The Hittite Empire: Forgotten Superpower of the Ancient World

Explore the remarkable rise and enduring legacy of the Hittite Empire, one of antiquity's most influential yet often overlooked civilizations. This comprehensive analysis examines how this Anatolian kingdom emerged to rival Egypt and Babylon, pioneering innovations in diplomacy, military tactics, and governance that shaped the ancient Near East and beyond.

EMPIRES/HISTORYEDUCATION/KNOWLEDGEHISTORY

Kim Shin

4/14/202511 min read

The Hittite Empire stands as one of history's most influential yet often overlooked ancient civilizations. Emerging from the heart of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) around 1650 BCE, this formidable kingdom grew to rival the mighty Egyptian and Babylonian empires, leaving an indelible mark on the ancient Near East. Their innovations in diplomacy, military tactics, and governance created ripples that extended far beyond their territorial boundaries, influencing civilizations for centuries to come.

Origins and Early Development

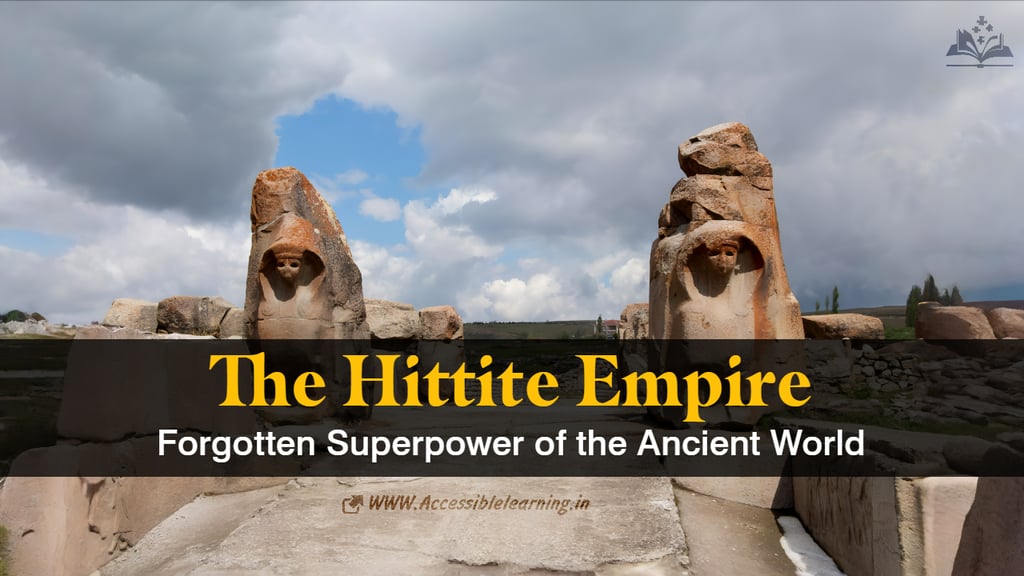

The Hittites established their first capital at Hattusa (near modern Boğazkale, Turkey), building upon the foundations of earlier Anatolian cultures. Archaeological evidence suggests that Indo-European migrants integrated with local Hattic populations, creating a unique cultural synthesis that would become the hallmark of Hittite civilization.

The early Hittite state emerged during a period of significant political fragmentation in Anatolia. Under the leadership of King Hattusili I (c. 1650-1620 BCE), the Hittites began their expansion from a relatively small city-state to a regional power. Hattusili's military campaigns extended Hittite influence southward into northern Syria, bringing the kingdom into direct contact with the older civilizations of Mesopotamia.

Linguistic analysis suggests that the Hittites referred to themselves as "Neshites," after the city of Kanesh (Nesha), indicating that this location may have played a crucial role in their early development before the establishment of Hattusa as their capital. Archaeological excavations at Kültepe (ancient Kanesh) have revealed extensive trading networks operating in the region prior to the rise of the Hittite state, suggesting that economic foundations preceded political consolidation.

