatise on statecraft, economics, and military strategy—Chandragupta overthrew the Nanda ruler Dhana Nanda around 322 BCE. This marked the beginning of what would become the largest empire in Indian history until the Mughal period.

Chandragupta Maurya: Empire Builder and Strategic Visionary

Chandragupta's rise from relative obscurity to emperor demonstrates exceptional military and political acumen. Ancient sources suggest he may have met Alexander during the Macedonian conquest, though this remains debated among historians. What's undisputed is his methodical conquest strategy that combined military force with diplomatic alliances.

By 305 BCE, Chandragupta had expanded his territory to include most of the Indian subcontinent, engaging in conflict with Seleucus I Nicator, Alexander's successor who controlled the eastern Hellenistic territories. The Seleucid-Mauryan war concluded with a peace treaty where Seleucus ceded territories in present-day Afghanistan, Balochistan, and parts of Persia in exchange for 500 war elephants—a strategic trade that reflected the Mauryan military's elephant warfare superiority.

Greek ambassador Megasthenes visited Chandragupta's court in Pataliputra (modern Patna) and documented his observations in "Indica," providing invaluable insights into Mauryan society, governance, and military organization. His accounts describe Pataliputra as a magnificent city with 64 gates and a wooden palisade, surrounded by a deep moat.

Territorial Expansion and Geographic Extent

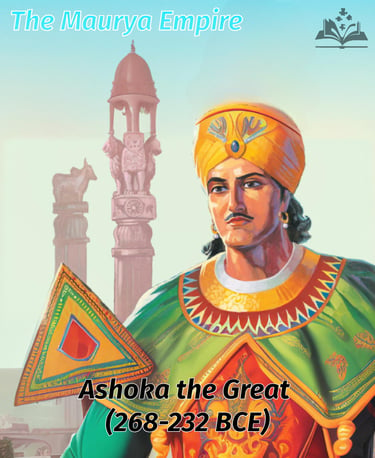

At its zenith under Emperor Ashoka (268-232 BCE), the Maurya Empire controlled approximately 5 million square kilometers, stretching from present-day Afghanistan and Balochistan in the northwest to Bengal and Assam in the east, and extending southward to Karnataka. Only the southern tip of the Indian peninsula and parts of present-day Odisha (before the Kalinga conquest) remained outside Mauryan control.

The empire's vast territory encompassed diverse ecological zones, climates, languages, and cultures—a diversity that presented both opportunities and challenges for centralized governance. The Mauryas developed innovative administrative systems to manage this complexity effectively.

Administrative Genius: The Mauryan Governance System

The Mauryan administrative framework, largely documented in Chanakya's Arthashastra and corroborated by Megasthenes' accounts, represents one of the ancient world's most sophisticated bureaucratic systems.

Central Administration and Imperial Structure

The emperor held absolute authority but governed through an extensive bureaucracy organized into departments (adhyakshas). These departments managed everything from tax collection and agriculture to weights and measures, mining, forestry, and commerce. The council of ministers (mantriparishad) advised the emperor on policy matters, while a network of spies and informants (reported to number in the thousands) ensured information flow and monitored potential threats.

Provincial and Local Governance

The empire was divided into provinces (likely four or five major divisions), each governed by a royal prince or trusted administrator. These provinces were further subdivided into districts and villages, creating a hierarchical administrative structure with clear chains of command.

The Arthashastra details a remarkably modern-sounding civil service, with officials appointed based on competence rather than solely on birth or lineage. Official salaries were standardized, and mechanisms existed to prevent corruption, though enforcement varied.

Economic Management and Revenue Systems

The Mauryan state maintained a detailed revenue system based primarily on agricultural taxation (typically one-sixth of produce, though rates varied). The empire standardized weights and measures, facilitating trade across vast distances. State monopolies existed for critical industries, including mining, salt production, and weapons manufacturing.

Archaeological evidence suggests sophisticated irrigation systems, including reservoirs and canals, that enhanced agricultural productivity. The state invested in infrastructure—roads, rest houses (dharmashalas), and wells—that facilitated both commerce and administrative control.

The Kalinga War and Ashoka's Transformation

The most pivotal event in Mauryan history occurred around 261 BCE when Emperor Ashoka invaded Kalinga (present-day Odisha), one of the few independent regions remaining outside Mauryan control. Ancient sources, including Ashoka's own rock edicts, describe a catastrophic conflict with approximately 100,000 deaths and 150,000 deportations.

