50 Million in Poverty: Understanding and Addressing Wealth Inequality Across Brazil and Latin America

Explore wealth inequality and poverty gaps in Brazil and Latin America with the latest data, structural causes, policy solutions, and socioeconomic impacts on millions.

USAPOLITICAL JOURNEYEUROPEAN UNIONAWARE/VIGILANT

Keshav Jha / Kim Shin

10/7/202518 min read

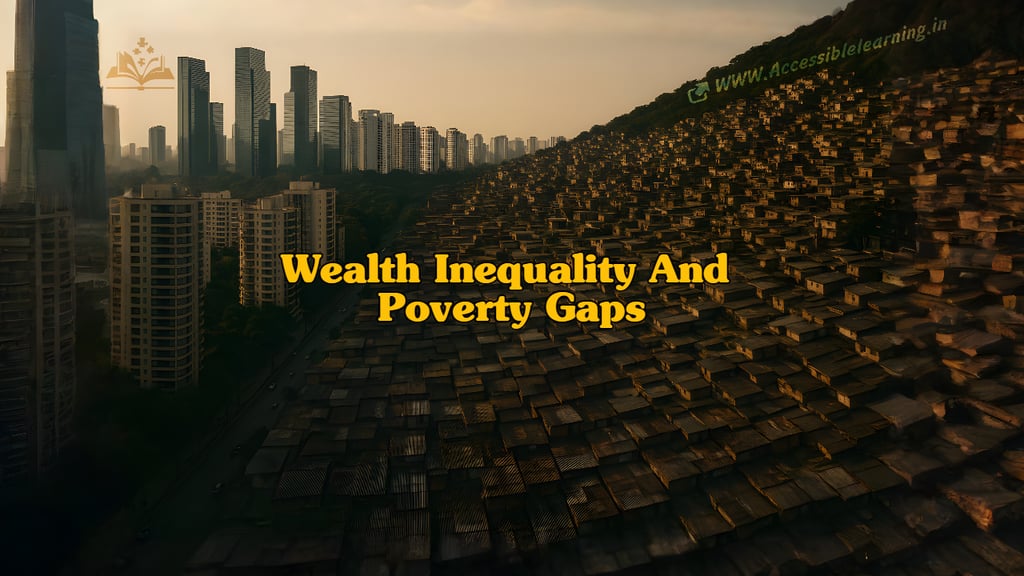

The stark divide between the wealthy and the poor in Latin America represents one of the most pressing socioeconomic challenges of the 21st century. Brazil, as the region's largest economy, exemplifies these disparities while simultaneously offering insights into potential pathways toward greater equity. Understanding the depth and complexity of wealth inequality in this region requires examining historical foundations, current statistical realities, and the structural factors that perpetuate economic division.

Understanding the Scale of Wealth Inequality in Latin America

Latin America holds the distinction of being the most unequally distributed region in the world when measuring wealth concentration. According to recent data from the World Inequality Database and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the wealthiest ten percent of the population controls approximately 77 percent of the region's total wealth, while the bottom half possesses merely two percent. This extreme concentration creates profound social, economic, and political ramifications that touch every aspect of daily life for millions of people.

Brazil demonstrates particularly striking disparities within this already unequal region. The country's Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality on a scale where zero represents perfect equality and one represents complete inequality, has fluctuated between 0.52 and 0.54 in recent years. Despite some improvements during the early 2000s, Brazil remains among the ten most unequal countries globally. The wealthiest one percent of Brazilians possess approximately 49 percent of the nation's total wealth, creating a concentration of resources that limits economic mobility and perpetuates intergenerational poverty.

The poverty gap in Brazil and Latin America extends beyond simple income measurements. Multidimensional poverty indicators reveal that access to quality education, healthcare, adequate housing, and basic services remains severely restricted for substantial portions of the population. In Brazil, approximately 50 million people live below the poverty line, with nearly 13 million experiencing extreme poverty and surviving on less than two dollars per day. These numbers represent not merely statistics but human lives constrained by limited opportunities and restricted access to resources that could enable upward mobility.