The Old Kingdom Period

The Old Kingdom period (c. 1650-1400 BCE) represented the first phase of Hittite imperial development. During this era, the foundations of Hittite administrative and political structures were established. King Mursili I, Hattusili's grandson, demonstrated the growing ambition of the Hittite state by leading a daring military expedition nearly 1,000 kilometers from Hattusa to capture Babylon around 1595 BCE.

This period was characterized by internal struggles for power, with several kings falling victim to palace conspiracies. These internal conflicts eventually weakened the centralized authority of the Hittite state, leading to a brief period of decline.

The Edict of Telepinu, issued around 1500 BCE, attempted to address the problem of royal succession that had plagued the early Hittite state. This remarkable document established clear rules for succession and limited the power of the royal family to eliminate potential rivals. It represents one of the earliest known attempts to create a constitutional framework for governance in the ancient world.

Imperial Resurgence: The New Kingdom

The Hittite Empire entered its most prosperous and powerful phase during the New Kingdom period (c. 1400-1180 BCE). Under the leadership of kings like Suppiluliuma I, Mursili II, and Hattusili III, the empire expanded dramatically, establishing control over much of Anatolia and northern Syria.

Suppiluliuma I (c. 1350-1322 BCE) truly transformed the Hittite state into an empire through military conquest and diplomatic ingenuity. His reign marked the beginning of direct competition with Egypt for control of territories in the Levant. The strategic marriage alliances he arranged with neighboring kingdoms demonstrated the sophisticated diplomatic approach that became a hallmark of Hittite international relations.

Historical records reveal a fascinating diplomatic exchange between Suppiluliuma and the widow of Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun. In what historians call the "Zannanza affair," the Egyptian queen (likely Ankhesenamun) requested that Suppiluliuma send one of his sons to become her husband and the new pharaoh of Egypt. Though Suppiluliuma eventually agreed and sent his son Zannanza, the prince was murdered en route to Egypt, leading to heightened tensions between the two powers.

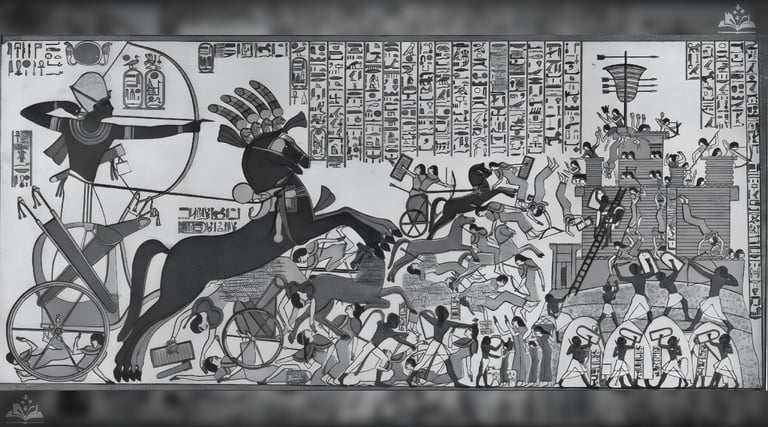

The Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE between the Hittites under King Muwatalli II and the Egyptians under Ramesses II represents one of history's earliest well-documented large-scale battles. The conflict ended in what modern historians consider a strategic stalemate, leading eventually to one of the world's first recorded peace treaties in 1258 BCE. This treaty, preserved in both Egyptian hieroglyphics and Hittite cuneiform, included provisions for mutual defense, extradition of political refugees, and a pledge of eternal peace between the two powers.

Governance and Society

The Hittite Empire functioned as a territorial state with a complex administrative structure. At its center stood the king, who served not only as military leader and chief administrator but also as the supreme religious authority—the "Priest of the Sun Goddess of Arinna."

The Hittite approach to governing conquered territories was notably pragmatic. Unlike some contemporaneous empires that ruled through direct control, the Hittites often established vassal relationships, allowing local rulers to maintain authority while swearing loyalty to the Hittite king. This flexible system of governance helped the empire maintain control over culturally diverse regions.

