John Jacob Astor's Fur and Real Estate Empire: How America's First Multimillionaire Built His Fortune

Discover how John Jacob Astor built a $121B fortune through fur trading and Manhattan real estate. America's first multimillionaire's complete business story.

WEALTHY FAMILYEMPIRES/HISTORYUSAENTREPRENEUR/BUSINESSMAN

Shiv Singh Rajput

1/21/202613 min read

From German Immigrant to America's Wealthiest Man

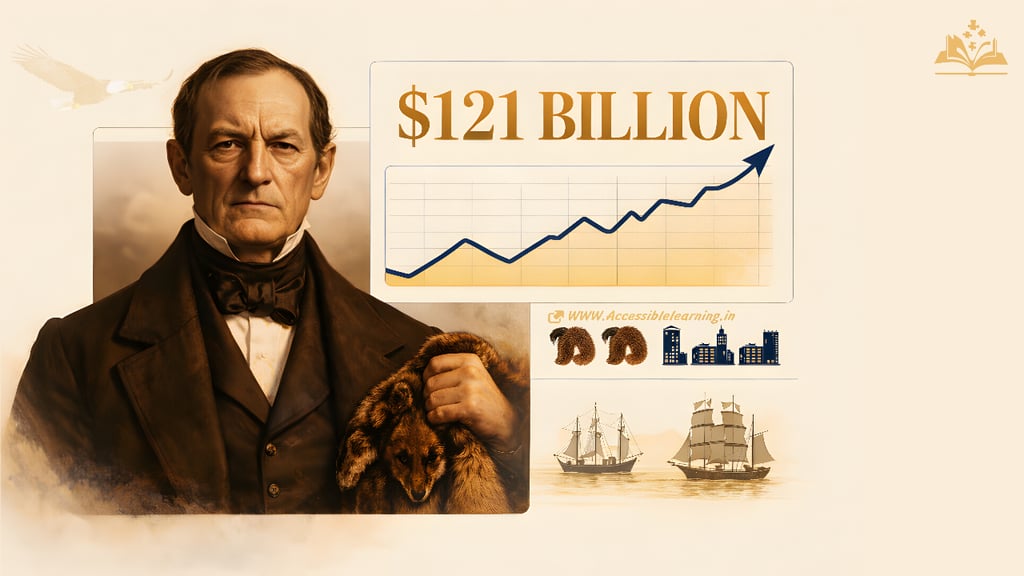

John Jacob Astor (1763-1848) transformed himself from a poor German butcher's son into America's first multimillionaire, creating a business empire that revolutionized both the fur trade and New York City's real estate landscape. His estimated $25 million fortune at death—equivalent to approximately $121 billion in today's dollars—represented nearly 1% of the entire United States GDP at the time, making him one of the richest individuals in modern history.

Born Johann Jakob Astor in Walldorf, Germany, near Heidelberg, this entrepreneurial genius arrived in America with little more than ambition and seven flutes. Through strategic vision, relentless perseverance, and shrewd business tactics, Astor built a transcontinental fur trading monopoly before pivoting to Manhattan real estate development that shaped the modern cityscape we know today.

The Fur Trade Empire: Building America's First Business Monopoly

Early Beginnings in the North American Fur Trade

Astor's journey into the fur business began serendipitously during his 1783 voyage to America, when he met a fur trader who introduced him to the lucrative potential of the North American fur trade. After briefly working in his brother Henry's New York butcher shop, Astor began purchasing raw beaver and other animal pelts from Native Americans, preparing them himself, and reselling them at substantial profits in European markets.

The fur trade in the late 18th century was driven by European fashion demand, particularly for beaver-fur men's hats that dominated style across the continent. Astor recognized this opportunity and opened his own fur goods shop in New York City in the late 1780s, simultaneously serving as the New York agent for his uncle's musical instrument business.

Strategic Expansion: The Jay Treaty Advantage

The 1794 Jay Treaty between Great Britain and the United States proved transformational for Astor's business. This diplomatic agreement opened previously restricted markets in Canada and the Great Lakes region, allowing American traders unprecedented access to prime fur-trapping territories.

Astor immediately capitalized on this opportunity by establishing a contract with the Montreal-based North West Company, which competed directly with the London-based Hudson's Bay Company. He imported furs from Montreal to New York and shipped them to European markets, particularly London, where demand remained consistently high.

