The Khwarazmian Empire: Central Asia's Forgotten Superpower

Discover the forgotten medieval powerhouse that once dominated Central Asia and challenged both East and West. The Khwarazmian Empire (1097–1231) controlled vast territories along the Silk Road before meeting a catastrophic end at the hands of Genghis Khan. This comprehensive analysis explores the empire's meteoric rise, golden age of cultural achievement, dramatic collapse, and enduring legacy in modern Central Asian identity.

HISTORYEDUCATION/KNOWLEDGEEMPIRES/HISTORY

Keshav Jha

3/25/202513 min read

The Khwarazmian Empire stands as one of history's most fascinating yet often overlooked medieval powers. At its peak in the early 13th century, this formidable Central Asian empire stretched from the shores of the Caspian Sea to the borders of India, encompassing modern-day Iran, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and parts of Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Despite its impressive territorial extent and cultural significance, the empire's meteoric rise and catastrophic collapse have received less attention than other medieval empires. This article explores the empire's origins, golden age, dramatic downfall, and lasting legacy in Central Asian history.

Origins and Early Development

The Khwarazmian Empire emerged from the region of Khwarazm, situated in the fertile delta where the Amu Darya (historically known as the Oxus) river flows into the Aral Sea. This strategic location made it a natural crossroads for trade and cultural exchange between East and West.

Originally a province of the Seljuk Empire, Khwarazm was governed by appointed officials bearing the title "Khwarazm-Shah." In the late 11th century, Anushtegin Gharchai, a former Turkish slave who rose to prominence in the Seljuk administration, was appointed as governor of the region. His descendants would transform this governorship into an independent dynasty.

The foundation for true independence was laid by Qutb ad-Din Muhammad I (ruled 1097–1127), who began the process of breaking away from Seljuk control. However, it was his son, Ala ad-Din Atsiz (ruled 1127–1156), who truly established Khwarazmian autonomy through military campaigns and strategic alliances, deftly playing competing powers against each other.

Challenging the Seljuks and Qarakhanids

Atsiz's rule was marked by a complex dance of rebellion and submission. He repeatedly revolted against his Seljuk overlords, only to be defeated and forced to reaffirm his loyalty. The most notable of these conflicts occurred with Sultan Sanjar, the last great Seljuk ruler. Despite military setbacks, Atsiz gradually consolidated his power through administrative reforms and by strengthening control over trade routes.

His successor, Il-Arslan (ruled 1156–1172), continued the expansion policy while maintaining nominal allegiance to the Seljuks. He extended Khwarazmian influence into Transoxiana, coming into conflict with the Qarakhanids and the rising power of the Kara-Khitai. It was during this period that the Khwarazmians began to develop their distinctive military system, combining Turkic horse archers with more conventional infantry forces.

Tekesh and the Path to Empire

Under Sultan Tekesh (ruled 1172-1200), the Khwarazmian state truly began its transformation into an empire. Tekesh's reign saw significant territorial expansion and the final break from Seljuk suzerainty. His most decisive victory came in 1194 when he defeated the last Seljuk Sultan of Iraq, Toghrul III, effectively ending Seljuk power in Persia.

Tekesh employed both military might and marriage alliances to advance Khwarazmian interests. He secured control over Khorasan and extended his influence into northern Persia. By the time of his death, the groundwork had been laid for his son Muhammad II to elevate the Khwarazmian state to imperial status.

The Golden Age

The empire reached its zenith under Ala ad-Din Muhammad II (ruled 1200–1220), who expanded Khwarazmian territory dramatically through conquest and diplomatic maneuvering. By 1212, he had conquered most of Persia and Central Asia, including the wealthy cities of Samarkand and Bukhara. The Khwarazmian Empire became a formidable power with a strong military, thriving economy, and rich cultural life.

Military Campaigns and Territorial Expansion

Muhammad II's military accomplishments were impressive by any standard. Early in his reign, he defeated the Ghurids, acquiring parts of Afghanistan and extending influence toward the Indian subcontinent. In 1210, he conquered the Kara-Khitai Empire after backing a rebellion within their territory, effectively doubling the size of his realm.

His most ambitious campaign came in 1217, when he launched an attack on the Abbasid Caliphate, seeking to replace the Caliph in Baghdad with a puppet ruler. Though this campaign ultimately failed due to unexpected weather conditions—his army was caught in an unusually severe winter in the Zagros Mountains—it demonstrated the empire's military capabilities and imperial ambitions.

