Obon Festival: Honoring Spirits, Family, and Tradition in Japan!

Explore the Obon Festival of Japan—a deeply spiritual celebration honoring ancestors with lanterns, traditional dances, rituals, and family reunions. Discover its history, customs, travel tips, and modern significance.

CULTURE/TRADITIONTRAVEL LIFECELEBRATION/FESTIVALSJAPAN

Kim Shin

8/8/20255 min read

The Obon Festival, also known simply as Obon or Bon, is one of Japan’s most spiritually significant and culturally vibrant events. Celebrated with deep reverence, Obon is a Buddhist-Confucian custom observed to honor the spirits of one's ancestors. It is a time when families come together, graves are cleaned, lanterns are lit, and traditional dances illuminate the summer nights.

This article explores the origins, customs, symbolism, regional variations, and modern-day relevance of Obon in Japan and beyond.

What is the Obon Festival?

Obon (お盆) is a traditional Japanese festival that commemorates deceased ancestors and welcomes their spirits back to the world of the living for a brief period. Rooted in Buddhist beliefs, Obon blends ritual, folklore, and family reunion. The word “Obon” comes from the Sanskrit “Ullambana,” which means “hanging upside down” and refers to the suffering of spirits in the afterlife.

Dates: Obon is usually celebrated from August 13 to 16, although some regions observe it in mid-July.

Significance: It’s a time to reflect on familial heritage, express gratitude, and perform rituals that help ancestral spirits rest in peace.

The Origins & Evolution of Obon

Obon traces its roots to a Buddhist story about Mokuren, a disciple of Buddha who used supernatural powers to see his deceased mother suffering in the Realm of Hungry Ghosts. Through Buddha’s teachings, Mokuren offered food to monks and danced with joy when his mother was freed from suffering—thus giving birth to Bon Odori, the traditional dance of Obon.

Over centuries, Obon evolved by integrating Shinto ancestral worship and regional folklore. While its core remains spiritual, Obon is also a celebration of life, family, and seasonal harmony.

Key Rituals & Traditions of Obon

Mukaebi & Okuribi (Welcome and Farewell Fires)

Mukaebi (迎え火): Small fires are lit at the entrances of homes on August 13 to guide spirits back.

Okuribi (送り火): On August 16, fires are again lit to guide spirits back to the afterlife.

In Kyoto, this farewell fire culminates in the spectacular Daimonji Gozan Okuribi, where massive kanji characters are set ablaze on mountainsides.

Cleaning of Graves (Ohaka-mairi)

Families visit ancestral graves to clean tombstones, offer flowers, incense, and food, and spend reflective moments honoring their lineage.

Floating Lanterns (Tōrō Nagashi)

Paper lanterns with candles are floated down rivers or set afloat in lakes to symbolize the spirits’ return to the spirit world. This mesmerizing ritual is practiced in areas like Hiroshima and Asakusa.

Bon Odori (盆踊り) Dance

Communities gather in parks and temples to perform traditional folk dances, often wearing colorful yukata (summer kimono). The dances vary regionally, but they all share a rhythmic, circular movement that symbolizes the cycle of life.

Offerings at Home Altars (Butsudan)

Houses display ancestral altars with offerings of fruits, rice, tea, and favorite items of the deceased. The rituals are usually led by the family’s elder members.

Obon in Modern Times and Global Communities

While Japan has modernized, Obon remains deeply respected—even among younger generations. It also serves as one of the country’s biggest holiday seasons, similar to Thanksgiving or Christmas in the West.

In places with Japanese diaspora—like Hawaii, Brazil, and the U.S. mainland—Obon is celebrated with community festivals, food stalls, and Bon Odori, keeping the tradition alive across borders.

Modern adaptations include:

Virtual Obon celebrations (post-COVID)

Eco-friendly lanterns and digital offerings

Festive events combining dance, music, and food

Spiritual Symbolism and Human Connection

Beyond rituals, Obon is a gentle reminder of impermanence (mujō) and the interconnectedness of past, present, and future. It teaches:

Gratitude: for those who came before us.

Reflection: on life’s cyclical nature.

Connection: with family and community.

Even non-religious participants often find themselves emotionally moved during this time.

Quick Facts: Obon Festival at a Glance

Type: Cultural, spiritual

Observed In: Japan and Japanese communities worldwide

Main Dates: August 13–16 (varies regionally)

Key Elements: Fire rituals, grave visits, Bon dances, lanterns

Symbolism: Ancestral reverence, family unity, life-death cycle

FAQs

Q. Is Obon a public holiday in Japan?

No, Obon is not a national public holiday, but many businesses close, and workers take leave during this period.

Q. What do you wear to Obon festivals?

Most people wear yukata, a casual summer kimono. However, modern attire is also acceptable, especially for tourists.

Q. Can foreigners participate in Obon?

Absolutely. Foreigners are welcome to observe, join Bon Odori, and learn about the traditions—respectfully, of course.

Q. Is Obon similar to Día de los Muertos?

In a way, yes. Both honor deceased loved ones, involve altars and offerings, and celebrate with community gatherings.