By 1800—just 17 years after arriving in America—Astor had amassed over $250,000 (approximately $4.6 million in 2024 dollars) and emerged as one of the leading figures in the North American fur trade. His agents operated throughout western territories, employing ruthless competitive tactics that eliminated rivals and secured advantageous trading relationships with Native American tribes.

The American Fur Company: Creating a Transcontinental Monopoly

With presidential support from Thomas Jefferson, who enthusiastically endorsed American control of the fur trade within U.S. territories, Astor established the American Fur Company on April 6, 1808. Jefferson wrote to Astor expressing "great satisfaction" with merchants forming companies to undertake Indian trade within American territories, recognizing the strategic importance of domestic control over this lucrative industry.

Astor created two powerful subsidiaries to execute his vision:

Pacific Fur Company: Established to dominate the Columbia River region and Pacific Northwest trade, this subsidiary founded Fort Astoria in April 1811 at the mouth of the Columbia River in present-day Oregon. Fort Astoria became the first United States community on the Pacific coast, representing American territorial and commercial interests in the Oregon Country.

Southwest Fur Company: Designed to control the Great Lakes fur trade, this subsidiary included Canadian partners and operated throughout the upper Missouri River region, eventually establishing dominance across the Rocky Mountains.

Astor's strategic vision included a revolutionary triangular trade route: ships from New York would carry trade goods and supplies to the Pacific coast establishment, load furs gathered from Western tribes, transport them to China for sale, then return to New York with cargoes of tea, silk, and other Oriental goods. This global supply chain demonstrated business sophistication far ahead of contemporary practices.

The China Trade Connection

Beginning in 1800, Astor expanded beyond North American markets by trading directly with China at the port of Canton. Following the example of the Empress of China—the first American trading vessel to reach China—Astor exported furs but also traded sandalwood, tea, and, controversially, opium, significantly benefiting from Chinese demand for these commodities.

This China trade diversification proved crucial to Astor's wealth accumulation, as it reduced dependence on European fashion trends and provided additional revenue streams that financed his expanding business operations.

Challenges and Strategic Exit from Fur Trading

The War of 1812 temporarily disrupted Astor's fur empire. The Pacific Fur Company's Fort Astoria fell to British forces during the conflict, and the U.S. Embargo Act of 1807 had already complicated his import/export operations by closing trade with Canada.

Despite these setbacks, the American Fur Company grew into an economic powerhouse during the 1820s, employing over 750 men (not including Native American traders) and collecting annual fur harvests worth approximately $500,000—making it one of America's largest companies.

However, Astor demonstrated remarkable foresight by recognizing changing market conditions. As European fashion shifted away from beaver fur hats and clothing in the late 1820s, demand declined precipitously. Rather than watching his empire crumble, Astor sold his fur trading interests in 1834, at the peak of his monopoly control, and redirected his vast capital toward what he correctly identified as the next great American opportunity: New York City real estate.

The Real Estate Empire: Building Manhattan's Foundation

Early Real Estate Investments (1799-1819)

Astor's real estate journey began modestly in 1789, when he purchased his first Manhattan property at just 26 years old—a lot on the corner of Bowery Lane and Elizabeth Street—on the advice of his brother Henry. However, real estate remained secondary to his fur trade operations during these early years.

His strategic real estate accumulation accelerated after 1800, when China trade profits provided substantial capital for investment. In 1803, Astor purchased a significant 70-acre farm property between 42nd and 46th Streets, running from Broadway to the Hudson River, where he built the Astor Mansion at Hellgate.

One particularly notable early acquisition came from the estate of Aaron Burr after his infamous 1804 duel with Alexander Hamilton. Astor purchased Burr's Richmond Hill estate and strategically subdivided the land, making substantial profits from selling or leasing individual parcels—a tactic that would become his signature real estate strategy.

By 1819, Astor had invested approximately $715,000 (roughly $12 million in 2010 dollars) in Manhattan real estate, representing most of his liquid capital in a calculated bet on the city's growth trajectory.

Social Connections and Political Influence

Astor's business success was amplified by strategic social relationships that provided access to New York's upper echelons despite his rough immigrant manners (he was infamous for wiping his mouth on dining neighbors' sleeves). He became a Freemason, where he connected with Governor George Clinton, purchased a share of the prestigious Tontine Coffeehouse, and cultivated important friendships with Stephen Van Rensselaer and Aaron Burr.