Administrative Structure

The Khwarazmian Empire developed a sophisticated administrative system that adapted elements from Persian, Turkish, and Islamic governance traditions. The empire was divided into provinces, each governed by an appointed official who answered directly to the Shah. In many cases, these governors were members of the royal family or trusted military commanders.

At the center of the empire stood the Shah himself, who maintained absolute authority in theory, though practical limitations often required cooperation with local elites and religious authorities. The administration made extensive use of Persian bureaucratic traditions, with a complex system of record-keeping and taxation.

The empire's prosperity was built on several pillars:

Trade: Controlling key sections of the Silk Road, the Khwarazmians facilitated and taxed trade between China, India, the Middle East, and Europe. Their cities became important commercial hubs where merchants from diverse backgrounds exchanged goods and ideas. The empire minted its own distinctive coins, which have been found as far away as Scandinavia, testifying to the extent of their trade networks.

Agriculture: The fertile river valleys supported extensive irrigation systems, enabling agricultural prosperity even in this arid region. Cotton, fruits, and grains were cultivated in abundance. The Khwarazmians maintained and expanded the ancient irrigation networks of the region, some dating back to Achaemenid times, constructing elaborate canal systems that transformed desert areas into productive farmland.

Craftsmanship: Khwarazmian artisans were renowned for their metalwork, textiles, ceramics, and architectural achievements. The empire's cities boasted impressive mosques, madrasas, and palaces. Khwarazmian textiles, particularly their silk and cotton fabrics, were highly prized in international markets. Their distinctive blue-glazed ceramics showed influence from both Chinese porcelain and Persian artistic traditions.

Intellectual Life: The court attracted scholars, poets, and scientists from across the Islamic world. The Khwarazmian elite patronized the arts and sciences, contributing to the Islamic Golden Age. Among the notable scholars associated with the Khwarazmian court was al-Zamakhshari, a renowned linguist and Quranic commentator whose works remain influential in Islamic scholarship to this day.

Cultural and Religious Dynamics

Under Muhammad II's rule, the empire became a true multiethnic state, incorporating Turkic, Persian, and Arab populations. Persian served as the administrative language, while Turkic remained important in military contexts. Islam was the dominant religion, but the empire maintained a degree of religious tolerance typical of many medieval Islamic states.

The religious landscape of the empire was complex. The ruling elite generally followed Sunni Islam, though there were significant Shia minorities in various regions. Sufism gained increasing importance during this period, with several important Sufi orders establishing themselves in Khwarazmian cities. Christian and Buddhist communities also existed, particularly in the eastern territories formerly under Kara-Khitai rule.

The architectural legacy of the Khwarazmians blended Turkish, Persian, and local Central Asian elements. Their buildings were characterized by elaborate brickwork, geometric patterns, and increasingly large central domes. The Great Mosque of Urgench and the mausoleum of Sultan Tekesh exemplify this distinctive architectural style.

Court Life and Social Structure

Court life in the Khwarazmian Empire combined Turkish military traditions with Persian cultural refinements. The Shah maintained a large personal guard of elite warriors, many of whom were mamluks (slave soldiers) of Turkish origin. Royal processions, hunts, and feasts were important displays of imperial power and wealth.

Beneath the ruling elite, society was stratified into various classes, including merchants, artisans, religious scholars, peasants, and slaves. Urban centers were particularly diverse, with quarters often organized along ethnic or professional lines. Market inspectors (muhtasibs) enforced commercial regulations and Islamic moral codes in the bustling bazaars.

Women in the Khwarazmian Empire, particularly those of the elite classes, could wield significant influence. The mother of Muhammad II, Terken Khatun, was especially powerful, maintaining her own court and even issuing orders that sometimes contradicted those of her son—a factor that would contribute to the empire's disunity in its final crisis.