Q. What food is eaten during Obon?

Traditional vegetarian offerings, mochi, seasonal fruits, and festival foods like takoyaki and yakisoba are popular.

Obon is more than just a cultural celebration—it's a heartfelt expression of remembrance, gratitude, and renewal. Whether you’re lighting a lantern, joining a Bon dance, or simply reflecting on your own roots, the spirit of Obon invites us all to pause and honor the journey of life.

Travel Tips for Experiencing the Obon Festival in Japan

Plan Your Trip Early

Obon is one of the busiest travel periods in Japan, comparable to Golden Week and New Year holidays. Expect:

Sold-out trains and flights

Fully booked hotels

Heavy traffic on roads

Tip: Book accommodations, JR Pass, and local tours at least 2–3 months in advance.

Join a Local Bon Odori Festival

Look for community Bon Odori events in public parks, shrines, or temples. Popular locations include:

Koenji Awa Odori (Tokyo)

Gujo Odori (Gifu)

Higashi Hongan-ji Temple (Kyoto)

Tip: Wear a yukata and rent it from local shops to blend into the festivities and feel the cultural vibe.

Visit Cemeteries Respectfully

If visiting a cemetery or family graveyard:

Dress modestly.

Do not touch offerings.

Be quiet and respectful—this is a sacred act of remembrance.

Try Traditional Obon Foods

Look for local dishes often made as offerings and served during the festival:

Inarizushi (sushi in fried tofu)

Mochi (rice cakes)

Nasu no Yaki (grilled eggplant)

Seasonal fruits

Some regions also serve special vegetarian temple cuisine (shōjin ryōri) during Obon.

Witness the Lantern Floating Ceremony (Tōrō Nagashi)

Some of the most beautiful locations:

Asakusa, Tokyo – Sumida River

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

Kumamoto’s Suizenji Park

Tip: Arrive early to secure a good spot, and consider joining the lantern floating by reserving a lantern in advance (especially in Hiroshima).

Respect the Spiritual Atmosphere

Obon is not just a festival—it's a time of mourning and reverence. Avoid loud or disruptive behavior during ceremonies and at temples.

Check the Region’s Celebration Dates

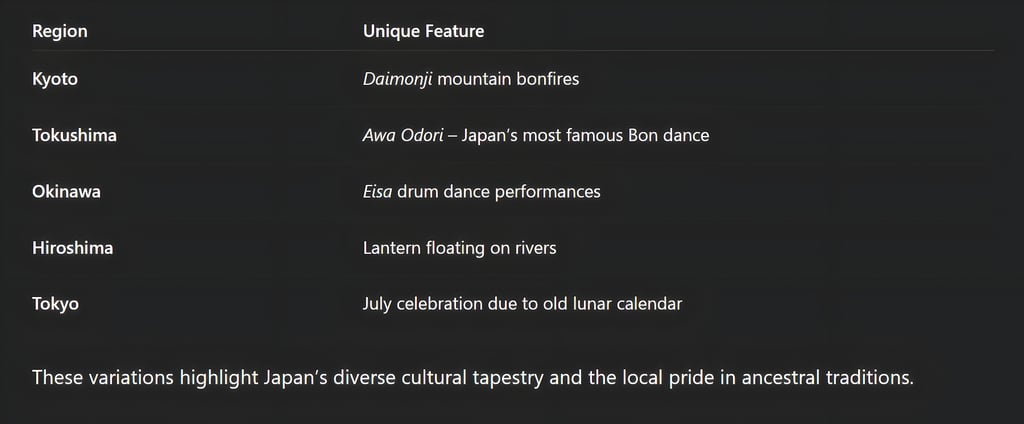

Different parts of Japan celebrate Obon at different times:

Mid-July (Old Calendar) – Tokyo, Kanagawa

Mid-August (New Calendar) – Kyoto, Osaka, most of Japan

Late August (Okinawa)—Eisa Dance events

Interesting Facts About the Obon Festival

Dancing for the Dead

The Bon Odori dances originated from joyful gratitude after a monk saved his mother's spirit. Today, the dances differ by region and are meant to entertain and honor the returning spirits.

Spirit Animals Made from Vegetables

Some households create symbolic animals called “Shōryō-uma”:

Cucumber horse – Helps spirits arrive quickly.

Eggplant cow – Helps spirits return slowly, enjoying their stay.

These are often placed on home altars with chopstick “legs.”

The Fire Ritual in Kyoto is Visible for Miles

The Daimonji Gozan Okuribi event in Kyoto uses giant fires shaped like kanji characters—like 大 (meaning “great”)—to send spirits back. It’s visible from many parts of the city and draws thousands of spectators.

It’s Not a National Holiday—But It Feels Like One

Despite Obon not being a public holiday, it causes mass closures of companies and schools as families travel back to their hometowns. Major cities like Tokyo often become quieter during this time.

A Time for Family Reunions

Obon is one of the rare times when three or four generations may gather under one roof. It strengthens familial bonds and cultural continuity.

Obon is Celebrated Worldwide

From Honolulu to São Paulo, Japanese communities across the globe observe Obon with music, dancing, and lantern festivals. The largest Obon outside Japan is held in Hawaii, known for its grand Bon Odori and temple services.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