These connections proved invaluable for his real estate dealings, providing insider information on city development plans, access to distressed properties, and political support for his ventures.

The 1830s Pivot: Full Focus on Real Estate Development

When Astor exited the fur trade in 1834, he possessed unrivaled capital and a visionary understanding of Manhattan's development potential. He correctly predicted that New York would emerge as one of the world's greatest cities, anticipating the northward expansion of development beyond the existing city limits.

Between 1819 and 1834, Astor invested an additional $445,000 acquiring real estate and buildings throughout Manhattan, particularly in areas that seemed worthless to contemporary observers but which Astor recognized would become prime locations as the city expanded.

Astor's Real Estate Business Model

Astor's approach to real estate development was systematic and ruthlessly efficient:

Long-Term Leasing Strategy: Rather than selling properties outright, Astor signed tenants to long-term leases, typically 21 years. This provided steady income while retaining land ownership and appreciation potential.

Tenant-Funded Improvements: If tenants wished to construct houses on leased land, they did so at their own expense. When leases expired, Astor either purchased the improvements at his own lowball valuations or renewed leases at dramatically increased rental rates.

Strategic Land Banking: Astor accumulated vast undeveloped tracts, waiting patiently for the city to expand toward his holdings. This required both capital reserves and confidence in long-term growth projections that most contemporaries lacked.

Strict Enforcement: Astor showed no leniency to tenants in arrears, promptly foreclosing on mortgages he controlled when property owners couldn't maintain payments. This earned him a reputation as shrewd and hard-hearted but protected his investments.

Opportunistic Acquisitions: During economic downturns, particularly after 1819, Astor aggressively purchased distressed properties at rock-bottom prices. When interest rates climbed to 7% and property owners defaulted, Astor foreclosed on scores of valuable Manhattan properties.

Major Real Estate Developments

Lafayette Place/Astor Place: Perhaps Astor's most significant development project centered on Lafayette Place (later Lafayette Street). In 1825, he petitioned the Common Council to open a north-south road through his property from Great Jones Street to Art Street, later extending to 8th Street. Named after the Marquis de Lafayette during his triumphal 1824-25 visit to America, this street became an Astor family domain where his son William built his mansion.

Astor donated $400,000 and land at the corner of Lafayette Place and Art Street (later renamed Astor Place) to establish the Astor Library, his primary philanthropic legacy. This library eventually became part of the New York Public Library system.

Astor House Hotel: Astor poured significant resources into constructing Astor House (1834-36) on Broadway at Vesey Street, creating New York's first luxury hotel. This quintessential urban building type established the foundation for the Astor family's hotel dynasty, which would later include the Hotel Astor (Times Square), the New Netherland Hotel (Fifth Avenue and 59th Street), the Waldorf (Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street), and the famous Waldorf-Astoria (Park Avenue at 50th Street).

Times Square Holdings: Astor's strategic purchases included significant land parcels that would eventually become Times Square, demonstrating his uncanny ability to identify future commercial centers.

West Side Midtown: Astor acquired most of his holdings in the rapidly developing West Side of Midtown Manhattan, positioning himself to profit enormously as the city expanded northward along the island.

Property Valuation Strategies

Contemporary critics accused Astor of acquiring properties at unfairly low prices. The now-defunct Court of Chancery occasionally forced him to pay additional money for undervalued lots. In one notorious case, he purchased an entire Harlem city block estimated to be worth $1 million for merely $2,000.

Astor's Wealth in Historical Context

Wealth at Death and Modern Equivalents

When John Jacob Astor died on March 29, 1848, at age 84, his estate was valued between $20 and $30 million. This represented approximately 0.9% to 1.35% of the entire United States GDP—an almost incomprehensible concentration of wealth in a single individual.

Adjusted for inflation using various methodologies, Astor's wealth at death translates to:

$121 billion (standard inflation adjustment)

$167-172 billion (GDP ratio adjustment)

$110-168 billion (various economic models)

Contemporary observer Nathaniel P. Tallmadge popularized the saying during his 1839-1840 Senate campaign that "one in every 100 dollars in this country ends up in J. Astor's hands," illustrating Astor's economic dominance.