The Mongol Invasion and Collapse

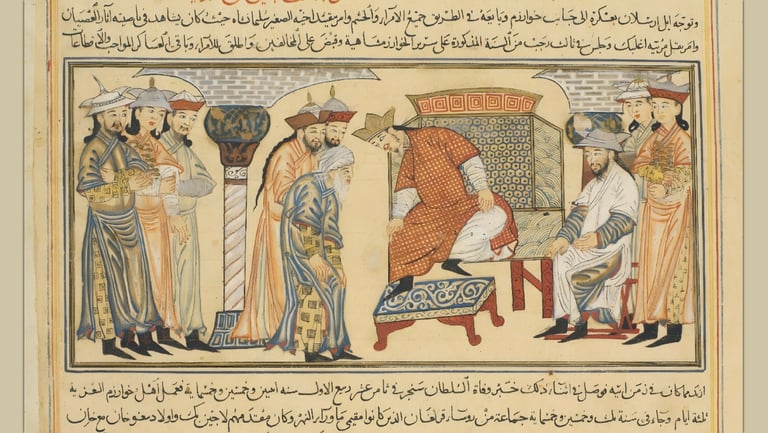

The Khwarazmian Empire's downfall came swiftly and catastrophically. In 1218, a diplomatic incident triggered one of history's most devastating military campaigns. When Mongol trade caravans sent by Genghis Khan arrived in Khwarazm, the local governor of Otrar suspected them of espionage and ordered their execution. This grave misjudgment, compounded by Shah Muhammad II's subsequent beheading of Mongol ambassadors sent to resolve the situation, provoked Genghis Khan's wrath.

Strategic Miscalculations

Before the crisis, Muhammad II had actually received correspondence from Genghis Khan proposing peaceful relations. The Mongol ruler addressed him as "my son," suggesting a partnership between equals that nevertheless implied Mongol superiority—an implication that may have offended the proud Khwarazmian ruler.

When the crisis erupted, Muhammad II's response revealed critical strategic errors. Rather than concentrating his forces for decisive battles, he dispersed his army of approximately 400,000 soldiers across various cities. This decision stemmed partly from his mother Terken Khatun's influence and partly from an overestimation of the defensive capabilities of his urban centers.

The Mongol War Machine

The ensuing Mongol invasion of 1219–1221 was carried out with remarkable speed and brutality. The Mongol forces, though numerically inferior to the Khwarazmian army, employed superior tactics, mobility, and psychological warfare. Cities that resisted were subjected to complete destruction, with entire populations massacred. Bukhara, Samarkand, and other major Khwarazmian cities fell one by one.

Genghis Khan divided his forces into multiple columns to attack the empire from different directions simultaneously. His generals, including the brilliant Subedei and Jebe, executed complex maneuvers across difficult terrain with remarkable precision. The Mongols also demonstrated advanced siege warfare capabilities, quickly adapting to the challenge of taking fortified cities despite their nomadic origins.

Their psychological warfare was equally sophisticated. They deliberately spread rumors of their brutality, offering generous terms to cities that surrendered immediately while utterly destroying those that resisted. This strategy created a powerful incentive for submission and sowed discord among defending populations.

The Fall of Great Cities

The fall of Bukhara in February 1220 marked the beginning of the end. Upon entering the conquered city, Genghis Khan reportedly went to the main mosque and declared himself the "Flail of God." The city's artisans and skilled workers were deported to Mongolia, while many others were massacred or pressed into service as human shields for future assaults.

Samarkand, despite its strong fortifications and garrison of 110,000 soldiers, fell after just five days. Urgench, the capital, resisted more stubbornly, holding out for several months before falling in April 1221. The Mongols rerouted the Amu Darya river to flood the city after its capture—a devastating final blow to what had been one of Central Asia's greatest urban centers.

The Last Shah and the Fugitive Court

Shah Muhammad II, rather than confronting the invaders directly, fled westward and eventually died on a small island in the Caspian Sea in 1220, a broken ruler watching his empire crumble. His son, Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, mounted a valiant but ultimately futile resistance, winning some battles but eventually being forced to flee to India in 1221.

Jalal ad-Din's last stand at the Battle of the Indus in 1221 impressed even Genghis Khan. After defeating his forces, the Mongol conqueror reportedly pointed to the fleeing Shah as he swam across the Indus River and remarked to his sons, "Now that is a man worthy to have sons."

The devastation wrought by the Mongol invasion was profound. Contemporary accounts describe cities reduced to rubble, irrigation systems destroyed, and entire regions depopulated. The political entity known as the Khwarazmian Empire ceased to exist, its territories incorporated into the rapidly expanding Mongol Empire.

Jalal ad-Din's Later Campaigns

Though the Khwarazmian Empire had collapsed, Jalal ad-Din continued to fight. After gathering a new army in India, he returned to Persia around 1224 and briefly established a domain in western Iran and Iraq. For almost a decade, he waged war against the Mongols, Seljuk Turks of Rum, and the Ayyubids of Syria before being killed by Kurdish bandits in 1231.

