Lack of Access to Quality Education in Africa: Challenges, Data, and Pathways Forward

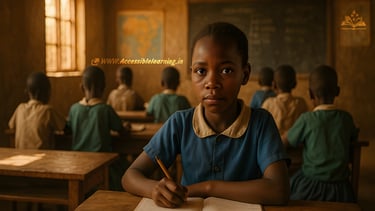

Explore the barriers to quality education in Africa, the latest 2024-2025 data, gender disparities, economic impacts, and innovative solutions transforming learning access across the continent.

AFRICAABUSE/VIOLENCEAWARE/VIGILANT

Kim Shin

10/10/202515 min read

Access to quality education remains one of the most pressing developmental challenges facing the African continent. While significant progress has been made in expanding educational enrollment over the past two decades, profound disparities persist in the quality, equity, and accessibility of learning opportunities across the region. This comprehensive analysis examines the multifaceted barriers preventing millions of African children and youth from receiving adequate education, explores the latest data on educational outcomes, and evaluates potential solutions to bridge these critical gaps.

Understanding the Scale of the Educational Crisis

The educational landscape in Africa presents a complex picture of both advancement and persistent inequality. According to UNESCO Institute for Statistics data from 2024, approximately 98 million children and adolescents across sub-Saharan Africa remain out of school, representing nearly one-third of the global out-of-school population. This figure encompasses roughly 30 million primary school-age children, 21 million lower secondary-age adolescents, and 47 million upper secondary-age youth who have never entered a classroom or have dropped out before completing their education.

The situation extends beyond mere enrollment numbers to encompass fundamental questions about educational quality and learning outcomes. The World Bank's 2024 Human Capital Index reveals that children born in sub-Saharan Africa today will achieve only 40 percent of their potential productivity as future workers when compared to a benchmark of complete education and full health. This statistic underscores how inadequate education perpetuates cycles of poverty and limits economic development across generations.

Regional disparities within Africa itself add another layer of complexity to the educational crisis. West and Central Africa face particularly acute challenges, with countries like Niger, South Sudan, and Burkina Faso recording some of the lowest school attendance rates globally. Meanwhile, North African nations and countries like Kenya, Rwanda, and Botswana have made substantial strides in improving educational access and quality, demonstrating that progress is achievable with appropriate policy interventions and resource allocation.

Primary Barriers Preventing Access to Quality Education

The obstacles preventing African children from receiving adequate education operate on multiple interconnected levels, ranging from systemic infrastructure deficits to cultural and economic factors that shape individual family decisions about schooling.

Infrastructure inadequacy represents perhaps the most visible barrier to educational access. Across rural Africa, millions of children live more than five kilometers from the nearest school, a distance that becomes prohibitive when combined with poor road conditions, safety concerns, and the physical demands on young learners. The African Union's Continental Education Strategy for Africa reports that approximately 60 percent of schools in rural sub-Saharan Africa lack basic amenities, including electricity, clean water, and adequate sanitation facilities. This infrastructure deficit creates environments that are not conducive to learning and disproportionately affects girls, who face additional challenges related to menstrual hygiene management in schools without proper facilities.

Teacher shortages and inadequate educator training compound infrastructure problems throughout the continent. UNESCO estimates that sub-Saharan Africa will need to recruit approximately 15 million additional teachers by 2030 to achieve universal primary and secondary education. The current reality sees classroom sizes regularly exceeding 60 students per teacher in many regions, making individualized instruction impossible and compromising learning quality for all students. Beyond sheer numbers, teacher qualification levels present another concern, with significant percentages of educators lacking formal pedagogical training or subject matter expertise, particularly in science, mathematics, and technology disciplines.

Economic barriers create insurmountable obstacles for families living in poverty. Although many African nations have eliminated official primary school fees, indirect costs, including uniforms, textbooks, transportation, and examination fees, place education beyond the reach of the most vulnerable populations. The African Development Bank notes that households in the poorest quintile across sub-Saharan Africa allocate disproportionate shares of their income to educational expenses, often forcing difficult choices between schooling and immediate survival needs. This economic pressure contributes significantly to high dropout rates, particularly during transitions between educational levels when costs typically increase.

Gender inequality manifests as both a cause and consequence of limited educational access throughout Africa. Cultural norms in many communities prioritize boys' education over girls' schooling, viewing female education as less economically valuable or culturally appropriate. Early marriage and pregnancy remain leading causes of school dropout among adolescent girls, with UNICEF data from 2024 indicating that approximately 12 million girls are married before age 18 in Africa each year. These young women rarely return to formal education, perpetuating intergenerational cycles of limited literacy and economic opportunity.