Comparison to Modern Billionaires

To contextualize Astor's wealth, he ranks among history's richest individuals when adjusted for economic changes:

John D. Rockefeller: $435 billion (controlled 90% of American oil)

Andrew Carnegie: $375 billion (steel industry magnate)

Cornelius Vanderbilt: $185-200 billion (railroads and shipping)

John Jacob Astor: $121-172 billion (fur trade and real estate)

Bill Gates (peak 1999): $136-191 billion (technology)

Astor's wealth concentration as a percentage of GDP rivals or exceeds most modern billionaires, making him one of the wealthiest Americans relative to the overall economy.

Legacy and Lasting Impact

Family Wealth Continuity

Astor left the bulk of his fortune to his second son, William Backhouse Astor, as his eldest son, John Jr. was sickly and mentally unstable. William continued building the family fortune through real estate development and strategic investments.

The Astor family wealth and influence extended through multiple generations:

John Jacob Astor III: Peak net worth over $3 billion (2024 dollars)

John Jacob Astor IV: $4.8 billion at death (perished on the Titanic in 1912)

Vincent Astor: Inherited the majority of Astor IV's fortune and became known for social conscience and philanthropy

Influence on New York City Development

Astor's real estate empire fundamentally shaped Manhattan's physical development. By the time of his death, he was the largest landowner in New York City, owning vast portions of Manhattan from Lower Broadway through Midtown and beyond.

His development strategies—particularly long-term land banking and strategic leasing—became models for subsequent real estate developers. The Astor family's extensive Manhattan holdings continued influencing the city's development well into the 20th century, particularly in the theater district around Times Square.

Philanthropic Contributions

Despite his reputation for ruthlessness in business, Astor made several significant philanthropic contributions:

Astor Library: $400,000 donation plus land, later incorporated into the New York Public Library

German Society of the City of New York: $20,000 in gifts during his presidency (1837-1841)

Various educational institutions and charities

Places Named After Astor

Astor's legacy lives on in numerous geographical names:

Astor Place (Manhattan, New York City)

Astoria, Oregon (named after Fort Astoria and Astor's Pacific Fur Company)

Astoria neighborhood (Queens, New York City)

Astor Park (Green Bay, Wisconsin)

Town of Astor (Wisconsin, founded 1835)

Various streets, schools, and establishments across North America

Cultural Impact

Astor has been depicted in various media representations and historical works:

Herman Melville used Astor as a symbol of early American fortunes in the short story "Bartleby, the Scrivener."

Washington Irving's book "Astoria" chronicled the founding of Fort Astoria, financed by Astor

Anderson Cooper and Katherine Howe's "Astor: The Rise and Fall of an American Fortune" traces the family dynasty

Business Strategy Lessons

Astor's success provides enduring business principles:

Diversification: Transitioning from fur trade to real estate when market conditions changed

Strategic Vision: Recognizing Manhattan's growth potential before others

Global Thinking: Creating transcontinental and international trade networks

Patient Capital: Long-term land banking and lease strategies

Relationship Building: Cultivating political and social connections

Opportunistic Acquisitions: Buying distressed assets during economic downturns

Market Timing: Exiting the fur trade at its peak value

The American Dream Personified

John Jacob Astor's remarkable journey from a poor German butcher's son to America's first multimillionaire and wealthiest citizen exemplifies the entrepreneurial spirit and opportunity that defined early American capitalism. His fur trading empire demonstrated the potential for creating transcontinental business networks, while his Manhattan real estate investments literally shaped the physical development of America's greatest city.

Astor's legacy extends far beyond personal wealth accumulation. His business strategies—from creating America's first monopoly to pioneering modern real estate development techniques—influenced generations of entrepreneurs. His story represents both the promise and the complexity of American capitalism: extraordinary wealth creation through vision and perseverance, but also ruthless competition and exploitation that characterized the era.

On his deathbed in 1848, Astor reportedly exclaimed, "Could I begin life again, knowing what I now know, and had money to invest, I would buy every foot of land on the island of Manhattan." This quote captures both his prescient understanding of real estate value and his singular focus on wealth accumulation that made him a legend in American business history.

Today, with an inflation-adjusted fortune of $121-172 billion, John Jacob Astor remains one of the wealthiest individuals in human history, his name forever synonymous with American success, ambition, and the transformative power of strategic vision combined with relentless execution.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How did John Jacob Astor make his money?