His tenacious resistance became legendary, though ultimately it could not reverse the catastrophic losses the Khwarazmians had suffered. Some Khwarazmian military units survived as the so-called "Khwarezmian mercenaries," who would later play a significant role in Middle Eastern politics, particularly in the Ayyubid territories, where they captured Jerusalem in 1244.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Though the Khwarazmian Empire's existence was relatively brief, its legacy lives on in several ways:

Cultural Synthesis: The empire represented an important chapter in Central Asia's history of cultural exchange and synthesis between Persian, Turkic, and Islamic traditions. This blend would influence later states in the region, including the Timurid Empire.

Urban Development: Many cities that flourished under Khwarazmian rule, such as Samarkand and Bukhara, remained important centers of Islamic culture and learning, eventually recovering from the Mongol destruction. The architectural styles developed during this period influenced subsequent building traditions.

Khwarazmian Diaspora: Following the empire's collapse, Khwarazmian military elites dispersed across the Middle East, with some establishing significant positions in Ayyubid Egypt and other states. These Khwarazmian mercenaries influenced military practices in Egypt and the Levant for decades.

Historical Lessons: The empire's rapid collapse serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of diplomatic miscalculation and the importance of accurate intelligence about potential adversaries. Military historians continue to study the Mongol-Khwarazmian war as a classic example of how superior strategy and mobility can overcome numerical disadvantages.

Linguistic and Cultural Heritage: Elements of Khwarazmian culture persist in the diverse heritage of modern Central Asian nations, particularly Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The Khwarazmian-Turkic language, though extinct, represents an important link in the development of Turkic languages in the region.

The Khwarazmian Language and Literature

The Khwarazmian language was a member of the Eastern Iranian language family and served as an important cultural medium alongside Persian and Turkic. Though it eventually became extinct following the Mongol invasions and subsequent Turkification of the region, fragments survive in medieval texts and glossaries.

Notable works produced during the Khwarazmian period include the "Muqaddimat al-Adab" by al-Zamakhshari, a lexicographical work that preserved many Khwarazmian words. Other literary productions of the period demonstrate the sophisticated cultural milieu, with poetry in both Persian and Turkic languages flourishing at the Khwarazmian court.

Environmental Impact

The environmental impact of the Mongol destruction of the Khwarazmian Empire was profound and long-lasting. The destruction of irrigation systems that had been maintained for centuries led to desertification in some areas. Agricultural productivity in regions like Khorasan and Transoxiana did not fully recover for generations.

Some historians have suggested that this environmental degradation contributed to Central Asia's gradual economic decline relative to other parts of the Islamic world in subsequent centuries, though this remains a debated point among scholars.

Archaeological Discoveries

Recent archaeological work has shed new light on life in the Khwarazmian Empire. Excavations at sites like Kunya-Urgench in modern Turkmenistan and Gonur Tepe have revealed sophisticated urban planning, advanced water management systems, and evidence of extensive trade networks.

Urban Centers and Architecture

Particularly notable are the architectural remains of the period, including the mausoleum of Sultan Tekesh in Kunya-Urgench, which showcases the distinctive Central Asian Islamic architectural style that reached its apex under the Khwarazmians. Artifacts recovered from these sites include fine ceramics, metalwork, and textiles that demonstrate the high level of craftsmanship achieved during this period.

Recent excavations at Urgench have uncovered a sophisticated water supply system with ceramic pipes, public baths, and elaborate drainage networks. These findings confirm historical accounts of the city's size and sophistication before its destruction.

Material Culture and Trade

Archaeological evidence has revealed the extent of Khwarazmian trade connections. Chinese porcelain, Baltic amber, and even European artifacts have been found in Khwarazmian sites, confirming historical accounts of their extensive commercial networks. Locally produced ceramics show technical sophistication and artistic influences from both East and West.

Numismatic evidence has been particularly valuable, with Khwarazmian coins found across a vast area from Eastern Europe to China. Analysis of these coins reveals information about economic conditions, metallurgical techniques, and political transitions within the empire.

Ongoing Research

The past decade has seen increased international interest in Khwarazmian archaeological sites. Uzbek-French expeditions at Mizdakhan, Kazakh-American work in the Syr Darya delta, and Turkmen-British investigations at Merv are all contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the empire's material culture and daily life.