The Kalinga War's unprecedented violence profoundly affected Ashoka. His 13th Rock Edict expresses deep remorse for the suffering caused, marking a dramatic shift in imperial philosophy from conquest through force (digvijaya) to conquest through righteousness (dharmavijaya).

Ashoka's Dhamma and Ethical Governance

Following his conversion to Buddhism and spiritual transformation, Ashoka promoted dhamma—a moral code emphasizing non-violence (ahimsa), religious tolerance, respect for elders and teachers, truthfulness, and compassion toward all living beings. This wasn't strictly Buddhist doctrine but rather a syncretic ethical framework drawing from Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu philosophies.

Ashoka appointed special officers called dhamma-mahamattas to propagate these principles and ensure their implementation. He famously renounced aggressive military expansion, instead focusing on moral leadership and welfare governance.

The Ashokan Edicts: Ancient India's Written Legacy

Ashoka's most enduring contribution is his system of inscriptions carved on pillars and rocks throughout his empire, written in Prakrit using the Brahmi script (with some in Greek and Aramaic in the northwest). These edicts, numbering over 30 major inscriptions, represent the earliest deciphered written records in Indian history.

The edicts cover diverse topics: moral guidance, administrative policies, religious tolerance, animal welfare, medicinal herb cultivation, and construction of public utilities. They provide unprecedented historical evidence about Mauryan governance, ideology, and geographic extent.

The Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath, featuring four Asiatic lions standing back-to-back, was adopted as India's national emblem in 1950. The Ashoka Chakra (wheel) from the same pillar appears on India's national flag, demonstrating the emperor's lasting symbolic importance.

Art, Architecture, and Cultural Achievements

Monumental Architecture and Sculptural Excellence

Mauryan architecture represents a significant advancement in Indian building traditions, marked by the introduction of stone construction on a monumental scale. The polished sandstone pillars, often reaching 15 meters in height and weighing up to 50 tons, demonstrate remarkable quarrying, transportation, and sculpting capabilities.

The famous Mauryan polish—a lustrous, mirror-like finish on stone surfaces—remains technically impressive. Modern researchers have attempted to replicate this finish without complete success, suggesting sophisticated knowledge of stone treatment and polishing techniques.

Cave architecture flourished during this period, with the Barabar Caves in Bihar representing the earliest surviving rock-cut caves in India. These caves, donated by Ashoka to the ascetic Ajivika sect, feature highly polished interiors and demonstrate advanced stone-cutting technology.

Urban Planning and Infrastructure

Pataliputra, the Mauryan capital, exemplified advanced urban planning. Archaeological excavations reveal a planned city with wide streets laid out in a grid pattern, sophisticated drainage systems, and monumental wooden structures. The royal palace, described by Megasthenes as surpassing the splendor of Persian palaces, covered approximately 10 square kilometers.

The Mauryas constructed an extensive road network, with the Royal Highway (Uttarapatha) connecting Pataliputra to Taxila in the northwest, spanning over 2,500 kilometers. Rest houses positioned at regular intervals provided travelers with accommodation and amenities.

Scientific and Intellectual Progress

The Arthashastra reveals a sophisticated understanding of economics, political science, military strategy, and social organization. The text discusses everything from espionage techniques and cryptography to agricultural practices and mining operations.

Mauryan astronomers maintained observational records, and medical practitioners drew from Ayurvedic traditions. The period saw significant literary activity, including early Buddhist texts and grammatical works building on Panini's earlier Sanskrit grammar.

Military Organization and Warfare

The Mauryan military was among the ancient world's largest and most organized fighting forces. Megasthenes estimated the standing army at 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 war elephants, though modern historians consider these figures potentially inflated.

Military Structure and Strategy

The army was organized into specialized divisions managed by separate departments overseeing infantry, cavalry, chariots, elephants, navy, and logistics. A war council coordinated military operations and strategic planning.

War elephants formed a distinctive element of Mauryan military power. These massive animals, equipped with protective armor and mounted with archers or spearmen, provided psychological impact and tactical advantage in battles. The Mauryan elephant corps was legendary throughout the ancient world.

Weapons and Military Technology

Archaeological evidence reveals sophisticated metallurgy with iron weapons, including swords, spears, arrows, and protective armor. The Mauryans employed various siege weapons, though specific details remain limited.

Naval forces patrolled rivers and coastal waters, protecting trade routes and enforcing imperial authority. The Arthashastra discusses naval warfare, ship construction, and maritime trade regulation, indicating significant naval capabilities.