Hittite society was stratified but showed surprising elements of legal egalitarianism for its time. The legal code, dating from about 1650-1500 BCE, included provisions protecting various social classes, including slaves. Punishments were often more lenient than those found in other contemporary legal systems, emphasizing compensation rather than retribution.

The pankus, often translated as "assembly," represented another distinctive feature of Hittite governance. While its exact nature remains debated, this institution appears to have served as a council of nobles that could, in certain circumstances, check royal power. Some texts suggest that the pankus could even participate in judgments against members of the royal family who had committed serious crimes.

Gender Roles and Family Structure

Hittite society demonstrated relatively progressive attitudes toward gender roles compared to many contemporary civilizations. The tawananna, or queen, maintained significant political and religious authority even after her husband's death, often continuing to exercise influence during her son's reign. Queens like Puduhepa, wife of Hattusili III, participated actively in diplomatic correspondence with other great powers and affixed their seals alongside the king's on official documents.

Marriage contracts and other legal texts reveal that Hittite women could own property independently, initiate divorce proceedings, and engage in business transactions. While patriarchal structures certainly existed, the legal rights afforded to women surpassed those found in many other ancient Near Eastern societies.

Family structure centered around the nuclear family unit, with inheritance typically passing from father to son. However, adoption practices were formalized and common, providing flexibility in family composition and succession arrangements within both royal and non-royal contexts.

Economic Systems

The Hittite economy combined agricultural production with extensive trade networks and specialized craft production. The empire's location at the crossroads of major trade routes provided significant economic advantages, allowing the Hittites to control the flow of goods between Mesopotamia, the Aegean, and the Black Sea regions.

Agricultural production formed the backbone of the economy, with barley, wheat, and legumes as primary crops. Textile production, particularly wool processing, constituted a major industry, with evidence of standardized production methods and quality control measures. Metallurgy, especially bronze and later iron working, represented another crucial economic sector that contributed to both military power and export revenues.

The palace economy played a central role, with the royal administration collecting and redistributing agricultural surpluses through a complex system of storage facilities throughout the empire. Temple complexes also functioned as significant economic institutions, managing extensive landholdings and workshops.

Cultural and Technological Achievements

The Hittites were remarkable cultural synthesizers, absorbing and adapting elements from the many civilizations with which they came into contact. Their religious pantheon incorporated deities from Hurrian, Mesopotamian, and local Anatolian traditions. They conducted elaborate festivals throughout the year, many lasting several days and involving the king's participation.

Technologically, the Hittites were innovators in metallurgy, particularly in ironworking. While they did not invent iron smelting as once believed, they did develop advanced techniques for working with this metal, which contributed to their military advantages. Recent archaeological evidence suggests that the Hittites mastered complex iron-working techniques, including carburization (the addition of carbon to iron), creating early forms of steel.

Their linguistic contributions were equally significant. The Hittites used a cuneiform script adapted from Mesopotamia to write their Indo-European language. The decipherment of Hittite in the early 20th century provided crucial insights into the early development of Indo-European languages.

The Hittites maintained an extensive literary tradition, including myths, prayers, ritual texts, and historical annals. The "Telipinu Myth," which explains the disappearance and return of a fertility deity, demonstrates sophisticated narrative techniques and provides insights into religious beliefs. Historical texts, such as the "Annals of Mursili II," document military campaigns and political events with remarkable attention to chronological detail and causation.

Artistic Expressions

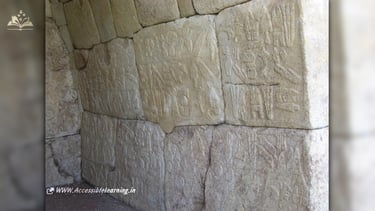

Hittite art blended indigenous Anatolian elements with influences from Mesopotamia, Syria, and the Aegean. Rock reliefs, such as those at Yazılıkaya and İvriz, represent some of the most impressive examples of Hittite artistic expression. These monumental carvings typically depict royal figures, deities, or ritual scenes.