Remote sensing technologies are revealing previously unknown structures and settlement patterns. Satellite imagery has identified potential irrigation networks and fortress systems that are only now being correlated with historical accounts of the empire's infrastructure.

The Khwarazmian Empire in Modern Perspective

Today, the Khwarazmian Empire receives growing attention from historians seeking to understand the complex dynamics of medieval Central Asia. Its story challenges simplistic narratives about the region's history and highlights the importance of Central Asia as a crossroads of civilizations.

Historiographical Debates

Modern scholarship has begun to reassess traditional narratives about the Khwarazmian Empire. Some historians have questioned the portrayal of Muhammad II as merely incompetent, suggesting instead that his strategic options were limited by political constraints and the unprecedented nature of the Mongol threat.

Others have emphasized the internal tensions within the empire, particularly between Persian bureaucratic traditions and Turkic military power, as factors contributing to its vulnerability. The relationship between the Shah and his mother, Terken Khatun, has received special attention as an example of how court politics affected strategic decision-making.

National Identity and Cultural Heritage

In modern Central Asian republics, particularly Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, the Khwarazmian period is increasingly celebrated as part of national heritage. Museums in Khiva, Bukhara, and Samarkand highlight Khwarazmian artifacts and architectural achievements.

Cultural festivals, academic conferences, and educational initiatives focused on the Khwarazmian period have proliferated since the 1990s. This renewal of interest reflects both scholarly trends and the search for pre-Soviet historical identities in Central Asian nations.

Tourism and Cultural Preservation

Sites associated with the Khwarazmian Empire have become important destinations on the growing Central Asian tourist circuit. UNESCO World Heritage designations for cities like Bukhara and architectural monuments like the mausoleum of Tekesh have spurred preservation efforts and international interest.

Digital reconstruction projects have allowed visitors and scholars to visualize Khwarazmian cities as they appeared before the Mongol destruction. These initiatives combine archaeological evidence with historical descriptions to create compelling representations of the empire at its height.

The empire's history also offers valuable insights into state formation, the challenges of governing diverse populations, and the relationship between commerce and power in pre-modern societies. As interest in Central Asian history continues to grow, the Khwarazmian Empire's place in the historical narrative is being rightfully reassessed and elevated.

Climate and Geography: Shaping the Khwarazmian Experience

The Khwarazmian Empire developed in a region defined by stark geographical contrasts. The fertile river valleys of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya provided the agricultural basis for urban civilization, while surrounding deserts and steppes shaped defense strategies and facilitated connections with nomadic peoples.

Adapting to Environmental Challenges

The empire's engineers demonstrated remarkable ingenuity in water management. Archaeological evidence reveals complex canal systems, water-lifting devices, and underground water channels (qanats) that allowed agriculture to flourish in this arid environment. The strategic importance of these water systems is underscored by the Mongols' targeting of irrigation infrastructure during their invasion.

Climate fluctuations during the 12th and early 13th centuries may have influenced the empire's development. Some paleoclimatic research suggests that this period saw relatively favorable conditions in Central Asia, with adequate rainfall supporting agricultural expansion. This environmental window of opportunity may have contributed to the empire's rapid rise, just as changing conditions later compounded its collapse.

The rise and fall of the Khwarazmian Empire represents one of history's most dramatic imperial trajectories. From humble beginnings as a provincial governorship to becoming a major power that controlled vast territories, and then collapsing spectacularly in the face of the Mongol onslaught, the empire's story encapsulates the volatility of political fortunes in medieval Central Asia.

Despite its relatively brief existence, the Khwarazmian Empire left an indelible mark on the region's cultural, economic, and political landscape. Its legacy lives on in the architectural monuments, cultural traditions, and historical memory of modern Central Asian nations. By studying this often-overlooked empire, we gain valuable insights into a pivotal period in world history when Central Asia stood at the crossroads of global power and cultural exchange.

For travelers, scholars, and history enthusiasts alike, the remnants of the Khwarazmian Empire offer a fascinating window into a sophisticated civilization that once thrived along the ancient Silk Road, reminding us of Central Asia's central role in the development of human civilization. As archaeological work continues and access to primary sources improves, our understanding of this remarkable empire will only deepen, shedding further light on a crucial chapter in world history that deserves far greater recognition.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