Conflict and political instability have devastated educational systems across multiple African nations. Countries experiencing ongoing violence or political upheaval, including the Central African Republic, Mali, Somalia, and parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo, have seen schools deliberately targeted, teachers killed or displaced, and entire generations of children denied educational opportunities. The Education in Emergencies sector reports that conflict-affected areas in Africa account for more than half of the world's out-of-school children, with displaced populations facing particular difficulties accessing quality education in refugee camps or host communities.

Language policies in education create subtle but significant barriers to learning quality across multilingual African societies. Many educational systems continue to use former colonial languages as the primary medium of instruction, despite research consistently demonstrating that children learn most effectively in their mother tongue during early primary years. This linguistic mismatch contributes to high repetition and dropout rates, particularly in rural areas where children may have minimal exposure to the official language of instruction before entering school.

The Quality Deficit in African Education Systems

Beyond access issues, the quality of education provided in many African schools raises serious concerns about whether attending school translates into meaningful learning outcomes. The Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality conducts regular assessments revealing alarming deficits in foundational literacy and numeracy skills among students who have completed several years of schooling.

Learning poverty, defined by the World Bank as the percentage of ten-year-old children unable to read and understand a simple text, affects approximately 89 percent of children in sub-Saharan Africa according to 2024 estimates. This metric starkly illustrates how attendance alone does not guarantee educational achievement when systemic quality issues remain unaddressed. Students may sit in classrooms for years without acquiring the basic skills necessary for further learning or economic participation.

Curriculum relevance presents another dimension of the quality challenge. Many African educational systems continue to operate with curricula that inadequately prepare students for the realities of 21st-century economies and societies. Overemphasis on rote memorization rather than critical thinking, limited integration of technology and digital literacy skills, and insufficient vocational and technical education options leave graduates ill-equipped for available employment opportunities. The African Union's Agenda 2063 emphasizes the need for education that develops innovation, entrepreneurship, and skills aligned with continental development priorities, yet translating these goals into classroom practice remains an ongoing challenge.

Assessment and accountability mechanisms within educational systems often lack the rigor necessary to drive continuous improvement. Many countries conduct limited systematic evaluation of student learning outcomes, teacher performance, or school effectiveness, making it difficult to identify problem areas or measure the impact of interventions. Where assessments do occur, results frequently fail to inform policy adjustments or resource allocation decisions that could address identified deficiencies.

Technology and Digital Divide Implications

The rapid global digitalization of education has created new opportunities but also exacerbated existing inequalities across Africa. The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically highlighted the digital divide when schools closed and instruction moved online, leaving the vast majority of African students without the devices, internet connectivity, or digital literacy necessary to continue learning remotely.

Current statistics paint a sobering picture of digital access across the continent. The International Telecommunication Union reports that only about 33 percent of the African population has internet access, with rates significantly lower in rural areas and among low-income households. Many schools lack electricity, making the integration of digital learning tools impossible even where devices might be available. This digital exclusion threatens to create a generation of African youth unable to compete in increasingly technology-dependent global economies.

However, innovative approaches to educational technology tailored to African contexts offer promising possibilities. Mobile learning platforms that function on basic phones rather than requiring smartphones or computers have expanded access to educational content in several countries. Radio- and television-based distance learning programs reach students in areas without internet connectivity. Solar-powered digital classrooms and offline educational content provide alternatives to conventional technology integration models that assume reliable electricity and internet access.

Gender Disparities and Girls' Education Challenges

The gender dimension of educational access in Africa deserves particular attention given its profound implications for development outcomes. While gender parity in primary education enrollment has improved in many African countries, significant disparities persist at secondary and tertiary levels, and enrollment numbers mask ongoing challenges related to school completion, learning quality, and the barriers girls face within educational settings.

Adolescent girls confront multiple interconnected obstacles that frequently lead to school dropout. Beyond early marriage and pregnancy, many face sexual harassment and gender-based violence in schools or during commutes to educational institutions, creating unsafe environments that deter continued attendance. Traditional household responsibilities disproportionately burden girls with domestic labor and care duties that leave limited time for studying or attending school regularly. During periods of economic hardship, families more frequently withdraw daughters from school while maintaining sons' enrollment, reflecting persistent cultural biases about the value of female education.

The lack of female teachers and role models in many African schools compounds these challenges. Research consistently demonstrates that girls perform better academically and are more likely to complete their education when taught by female educators, yet women remain significantly underrepresented in teaching staff, particularly in rural areas and at secondary levels. Addressing this requires intentional recruitment and support for female teachers, including provisions for safety, housing, and career development in remote postings.