Historical Foundations of Economic Disparity

The roots of contemporary wealth inequality in Latin America trace back centuries to colonial economic structures that concentrated land ownership and resource extraction among small elites. The encomienda and hacienda systems established patterns of wealth concentration that persisted long after independence movements swept across the continent. These historical arrangements created enduring institutions and social hierarchies that continue to influence wealth distribution in modern times.

Brazil's particular history of slavery, which lasted longer than in most other nations in the Americas, established deep-rooted racial inequalities that intersect with economic disparities. The absence of comprehensive land reform following abolition in 1888 meant that formerly enslaved people and their descendants faced systematic exclusion from property ownership and economic opportunity. Today, Black and mixed-race Brazilians experience poverty at rates nearly double those of white Brazilians, demonstrating how historical injustices compound across generations to create persistent wealth gaps.

Throughout the 20th century, periods of industrialization and economic growth in Latin America often failed to translate into broadly shared prosperity. Import substitution industrialization policies created economic growth but also reinforced existing inequalities through limited labor market participation and insufficient investment in universal education and healthcare systems. Military dictatorships in many countries, including Brazil's 1964 to 1985 period, implemented economic policies that prioritized growth over distribution, further widening the gap between economic classes.

Contemporary Factors Perpetuating Inequality

The structure of Latin American labor markets contributes significantly to ongoing wealth disparities. Informal employment, which accounts for approximately 53 percent of total employment in the region, provides workers with neither the stability nor the benefits associated with formal sector positions. In Brazil, roughly 40 percent of workers operate in the informal economy, lacking access to social security, unemployment insurance, or labor protections. This informality creates persistent vulnerability and limits wealth accumulation among lower-income populations.

Tax structures across Latin America generally place disproportionate burdens on consumption rather than wealth or high incomes, creating regressive systems that fail to redistribute resources effectively. Brazil collects approximately 33 percent of GDP in taxes, yet the tax system relies heavily on indirect taxes that affect all consumers equally regardless of income level. Wealthy individuals often benefit from numerous exemptions and loopholes, particularly regarding capital gains and inheritance. The effective tax rate on the wealthiest Brazilians remains lower than that faced by middle-class workers, perpetuating rather than ameliorating inequality.

Education systems throughout the region reflect and reinforce existing inequalities. Public education quality varies dramatically, with schools in wealthier areas receiving better resources and producing superior outcomes compared to those serving poor communities. In Brazil, students from the wealthiest quintile score approximately 100 points higher on international assessments than those from the poorest quintile, a gap equivalent to roughly three years of schooling. Private education, accessible primarily to affluent families, provides advantages that compound across generations, creating barriers to social mobility.

Access to credit and financial services remains severely constrained for poor and working-class Latin Americans. Traditional banking systems often exclude those without formal employment or substantial assets, forcing many to rely on informal lending with prohibitive interest rates. This financial exclusion prevents low-income individuals from investing in education, starting businesses, or building assets that could lift families out of poverty. In Brazil, despite growth in financial inclusion initiatives, millions remain unbanked or underbanked, limiting their economic opportunities.

Regional Variations and Comparative Perspectives

While Brazil exemplifies many regional trends, significant variations exist across Latin America regarding wealth distribution and poverty rates. Uruguay and Argentina have historically maintained more equitable distributions than Brazil, though both have experienced setbacks in recent years due to economic crises and policy shifts. Countries in Central America and parts of the Andean region demonstrate even more severe inequalities than Brazil, with Guatemala and Honduras showing particularly extreme wealth concentrations.

Chile presents an interesting case within the region, having achieved substantial economic growth and poverty reduction over recent decades while simultaneously maintaining high levels of inequality. The country's Gini coefficient remains elevated at approximately 0.45, and recent social unrest has highlighted public dissatisfaction with persistent disparities despite overall economic progress. These tensions demonstrate that economic growth alone proves insufficient without deliberate policies to ensure broadly shared benefits.

Mexico, as another major regional economy, faces challenges similar to Brazil regarding informal employment and limited social mobility. The country's northern states show markedly different economic profiles compared to southern regions, where indigenous populations experience poverty rates exceeding 70 percent in some areas. This geographic dimension of inequality adds additional complexity to poverty reduction efforts, as national policies must address vastly different regional realities.