Sculpture in the round was less common but includes impressive examples like the ceremonial gates at Hattusa, guarded by lions and sphinxes. These monumental sculptures combined artistic expression with practical architectural functions and religious symbolism.

Metalwork represented another important artistic medium, with gold, silver, and bronze objects demonstrating sophisticated craftsmanship. Ritual vessels, jewelry, and ceremonial weapons often featured relief decoration depicting religious scenes or symbolic motifs.

Seal stones, used to mark documents and property, provide examples of miniature art with intricate carving. Royal seals typically featured hieroglyphic inscriptions naming the king or queen, while other designs incorporated mythological creatures or symbolic scenes.

Military Innovation

Military prowess formed the backbone of Hittite imperial power. Their armies incorporated a three-man chariot design that proved highly effective on the battlefield. Each chariot carried a driver, a shield-bearer, and a warrior, creating a mobile fighting platform that could execute complex tactical maneuvers.

The Hittites also demonstrated remarkable skill in siege warfare, developing techniques to capture fortified cities throughout Anatolia and Syria. Their military innovations extended to organizational structure, with a professional officer corps and logistical systems that supported campaigns far from the imperial heartland.

Military intelligence played a crucial role in Hittite strategy. The empire maintained an extensive network of spies and informants throughout neighboring territories. Written reports to the king detailed troop movements, fortress defenses, and political developments, allowing for strategic planning based on accurate information.

Military service obligations were systematically organized through the "sahhan and luzzi" system, which required various categories of subjects to provide either direct military service or support services and supplies to the army. Land grants to military officers, known as "gish-tukul land," created a class of professional warriors with direct ties to the crown.

Religious Beliefs and Practices

The Hittite religious system encompassed "a thousand gods," reflecting both their indigenous beliefs and their assimilation of deities from conquered territories. The weather god Tarhunt and the sun goddess of Arinna stood at the pantheon's apex, representing male and female divine power, respectively.

Religious rituals permeated daily life, from state festivals to household practices. The religious calendar included numerous festivals, some lasting several days or even weeks. Many of these ceremonies required the personal participation of the king and queen as chief religious officials, demonstrating the inseparable nature of political and religious authority.

Divination practices, including hepatoscopy (liver divination), ornithomancy (bird divination), and the interpretation of dreams, played central roles in decision-making processes. Before major military campaigns or political decisions, multiple forms of divination might be performed to ensure divine approval.

The concept of divine anger and its ritual amelioration appears frequently in Hittite religious texts. When misfortune struck the land, elaborate rituals of confession, purification, and offering sought to identify and address the causes of divine displeasure. These "plague prayers," particularly those attributed to Mursili II during a devastating epidemic, reveal sophisticated theological reasoning about collective guilt and divine justice.

Collapse and Legacy

Around 1180 BCE, the Hittite Empire collapsed rather suddenly. Multiple factors likely contributed to this downfall, including invasions by the mysterious "Sea Peoples," climate change that may have led to agricultural failures, internal political instability, and possibly pandemic diseases.

Recent paleoclimatic research has provided evidence of a severe drought throughout the eastern Mediterranean region around the time of the empire's collapse. This climate crisis would have undermined agricultural production, triggering food shortages and population movements that destabilized the entire political system.

Archaeological evidence from Hattusa indicates that the capital was systematically abandoned rather than violently destroyed. The royal archives were left in place, suggesting an organized withdrawal rather than a panicked flight. This pattern suggests that the final collapse may have unfolded gradually, with the central administration attempting to maintain control even as its resource base eroded.

Following the empire's collapse, several Neo-Hittite states emerged in northern Syria and southeastern Anatolia, preserving elements of Hittite culture and political traditions for several centuries. These successor states maintained distinctive art styles and hieroglyphic writing systems derived from Late Hittite traditions.

The Neo-Hittite kingdoms, including Carchemish, Tabal, and Que, continued to use Luwian hieroglyphics for monumental inscriptions until approximately 700 BCE. These states engaged in complex relationships with the rising power of Assyria, sometimes serving as vassals, sometimes as opponents, and occasionally as cultural intermediaries transmitting Hittite traditions to the greater Near East.