Investment in girls' education generates exceptional returns across multiple development indicators. Educated women have fewer, healthier children, earn higher incomes, participate more actively in decision-making processes within their communities, and ensure their own children attend school. The World Economic Forum estimates that closing the gender gap in education could add trillions of dollars to Africa's cumulative GDP over the coming decades. These compelling economic and social arguments have driven increased policy focus on girls' education, though translating commitment into comprehensive action remains an ongoing process.

Economic Implications of Educational Deficits

The educational crisis in Africa carries profound economic consequences that extend far beyond individual earning potential to affect national productivity, innovation capacity, and regional competitiveness in global markets. The relationship between educational attainment and economic development operates through multiple channels, creating both immediate costs and long-term opportunity losses.

Human capital formation represents the most direct economic impact of educational deficits. When large segments of the population lack basic literacy and numeracy skills, they cannot productively participate in formal economies or adapt to technological changes that increasingly characterize work opportunities. The African Development Bank estimates that low educational levels cost the continent billions of dollars annually in lost productivity and reduced economic output. Countries with higher average educational attainment consistently demonstrate stronger economic growth trajectories, better governance outcomes, and greater resilience to economic shocks.

Youth unemployment and underemployment across Africa partially reflect mismatches between educational outcomes and labor market needs. With approximately 60 percent of Africa's population under 25 years old, the demographic dividend that could drive economic growth instead becomes a liability when young people lack the skills necessary for available jobs or entrepreneurial activities. The International Labour Organization reports that youth unemployment rates in many African countries exceed 20 percent, with even higher rates of vulnerable employment, where young people work in informal, insecure positions with limited prospects for advancement.

Innovation and technological advancement depend fundamentally on educational foundations that develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and technical capabilities. African countries seeking to move beyond primary commodity exports toward value-added production and service industries require workforces with strong educational backgrounds in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. The current educational landscape produces insufficient graduates in these fields to support industrial diversification and technological innovation, limiting economic transformation possibilities.

Agricultural productivity, still central to many African economies, improves substantially when farmers have basic education and literacy. Research demonstrates that literate farmers adopt new techniques more quickly, use resources more efficiently, and achieve higher yields than their less-educated counterparts. Given that agriculture employs the majority of Africa's workforce in many countries, educational investments directly enhance food security and rural economic development.

Innovative Solutions and Successful Interventions

Despite the scale of challenges facing African education systems, numerous innovative approaches and successful interventions demonstrate that progress is achievable through targeted, contextually appropriate strategies. These solutions range from policy reforms to grassroots initiatives that address specific barriers to access and quality.

Community-based school management models have shown remarkable success in improving educational outcomes by increasing local ownership and accountability. Programs that establish school management committees with strong parent and community representation enable context-specific responses to local challenges, whether related to infrastructure needs, teacher attendance, or cultural barriers to girls' education. Rwanda's implementation of this approach has contributed to dramatic improvements in enrollment and completion rates across the country.

Conditional cash transfer programs address economic barriers by providing financial incentives to families who keep children in school. These initiatives, implemented successfully in countries including Kenya, Ghana, and South Africa, typically target the poorest households and often include additional incentives for girls' attendance or completion of specific educational milestones. Evaluation studies demonstrate that well-designed cash transfer programs significantly increase school enrollment and attendance while reducing child labor and early marriage rates.

Alternative education pathways serve children and youth who have missed opportunities for traditional schooling or dropped out before completion. Accelerated learning programs condense primary curricula into shorter timeframes for older children, enabling them to acquire foundational skills and potentially transition into mainstream education systems. Non-formal education initiatives provide flexible scheduling and practical skills training for adolescents and young adults who must balance learning with work or family responsibilities.

Technology-enabled solutions tailored to African contexts are expanding educational access and improving quality despite infrastructure limitations. The Kenyan program M-Shule delivers personalized learning content via SMS to students' mobile phones, requiring no internet connection or smartphone. Solar-powered digital libraries provide access to thousands of books in areas without electricity or physical libraries. Open educational resources and massive open online courses offer high-quality learning materials at minimal cost, though maximizing their impact requires addressing fundamental access barriers.

Teacher professional development initiatives focused on practical pedagogical improvement have demonstrated significant impacts on learning outcomes. Programs that combine initial training with ongoing mentorship and peer learning communities help educators develop more effective teaching strategies, better classroom management skills, and stronger subject knowledge. Finland's partnership with Namibia to strengthen teacher education represents one example of international collaboration supporting sustainable improvements in teaching quality.