Impact on Social Cohesion and Development

Extreme wealth inequality generates consequences that extend far beyond individual economic hardship. High inequality correlates with reduced social trust, increased crime rates, and political instability throughout Latin America. In Brazil, violence disproportionately affects poor communities, with homicide rates in favelas far exceeding those in affluent neighborhoods. This violence both results from and reinforces inequality, creating cycles of disadvantage that prove difficult to break.

Health outcomes demonstrate stark disparities along economic lines. Life expectancy in wealthy Brazilian neighborhoods exceeds that in poor areas by more than ten years. Infant mortality, malnutrition, and chronic disease prevalence all show dramatic gradients based on socioeconomic status. The COVID-19 pandemic starkly revealed these inequalities, as poor communities experienced substantially higher infection and mortality rates while having less access to healthcare and facing greater difficulty adhering to social distancing measures due to crowded housing and informal employment requirements.

Educational outcomes, already unequal, face further strain due to wealth disparities. Children from poor families begin school with developmental disadvantages due to inadequate nutrition and limited early childhood stimulation. Schools serving these communities struggle with insufficient resources, less experienced teachers, and higher dropout rates. By adolescence, many young people from low-income families have left formal education entirely to contribute to household income, perpetuating intergenerational poverty cycles.

Policy Approaches and Reform Efforts

Brazil's Bolsa Família program, established in 2003 and later expanded and renamed Auxílio Brasil, represents one of the most significant conditional cash transfer initiatives globally. At its peak, the program reached approximately 14 million families, providing monthly stipends conditional on children attending school and receiving health checkups. Research demonstrates that such programs successfully reduce extreme poverty and improve educational and health outcomes for participating families. However, these transfers prove insufficient alone to address deeper structural inequalities without complementary policies targeting wealth accumulation and economic opportunity.

Progressive taxation reforms have gained attention as potential tools for reducing inequality, though implementation faces substantial political resistance throughout the region. Proposals include wealth taxes, higher rates on top incomes, and elimination of regressive exemptions benefiting the wealthy. Argentina implemented a one-time wealth tax in 2020 that generated significant revenue, though questions remain about long-term sustainability and potential capital flight. Brazil continues debating tax reform proposals that would shift burdens toward higher incomes and wealth, though powerful interests maintain status quo arrangements that favor the affluent.

Land reform initiatives, though politically contentious, offer potential pathways toward greater equity in predominantly rural areas. Brazil's landless workers movement has pushed for redistribution of unused large estates to poor families, with mixed results. Where implemented, agrarian reform has provided land access and improved livelihoods for previously landless families, though programs often suffer from insufficient support services, credit access, and infrastructure investment. Urban land reform, addressing housing inequality in cities, has received less attention despite rapid urbanization making it increasingly relevant.

Expanding quality public education represents perhaps the most critical long-term strategy for reducing inequality and increasing social mobility. Several Latin American countries, including Chile and Mexico, have implemented major education reforms aimed at improving quality and equity. Brazil's education spending as a percentage of GDP exceeds many developed nations, yet quality remains inconsistent and outcomes unequal. Successful reforms require not merely increased funding but also improved teacher training, better resource allocation, and genuine commitment to serving disadvantaged communities.

Labor Market Reforms and Economic Inclusion

Addressing labor market informality requires comprehensive approaches that combine incentives for formalization with enforcement mechanisms and support for small businesses and entrepreneurs. Some Latin American countries have experimented with simplified tax and regulatory regimes for small enterprises, reducing barriers to formal sector participation. Brazil implemented the Simples Nacional system, which consolidated multiple taxes into a single payment scheme with lower rates for small businesses. While this initiative has encouraged some formalization, informal employment remains widespread, particularly among the lowest-income workers.

Minimum wage policies have proven effective at reducing poverty when set at appropriate levels and enforced consistently. Brazil's minimum wage has increased substantially in real terms over the past two decades, contributing to poverty reduction and decreased inequality during the 2000s. However, current levels remain insufficient for families to achieve adequate living standards, particularly in high-cost urban areas. Regional minimum wage variations, which some economists advocate, could address cost-of-living differences while avoiding potential employment losses from nationally uniform rates set too high for poorer regions.