John Jacob Astor built his fortune primarily through two industries: the North American fur trade and Manhattan real estate development. He first established a fur trading monopoly through his American Fur Company (founded 1808), which controlled trade from the Great Lakes to the Pacific Northwest and traded with China. After recognizing declining demand for beaver fur in the 1830s, he sold his fur interests and invested heavily in New York City real estate, purchasing vast tracts of Manhattan land that appreciated enormously as the city expanded northward.

Q: What was John Jacob Astor's net worth at death?

At his death in 1848, John Jacob Astor's estate was valued at $20-30 million, making him the wealthiest person in the United States. Adjusted for inflation and economic growth, this translates to approximately $121-172 billion in today's dollars, representing nearly 1% of the entire U.S. GDP at that time.

Q: Was John Jacob Astor America's first millionaire?

Yes, John Jacob Astor is recognized as America's first multimillionaire. He achieved millionaire status by 1800 through his fur trading operations and became the first person in United States history to accumulate wealth exceeding multiple millions of dollars, setting the foundation for the concept of extreme wealth in American society.

Q: How did the American Fur Company work?

The American Fur Company, founded by Astor in 1808, operated through two main subsidiaries: the Pacific Fur Company (controlling the Columbia River and Pacific Northwest) and the Southwest Fur Company (dominating the Great Lakes region). The company employed over 750 men plus Native American traders by the 1820s, established trading posts across the continent, and created a global supply chain connecting North America, China, and Europe. Astor's agents gathered furs from trappers and Native Americans, which were then shipped to Chinese and European markets, generating annual revenues of approximately $500,000.

Q: What real estate did John Jacob Astor own in New York?

By his death in 1848, Astor was Manhattan's largest landowner, with holdings including properties from 42nd to 46th Streets between Broadway and the Hudson River, extensive West Side Midtown parcels, land that would become Times Square, the Lafayette Place/Astor Place area, the Astor House hotel on Broadway, properties throughout Lower Manhattan, and numerous parcels from New Jersey to Oregon. His real estate strategy focused on buying undeveloped land in the path of the city's northward expansion, then leasing it long-term rather than selling.

Q: Why did John Jacob Astor exit the fur trade?

Astor sold his fur trading interests in 1834 because European fashion trends shifted away from beaver-fur hats and clothing, causing demand to decline significantly. Demonstrating remarkable business foresight, he recognized the changing market conditions and chose to sell at the peak of his monopoly control rather than riding the industry into decline. He then redirected his capital toward Manhattan real estate, which he correctly predicted would generate superior returns.

Q: How much would John Jacob Astor be worth today?

Using various economic adjustment models, John Jacob Astor's $20-30 million estate at death (1848) would equal approximately $121-172 billion in 2024 dollars. His wealth represented 0.9-1.35% of the entire U.S. GDP at the time, making him proportionally wealthier relative to the economy than most modern billionaires. This places him among the top 5-10 wealthiest Americans in history when adjusted for inflation and economic growth.

Q: What happened to the Astor fortune after John Jacob died?

Astor left the majority of his fortune to his second son, William Backhouse Astor, who continued expanding the family's real estate holdings. The wealth passed through multiple generations, including John Jacob Astor III ($3+ billion in today's dollars) and John Jacob Astor IV ($4.8 billion, died on the Titanic in 1912). Vincent Astor inherited the majority of Astor IV's fortune and became known for philanthropic activities. While the family remained wealthy for generations, the fortune eventually dispersed through inheritance divisions, philanthropy, and changing economic conditions.

Q: Did John Jacob Astor have a monopoly?

Yes, the American Fur Company is considered the first American business monopoly. By 1830, Astor's company controlled virtually all fur trading in the United States, from the Great Lakes through the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Northwest. He achieved this through aggressive tactics, including buying out small competitors, undercutting rivals on pricing, establishing exclusive trading relationships with Native American tribes, and leveraging political connections, including presidential support from Thomas Jefferson.

Q: What business lessons can we learn from John Jacob Astor?

Key lessons from Astor's success include recognizing and acting on market timing (selling the fur business at its peak), diversifying into new industries before old ones decline, thinking globally and creating international trade networks, building strategic political and social relationships, practicing patient capital deployment through long-term investments, acquiring distressed assets during economic downturns, and maintaining focus on long-term vision rather than short-term fluctuations. His ability to foresee New York's growth and reposition his entire business model demonstrates adaptability and strategic vision.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