The true legacy of the Hittites extends far beyond these immediate successors. Their diplomatic innovations, including formal written treaties between equal powers, established precedents that would influence international relations for millennia. Their legal traditions demonstrated a surprisingly nuanced approach to justice for their era. Perhaps most importantly, the rediscovery of the Hittites in the late 19th and early 20th centuries transformed our understanding of ancient Near Eastern history, filling a crucial gap in the historical record.

Archaeological Discoveries and Modern Research

Modern understanding of the Hittites began with the excavations at Boğazkale (ancient Hattusa) in the late 19th century. The discovery of the royal archives, containing thousands of clay tablets, provided unprecedented insight into Hittite administration, diplomacy, and daily life. Ongoing archaeological work continues to reveal new dimensions of this fascinating civilization.

The rock sanctuary at Yazılıkaya near Hattusa represents one of the most impressive religious monuments of the ancient world. Its relief carvings depict processions of deities, providing a visual catalog of the Hittite pantheon and offering rare insights into their religious practices. Recent research suggests that the site may have also functioned as a sophisticated lunar calendar, demonstrating advanced astronomical knowledge.

Excavations at sites like Alacahöyük, Ortaköy (ancient Sapinuwa), and Kuşaklı (ancient Sarissa) have revealed provincial centers with distinctive architectural features and artifact assemblages. These excavations demonstrate the regional diversity within the empire and illuminate the relationships between the capital and provincial territories.

Advances in paleogenetics have begun to shed light on the population history of ancient Anatolia. Recent DNA analyses of human remains from Hittite-period sites indicate a complex genetic landscape, with evidence of both continuity with earlier Anatolian populations and admixture with groups from the Caucasus and the Eurasian steppe, consistent with the hypothesis of Indo-European migration.

Interdisciplinary research combining archaeology, textual analysis, and environmental science has enhanced understanding of the Hittites' agricultural systems and their relationship with their environment. Evidence suggests sophisticated water management techniques, including dams, reservoirs, and irrigation systems, that helped support dense populations in the semi-arid central Anatolian plateau.

Digital humanities approaches, including 3D modeling of archaeological sites and advanced imaging techniques for cuneiform tablets, have created new opportunities for analyzing and preserving Hittite cultural heritage. These technologies allow for virtual reconstruction of damaged monuments and improved readings of previously illegible texts.

The Hittites in Modern Geopolitical Context

The legacy of the Hittites continues to resonate in modern Turkey, where they are recognized as one of the earliest complex civilizations to develop in Anatolia. Archaeological sites like Hattusa attract thousands of tourists annually and have been designated UNESCO World Heritage sites, acknowledging their global cultural significance.

Academic research on the Hittites involves international collaboration among scholars from Turkey, Europe, North America, and Japan. These collaborative projects not only advance historical understanding but also contribute to cultural diplomacy and heritage preservation.

The Hittite textual corpus, with its detailed treaties, legal codes, and historical narratives, provides valuable case studies for modern diplomatic and legal studies. The emphasis on formal written agreements between equal powers and the sophisticated understanding of interstate relations demonstrated in these texts continues to offer insights relevant to contemporary international relations.

The Hittite Empire represents a remarkable chapter in human history—a civilization that rose from relative obscurity to challenge the established powers of the ancient world, creating innovative solutions to the challenges of governance, diplomacy, and warfare. Their achievements echo through time, reminding us that history's great innovations often emerge from unexpected places.

As archaeological research continues and new analytical techniques develop, our understanding of the Hittites continues to deepen, revealing an increasingly complex picture of this sophisticated civilization that helped shape the course of ancient history in the Near East and beyond. The study of the Hittites demonstrates how ancient societies navigated challenges strikingly similar to those we face today: climate change, intercultural relations, technological innovation, and the maintenance of complex political systems. In this sense, the Hittite experience offers not just fascinating historical insight but potentially valuable lessons for our contemporary world.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