Strengthening labor unions and collective bargaining rights offers another avenue for improving worker outcomes and reducing inequality. Union density has declined throughout Latin America in recent decades, weakening workers' negotiating power. Countries that have maintained stronger labor protections and union participation, such as Uruguay, generally show more equitable income distributions. However, labor market protections must balance worker security with flexibility that enables employment growth, particularly for young workers and those seeking to enter formal employment.

The Role of Technology and Innovation

Digital technology presents both opportunities and challenges for addressing inequality in Latin America. Increased internet connectivity and smartphone adoption have expanded access to information, financial services, and economic opportunities for previously excluded populations. Mobile banking and digital payment systems have extended financial services to millions of unbanked individuals, facilitating savings, credit access, and formal sector participation. Brazil's PIX instant payment system, launched in 2020, has dramatically increased digital financial inclusion, processing billions of transactions monthly.

However, the digital divide creates new dimensions of inequality as access to technology and digital literacy become increasingly essential for economic participation. Rural areas and poor urban communities often lack reliable internet connectivity, limiting residents' ability to access online education, remote work opportunities, and digital services. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted these disparities as wealthy families transitioned to remote work and online education while poor families struggled without necessary technology or connectivity. Addressing digital inequality requires investment in infrastructure, affordable access, and digital literacy programs targeting disadvantaged communities.

The future of work, increasingly shaped by automation and artificial intelligence, poses particular challenges for Latin American labor markets. Many routine jobs currently providing livelihoods for middle- and lower-income workers face displacement risk from technological advancement. Without proactive policies to ensure workers can transition to new opportunities, technological change threatens to exacerbate existing inequalities. Education systems must evolve to prepare workers for jobs requiring creativity, complex problem-solving, and interpersonal skills that remain difficult to automate.

International Dimensions and Global Integration

Global economic integration has generated both opportunities and challenges for Latin American inequality. Trade liberalization has created export opportunities and attracted foreign investment, contributing to economic growth. However, benefits have been distributed unevenly, often favoring skilled workers and capital owners while displacing workers in sectors facing new competition. Brazil's integration into global value chains has generated prosperity for some while leaving others behind, contributing to regional inequalities within the country.

Remittances from emigrants represent significant income sources for many Latin American families, with flows exceeding 100 billion dollars annually to the region. These transfers provide crucial support for receiving families, often enabling improved housing, education, and healthcare. However, reliance on remittances also indicates underlying economic weaknesses that push workers to seek opportunities abroad, representing a loss of human capital for sending countries. Migration also separates families and creates social costs alongside economic benefits.

International cooperation and development assistance can support inequality reduction efforts, though aid flows to Latin America remain relatively modest compared to other developing regions. Multilateral institutions, including the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank provide financing and technical assistance for social programs and inclusive development initiatives. However, domestic political will and policy choices ultimately determine whether countries successfully address inequality and poverty, with external support playing a complementary rather than primary role.

Environmental Justice and Climate Considerations

Environmental degradation and climate change disproportionately affect poor communities throughout Latin America, adding another dimension to existing inequalities. Deforestation, water pollution, and air quality problems concentrate in low-income areas where residents lack political power to demand environmental protections. In Brazilian cities, favelas often occupy environmentally vulnerable locations, including hillsides prone to landslides and floodplains subject to inundation, placing residents at risk while wealthier neighborhoods enjoy safer locations.

Climate change threatens to exacerbate inequalities as extreme weather events, changing precipitation patterns, and rising temperatures affect agricultural productivity and water availability. Small-scale farmers and rural communities, already among the poorest populations, face particular vulnerability to climate impacts while lacking resources for adaptation. Urban poor populations also face heightened risks from heat waves, flooding, and disease spread, as crowded housing and inadequate infrastructure increase exposure and limit coping capacity.