Mother-tongue instruction policies that transition gradually to official languages have improved learning outcomes in several African countries. Ethiopia's implementation of mother-tongue education during the first eight years of schooling has contributed to higher achievement levels compared to systems that impose foreign languages from the beginning. This approach respects linguistic diversity while ensuring students eventually acquire proficiency in languages necessary for broader economic participation.

Public-private partnerships leverage resources and expertise from multiple sectors to address educational challenges. Initiatives like the Educate Girls program in Nigeria combine NGO operational capacity with corporate funding and government policy support to increase girls' enrollment in underserved communities. The African Leadership Academy develops future leaders through an innovative curriculum combining academic rigor with leadership training and entrepreneurship skills, demonstrating what is possible when traditional educational models are reimagined.

Policy Frameworks and International Commitments

African governments and international organizations have established ambitious policy frameworks recognizing education's central role in sustainable development. The African Union's Continental Education Strategy for Africa 2016-2025 outlines comprehensive goals for expanding access, improving quality, promoting relevance, and mobilizing resources for education across the continent. This framework emphasizes harmonizing educational systems, integrating traditional and modern knowledge systems, and leveraging technology to overcome infrastructure limitations.

The Sustainable Development Goal 4, which commits nations to ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education for all by 2030, has galvanized increased attention to African educational challenges. However, progress toward this goal remains uneven across the continent, with many countries unlikely to achieve the specified targets without dramatic acceleration of current efforts. The Education 2030 Framework for Action acknowledges that sub-Saharan Africa requires particular support and investment to close existing gaps and achieve universal quality education.

Domestic resource mobilization for education has increased in many African countries, with governments expanding education budget allocations as percentages of both GDP and total government expenditure. However, these increases often prove insufficient given the scale of needs, population growth rates, and competing demands for limited public resources. International financing remains critical, though aid flows to education in Africa have stagnated in recent years, creating funding gaps that threaten progress.

Debt burdens constrain educational investments in many African countries, as governments allocate substantial portions of budgets to debt service rather than social sector development. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these fiscal pressures, with many countries facing difficult choices between maintaining educational services and addressing immediate health and economic crises. Advocacy for debt relief and restructuring emphasizes the need for fiscal space to invest in human capital development, including education.

The Path Forward: Recommendations and Priorities

Addressing Africa's educational access and quality challenges requires comprehensive strategies that tackle multiple barriers simultaneously while building on successful interventions and innovations. Priority actions must occur at international, national, and community levels to create the systemic changes necessary for transformative educational improvement.

Increased and sustained financing represents the most fundamental requirement for educational progress. African governments should work toward allocating at least 20 percent of national budgets to education, as recommended by international frameworks, while ensuring efficient use of resources through improved planning and accountability mechanisms. International donors must honor aid commitments and explore innovative financing mechanisms including education bonds and debt-for-education swaps that free up resources for educational investment.

Teacher recruitment, training, and retention must receive urgent attention through policies that make teaching an attractive profession with adequate compensation, professional development opportunities, and supportive working conditions. Particular emphasis on recruiting and supporting female teachers can address gender disparities while providing role models for girls. Deploying teachers to rural and underserved areas requires incentive structures including housing, hardship allowances, and accelerated career advancement opportunities.

Infrastructure development should prioritize the most basic elements necessary for safe and effective learning environments, including adequate classrooms, water and sanitation facilities, and electricity access. School construction and renovation programs must consider demographic projections to ensure sufficient capacity for growing populations. Infrastructure investments should incorporate energy-efficient and sustainable designs appropriate to local contexts.

Curriculum reform processes should engage diverse stakeholders including educators, employers, parents, and students to develop relevant learning frameworks that balance foundational skills with critical thinking, creativity, and practical competencies. Integration of local languages, cultural knowledge, and African perspectives alongside global knowledge standards can create more meaningful educational experiences for learners. Technical and vocational education expansion provides alternative pathways to economic participation for youth with diverse interests and aptitudes.

Technology integration must proceed thoughtfully with attention to equity considerations and appropriate infrastructure prerequisites. Rather than assuming universal internet access, educational technology strategies should leverage diverse platforms including mobile phones, radio, television, and offline digital resources. Investment in digital literacy for both teachers and students ensures that technology enhances rather than complicates learning processes.

Data systems and monitoring mechanisms enable evidence-based policymaking and continuous improvement of educational quality. Regular learning assessments, teacher evaluations, and school inspections generate information necessary to identify problems and measure intervention effectiveness. Public transparency regarding educational outcomes creates accountability and enables communities to advocate for improvements.