Economic System and Trade Networks

Agricultural Foundation and Rural Economy

Agriculture formed the economic bedrock of the Mauryan Empire. The state actively promoted agricultural expansion through irrigation projects, land grants, and resettlement programs. Surplus production supported urban populations, the military, and the administrative apparatus.

The Arthashastra details crop rotation practices, seasonal planting schedules, and agricultural techniques designed to maximize yields. State officials monitored agricultural production, assessed land quality for taxation purposes, and maintained grain reserves for famine relief.

Commerce, Trade, and Urban Economy

Extensive trade networks connected the Mauryan Empire to the Hellenistic world, Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and beyond. Merchants traded textiles, spices, precious stones, metals, and manufactured goods. The discovery of Mauryan coins and artifacts in distant locations confirms far-reaching commercial connections.

Urban centers hosted vibrant marketplaces regulated by officials who standardized weights and measures, collected taxes, and adjudicated commercial disputes. Guilds (shrenis) organized craftsmen and merchants, setting quality standards and protecting trade interests.

Currency and Monetary System

The Mauryas issued standardized coins, primarily silver and copper punch-marked coins bearing various symbols. This facilitated commerce, enabled consistent taxation, and demonstrated state authority. Regional variations existed, but increasing standardization occurred under central authority.

Social Structure and Daily Life

Caste System and Social Organization

Mauryan society operated within the varna system (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras), though the Arthashastra and Buddhist texts suggest greater social mobility than later periods. Urban centers particularly offered opportunities for skilled individuals regardless of birth status.

Greek accounts describe seven social classes, differing from the traditional four-varna structure, suggesting either misunderstanding of Indian social categories or actual complexity in Mauryan social organization.

Religious Landscape and Tolerance

The Mauryan period witnessed significant religious diversity and, particularly under Ashoka, remarkable tolerance. Buddhism gained royal patronage but coexisted with Hinduism, Jainism, Ajivikism, and various local cults. Ashoka's edicts explicitly promote respect for all religious sects and discourage sectarian conflict.

The Third Buddhist Council, convened under Ashoka's patronage around 250 BCE in Pataliputra, standardized Buddhist doctrine and dispatched missionaries across Asia, initiating Buddhism's transformation into a pan-Asian religion.

Education and Knowledge Transmission

Education occurred in various settings: royal courts, monastic institutions, forest academies (gurukulas), and urban centers. Brahmins traditionally served as teachers, though Buddhist and Jain institutions increasingly provided alternative educational pathways.

Taxila emerged as a renowned center of learning, attracting students from across the subcontinent and beyond. Curricula included religious texts, philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and statecraft.

Decline and Fragmentation

The Mauryan Empire began fragmenting after Ashoka's death around 232 BCE. Multiple factors contributed to this decline:

Weak Successors and Succession Struggles

Ashoka's successors lacked his administrative capabilities and political vision. The empire split into western and eastern portions, with different branches of the Mauryan family ruling each division. Internecine conflicts weakened central authority.

Economic and Administrative Strain

Maintaining the vast bureaucracy, military, and public works required enormous resources. Some historians argue Ashoka's emphasis on moral governance and reduced military activity weakened imperial defenses and revenue generation.

Regional Aspirations and External Pressures

Provincial governors and regional rulers increasingly asserted independence as central authority weakened. The northwest faced invasions from Greco-Bactrian kingdoms, while indigenous rulers in the south consolidated power.

The Final Collapse

The last Mauryan emperor, Brihadratha, was assassinated around 185 BCE by his commander-in-chief, Pushyamitra Shunga, who established the Shunga dynasty. This marked the definitive end of the Mauryan Empire, though its influence persisted through successor states.

Enduring Legacy and Historical Significance

Political and Administrative Impact

The Mauryan model of centralized administration, bureaucratic organization, and systematic governance influenced subsequent Indian empires, including the Guptas and Mughals. The concept of chakravartin (universal monarch) governing through dhamma rather than mere force became an ideal in Indian political thought.

Cultural and Religious Influence

Ashoka's promotion of Buddhism initiated its spread across Asia, transforming a regional Indian religion into a world religion. Mauryan artistic styles influenced subsequent Indian art and architecture. The Brahmi script, used in Ashokan edicts, became the ancestor of most modern Indian scripts.

Modern Relevance and Symbols

Independent India consciously drew on Mauryan symbolism for nation-building. The Ashoka Chakra on the national flag, the Lion Capital as the national emblem, and the motto "Satyameva Jayate" (Truth Alone Triumphs, from the Mundaka Upanishad, popularized during the Mauryan period) connect modern India to this ancient empire.