Just transition approaches that address climate change while promoting equity represent important policy directions for Latin America. Investments in renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and green infrastructure can create employment opportunities while mitigating environmental damage. However, without deliberate attention to distributional consequences, climate policies risk imposing costs on poor communities while benefits accrue to the wealthy. Carbon pricing mechanisms, for instance, require careful design and complementary policies to avoid regressive impacts on low-income households.

Gender Dimensions of Inequality

Gender intersects with economic inequality throughout Latin America, with women experiencing poverty at higher rates and facing additional barriers to economic opportunity. Women earn approximately 20 percent less than men for similar work across the region, with gaps even larger for women of color and those with lower education levels. Labor force participation rates for women remain substantially below male rates, reflecting care responsibilities, discrimination, and limited access to supportive services, including childcare.

Female-headed households face particular economic vulnerability, as single mothers struggle to balance employment with care responsibilities while typically earning less than male counterparts. In Brazil, approximately 40 percent of families are headed by women, and these households experience poverty rates significantly exceeding those with male heads. Access to quality, affordable childcare represents a critical need for enabling mothers' labor force participation and economic security, yet public provision remains inadequate throughout the region.

Violence against women, pervasive throughout Latin America, generates economic consequences alongside human suffering. Women experiencing violence face reduced employment, lower earnings, and health costs that impair economic well-being. Children exposed to domestic violence experience developmental impacts affecting future educational and economic outcomes. Addressing gender-based violence requires not only criminal justice responses but also economic policies supporting women's independence and services assisting survivors.

Indigenous and Afro-descendant Communities

Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants experience disproportionate poverty throughout Latin America, reflecting historical marginalization and ongoing discrimination. In Brazil, poverty rates among Black and mixed-race populations exceed those of white Brazilians by more than 20 percentage points. Indigenous communities face even more severe disadvantages, with poverty rates approaching 80 percent in some areas. These disparities reflect educational inequalities, labor market discrimination, limited asset ownership, and geographic isolation from economic opportunities.

Land rights represent particularly crucial issues for indigenous communities, as territories provide not only economic livelihoods but also cultural and spiritual foundations. Resource extraction and agricultural expansion frequently encroach on indigenous lands, creating conflicts and threatening communities' well-being. Legal recognition and protection of indigenous territories offers both human rights imperatives and economic benefits, as indigenous communities often serve as effective environmental stewards whose lands show lower deforestation rates than surrounding areas.

Affirmative action policies in education and employment have emerged as strategies for addressing racial inequalities in Brazil and other countries. University quotas for Black, mixed-race, and indigenous students have increased representation in higher education, with evidence suggesting positive impacts on social mobility. However, these policies remain controversial and face ongoing legal and political challenges. Comprehensive approaches addressing systemic racism across institutions prove necessary for genuine equity, as affirmative action alone cannot overcome all barriers facing marginalized communities.

Political Economy and Power Structures

Understanding wealth inequality in Latin America requires examining political economy dynamics and power structures that shape policy decisions. Economic elites wield substantial political influence through campaign financing, media ownership, and direct participation in government. This influence often translates into policies favoring wealthy interests, including tax exemptions, subsidies, and regulations protecting established businesses from competition. Regulatory capture, where industries influence agencies meant to oversee them, further skews policy toward elite interests.

Corruption represents a pervasive challenge throughout the region, diverting public resources from productive uses and undermining trust in institutions. High-profile corruption scandals, including Brazil's Lava Jato investigation, have revealed systematic embezzlement and collusion between political and business elites. Such corruption both results from and reinforces inequality, as the wealthy exploit political connections while poor citizens lack voice or recourse when public services fail to materialize despite allocated funding.

Social movements and civil society organizations play crucial roles in advocating for more equitable policies and holding governments accountable. Landless workers' movements, urban housing activists, indigenous organizations, and other groups have achieved important victories in securing rights and resources for marginalized communities. However, activists often face harassment, violence, and criminalization, particularly when challenging powerful economic interests involved in land conflicts, resource extraction, or infrastructure projects.