Community engagement and local ownership strengthen educational systems by ensuring that schools respond to community needs and values. Structures that enable parent and community participation in school governance, including decisions about resource allocation, teacher performance, and curriculum implementation, improve accountability and relevance. Community mobilization around the value of education, particularly for girls, can shift cultural norms that limit educational access.

Regional cooperation and knowledge sharing allow African countries to learn from each other's successes and challenges. The African Union and regional economic communities provide platforms for sharing best practices, harmonizing standards, and coordinating responses to transnational challenges. South-South cooperation enables African educators and policymakers to adapt solutions from countries with similar contexts rather than relying exclusively on Western models.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What percentage of children in Africa do not attend school regularly?

Approximately 98 million children and adolescents across sub-Saharan Africa remain out of school, according to UNESCO data from 2024, representing about one-third of the global out-of-school population. This includes children who have never enrolled and those who dropped out before completing their education.

Q: Why do girls face more barriers to education than boys in many African countries?

Girls encounter multiple interconnected obstacles, including cultural norms that prioritize boys' education, early marriage and pregnancy, household responsibilities, safety concerns related to sexual harassment and gender-based violence, and economic pressures that lead families to prioritize limited resources for sons' schooling.

Q: How does teacher shortage affect education quality in Africa?

Sub-Saharan Africa requires approximately 15 million additional teachers by 2030 to achieve universal education, according to UNESCO. Current shortages result in overcrowded classrooms, often exceeding 60 students per teacher, making individualized instruction impossible and severely compromising learning quality for all students.

Q: What is learning poverty, and how prevalent is it in Africa?

Learning poverty refers to the percentage of ten-year-old children unable to read and understand a simple text, and it affects approximately 89 percent of children in sub-Saharan Africa, according to World Bank estimates. This metric demonstrates that school attendance does not automatically translate into meaningful learning outcomes when quality issues remain unaddressed.

Q: How has the digital divide affected African students' education?

Only about 33 percent of Africa's population has internet access, according to the International Telecommunication Union, with much lower rates in rural areas. Many schools lack electricity, making digital learning integration impossible. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted this divide when school closures and remote learning left the vast majority of African students unable to continue their education online.

Q: Which African countries have made the most progress in improving educational access?

Countries including Kenya, Rwanda, Botswana, and most North African nations have achieved substantial improvements in educational enrollment and quality through policy reforms, increased investment, and targeted interventions addressing specific barriers. Their experiences demonstrate that progress is achievable with appropriate strategies and resource allocation.

Q: What economic impacts result from limited educational access in Africa?

Educational deficits cost the continent billions of dollars annually through lost productivity, reduced economic output, limited innovation capacity, and inability to compete effectively in global markets. The World Bank estimates that children born in sub-Saharan Africa today will achieve only 40 percent of their potential productivity as future workers compared to benchmarks of complete education and full health.

Q: How can technology help improve education in Africa despite infrastructure limitations?

Innovative approaches, including mobile learning platforms that function on basic phones, radio and television-based instruction, solar-powered digital classrooms, and offline educational content, provide alternatives to conventional technology models that assume reliable electricity and internet access. These contextually appropriate solutions can expand access and improve quality despite infrastructure challenges.

Q: What role do conditional cash transfers play in improving school attendance?

Conditional cash transfer programs provide financial incentives to poor families who keep children in school, addressing economic barriers to education. These initiatives, successfully implemented in countries including Kenya, Ghana, and South Africa, have demonstrated significant increases in enrollment and attendance while reducing child labor and early marriage rates.

Q: Why is mother-tongue instruction important for learning outcomes?

Research consistently shows that children learn most effectively in their mother tongue during early primary years. Educational systems that begin with mother-tongue instruction before gradually transitioning to official languages achieve better learning outcomes than those imposing foreign languages from the beginning, as demonstrated by countries including Ethiopia that have implemented this approach.

The lack of access to quality education in Africa represents a complex crisis with deep roots in economic constraints, infrastructure deficits, social inequalities, and systemic quality challenges. While the obstacles are substantial, the combination of growing political will, innovative solutions, increased understanding of effective interventions, and recognition of education's centrality to development creates realistic pathways toward improvement. Progress will require sustained commitment, adequate financing, evidence-based policymaking, and comprehensive strategies that address multiple barriers simultaneously. The stakes could not be higher, as educational outcomes will fundamentally shape Africa's trajectory in the coming decades, determining whether the continent harnesses its demographic potential for inclusive prosperity or faces continued marginalization in an increasingly knowledge-based global economy.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