Archaeological and Historical Research

Ongoing archaeological excavations continue revealing Mauryan sites, artifacts, and inscriptions. Advanced techniques, including radiocarbon dating, satellite imagery, and geophysical surveys, are refining understanding of Mauryan chronology, urban planning, and trade networks.

Recent discoveries include previously unknown Ashokan edicts, Mauryan-era urban sites in peninsular India, and evidence of Mauryan maritime trade with Southeast Asia and the Mediterranean world.

Mauryan Resonance Through Millennia

The Maurya Empire's significance extends far beyond its geographic expanse or temporal duration. It demonstrated that diverse populations across vast territories could be governed through systematic administration, economic integration, and shared ethical frameworks rather than merely through military force.

Ashoka's transformation from conqueror to compassionate ruler who renounced aggressive warfare presents an enduring model of leadership evolution. His edicts, carved in stone across his empire, speak across centuries with messages of tolerance, compassion, and ethical governance that remain relevant in our contemporary world.

For modern India and the broader South Asian region, the Mauryan period represents a foundational era when political unity, administrative sophistication, and cultural synthesis created frameworks that influenced subsequent civilizations. The empire's legacy lives on in governmental structures, artistic traditions, religious practices, and philosophical concepts that continue shaping the subcontinent.

The Maurya Empire reminds us that great civilizations are built not just through conquest and control, but through vision, organization, cultural synthesis, and ethical foundations that transcend their immediate historical moment to influence future generations across millennia.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Who founded the Maurya Empire, and when?

Chandragupta Maurya founded the Maurya Empire around 322 BCE after overthrowing the Nanda dynasty with assistance from his mentor Chanakya. The empire lasted until approximately 185 BCE.

Q: What was the capital of the Mauryan Empire?

Pataliputra, located near modern-day Patna in Bihar, served as the Mauryan capital. It was described by Greek ambassador Megasthenes as one of the ancient world's most magnificent cities.

Q: Why is Ashoka considered the greatest Mauryan emperor?

Emperor Ashoka is renowned for his transformation after the brutal Kalinga War, his promotion of Buddhist principles and ethical governance (dhamma), and his system of rock and pillar edicts that provide invaluable historical documentation. His influence on spreading Buddhism across Asia and his model of compassionate governance make him one of history's most significant rulers.

Q: How large was the Maurya Empire at its peak?

At its zenith under Ashoka, the Maurya Empire controlled approximately 5 million square kilometers, encompassing most of the Indian subcontinent from Afghanistan to Bengal and extending south to Karnataka—the largest Indian empire before the Mughal period.

Q: What language and script did the Mauryans use?

The Mauryan administration used Prakrit languages written in Brahmi script for most of Ashoka's edicts within India. In the northwest, some inscriptions appeared in Greek and Aramaic to accommodate local populations. Sanskrit remained the language of religious and scholarly texts.

Q: What caused the decline of the Maurya Empire?

The Mauryan decline resulted from multiple factors, including weak successors after Ashoka, economic strain from maintaining a vast bureaucracy and military, increasing independence of provincial governors, external invasions particularly in the northwest, and internal political instability culminating in the assassination of the last emperor, Brihadratha, around 185 BCE.

Q: What is the Arthashastra, and why is it important?

The Arthashastra is an ancient treatise on statecraft, economics, and military strategy attributed to Chanakya (Kautilya), Chandragupta's mentor. It provides detailed insights into Mauryan governance, administration, economic policy, and military organization, serving as both a practical manual for rulers and an invaluable historical source.

Q: Did the Mauryan Empire have contact with ancient Greece and Rome?

Yes, the Mauryan Empire maintained diplomatic and commercial relations with Hellenistic kingdoms. Seleucus I Nicator sent ambassador Megasthenes to Chandragupta's court. Trade networks connected the Mauryan Empire to the Mediterranean world, with goods and ideas flowing between these civilizations.

Q: What happened to Buddhism after the Maurya Empire?

Buddhism continued flourishing in India for centuries after the Mauryan collapse, reaching its zenith during the Gupta period. However, it eventually declined in the Indian subcontinent while spreading extensively across Asia—to Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, China, Korea, and Japan—partly due to missionary efforts initiated during Ashoka's reign.

Q: What archaeological evidence exists for the Maurya Empire?

Archaeological evidence includes Ashokan pillars and rock edicts, remains of Pataliputra including portions of the wooden palisade, Mauryan coins, pottery, seals, the Barabar Caves, fortification remains at various sites, and artifacts recovered from excavations across the former empire's territory. These findings corroborate and supplement literary sources.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