Measuring Progress and Setting Goals

Tracking inequality and poverty requires robust data collection and transparent reporting systems. Latin American countries vary considerably in statistical capacity and data quality, with some nations maintaining comprehensive household surveys and administrative data while others lack reliable information. Brazil's Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística provides extensive data enabling detailed inequality analysis, though gaps remain regarding wealth measurement and certain vulnerable populations. Improving data systems throughout the region represents a necessary foundation for evidence-based policymaking.

The Sustainable Development Goals, adopted by United Nations member states in 2015, provide a framework for addressing poverty and inequality globally. Goal One targets ending poverty in all forms, while Goal Ten specifically addresses inequality reduction within and among countries. Latin American nations have committed to these goals, though progress varies substantially across countries and indicators. Regular monitoring and reporting on SDG indicators helps maintain political attention on these issues and enables international comparisons and learning.

Setting ambitious yet achievable targets for inequality reduction requires balancing aspirational goals with realistic assessments of political feasibility and resource constraints. Some countries have established explicit inequality reduction targets within national development plans, though implementation often lags behind stated objectives. Successful progress requires sustained political commitment across electoral cycles, adequate resource allocation, and genuine engagement with affected communities in policy design and implementation.

Comparative International Lessons

Examining international experiences with inequality reduction offers valuable insights for Latin America, though transferring policies across different contexts requires careful adaptation. Nordic countries achieved relatively equal income distributions through combinations of progressive taxation, robust social protection systems, universal public services, and strong labor market institutions. However, these systems developed over many decades within particular cultural and political contexts, making direct replication challenging.

Asian countries, including South Korea and Taiwan, reduced inequality during rapid economic development through land reforms, investments in universal education, and industrial policies promoting broadly shared growth. These experiences demonstrate that inequality reduction and economic development can proceed simultaneously rather than presenting necessary tradeoffs. However, these countries' specific historical circumstances, including geopolitical factors and authoritarian governance during key periods, differ substantially from contemporary Latin American contexts.

Within Latin America, countries that achieved the greatest inequality reduction combined targeted cash transfers with broader structural reforms. Uruguay maintained more equal income distribution through strong labor protections, expanded education access, and progressive tax reforms. While still facing challenges, Uruguay's experience suggests that sustained commitment to equity-oriented policies can generate results even within the region's difficult political economy constraints.

Future Outlook and Potential Trajectories

Latin America's demographic trends present both opportunities and challenges for addressing inequality. Declining fertility rates reduce dependency ratios, potentially enabling increased investments per child in education and health. However, rapid population aging will strain social protection systems designed when populations were younger. Brazil faces particularly acute aging dynamics, with projections indicating the elderly population will triple by 2050, requiring substantial expansions in pension systems and healthcare capacity.

Economic diversification beyond commodity exports offers potential pathways toward more inclusive development. Overreliance on natural resource extraction generates boom-bust cycles and concentrated wealth among resource owners while providing limited employment. Developing manufacturing, services, and knowledge-based industries could create broader employment opportunities and reduce vulnerability to commodity price fluctuations. However, achieving such diversification requires investments in infrastructure, education, and innovation ecosystems that remain underdeveloped in much of the region.

The COVID-19 pandemic's long-term consequences will shape inequality trajectories for years to come. The crisis reversed years of poverty reduction progress, pushing millions of Latin Americans back into poverty. School closures created learning losses that will affect lifetime earnings, with impacts concentrated among poor children who lacked resources for effective remote learning. Economic recovery patterns will determine whether the region emerges with reduced or exacerbated inequalities, depending on whether policies prioritize inclusive growth or favor rapid GDP expansion regardless of distributional consequences.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are the main causes of wealth inequality in Brazil and Latin America?

Wealth inequality in Brazil and Latin America stems from historical factors including colonial exploitation and slavery, structural economic issues such as informal employment and regressive taxation, limited access to quality education for poor communities, and political systems that often favor elite interests. These factors interact and reinforce each other across generations, creating persistent disparities that prove difficult to address without comprehensive policy reforms.

Q: How does Brazil's inequality compare to other Latin American countries?

Brazil ranks among the most unequal countries in Latin America, with a Gini coefficient typically ranging between 0.52 and 0.54. While some Central American nations and certain Andean countries show comparable or higher inequality levels, Brazil's absolute wealth concentration stands out given its status as the region's largest economy. Countries like Uruguay and Argentina have maintained more equitable distributions, though all Latin American nations face significant inequality challenges compared to global standards.

Q: What percentage of wealth does the top one percent own in Brazil?

The wealthiest one percent of Brazilians control approximately 49 percent of the nation's total wealth, according to recent estimates. This extreme concentration exceeds levels found in most developed nations and reflects both income inequality and disparities in asset ownership, including land, financial wealth, and business equity. The top ten percent collectively own approximately 75 percent of total wealth, leaving very little for the bottom half of the population.

Q: How many people live in poverty in Brazil?

Approximately 50 million Brazilians live below the poverty line, representing roughly 24 percent of the population. Within this group, nearly 13 million people experience extreme poverty, surviving on less than two dollars per day. These numbers have fluctuated over time, improving during the 2000s before worsening during recent economic crises and the COVID-19 pandemic, which pushed millions back into poverty after years of progress.

Q: What is the poverty gap, and how does it differ from the poverty rate?

The poverty gap measures the depth of poverty by calculating how far below the poverty line poor people's incomes fall on average, expressed as a percentage of the poverty line. This differs from the poverty rate, which simply counts what proportion of the population falls below the threshold. The poverty gap provides a more nuanced understanding of poverty severity, as it captures whether poor people live slightly below or far below the poverty line, information crucial for determining appropriate policy responses and resource requirements.

Q: Have any policies successfully reduced inequality in Latin America?

Conditional cash transfer programs like Brazil's Bolsa Família have successfully reduced extreme poverty and improved education and health outcomes for participating families. During the 2000s commodity boom, several Latin American countries combined social programs with minimum wage increases and expanded public services, achieving meaningful inequality reductions. Uruguay sustained these gains through strong labor protections and progressive taxation. However, progress has proven vulnerable to economic downturns and political changes, demonstrating that sustained commitment remains necessary.

Q: How does informal employment contribute to poverty in the region?

Informal employment, affecting approximately 53 percent of Latin American workers and 40 percent in Brazil, perpetuates poverty by denying workers access to social security, labor protections, unemployment insurance, and stable incomes. Informal workers typically earn substantially less than their formal sector counterparts and lack benefits that support wealth accumulation. This informality also limits tax collection, reducing public resources available for social programs that could address poverty and inequality.

Q: What role does education play in perpetuating wealth inequality?

Education systems reflect and reinforce existing inequalities as wealthy families access high-quality private schools while public schools serving poor communities struggle with inadequate resources and less experienced teachers. Students from affluent backgrounds score substantially higher on assessments and progress further in education, creating advantages that translate into better employment opportunities and higher lifetime earnings. This educational divide perpetuates intergenerational inequality as children inherit their parents' economic positions.

Q: How does racial inequality intersect with wealth inequality in Brazil?

Black and mixed-race Brazilians, who constitute the majority of the population, experience poverty at rates nearly double those of white Brazilians, reflecting historical legacies of slavery and ongoing discrimination. Racial disparities appear across all socioeconomic indicators, including income, wealth, education, employment, and health outcomes. These patterns demonstrate how racial and economic inequalities intersect and compound, requiring policies that address both dimensions simultaneously to achieve meaningful progress toward equity.

Q: What impact does wealth inequality have on crime and violence?

High wealth inequality correlates strongly with elevated crime rates and violence throughout Latin America. Brazil's homicide rates, among the world's highest, concentrate heavily in poor communities where limited economic opportunities, weak institutions, and inadequate public services create conditions conducive to criminal activity. Violence both results from inequality and perpetuates it by deterring investment, disrupting education, causing trauma, and forcing poor communities to divert resources toward security rather than productive uses.

The challenge of addressing wealth inequality and poverty gaps in Brazil and Latin America requires sustained commitment, comprehensive policy approaches, and genuine political will to prioritize equity alongside economic growth. Historical patterns and entrenched power structures create significant obstacles, yet successful experiences both within the region and internationally demonstrate that meaningful progress remains achievable. The path forward demands not only technical policy expertise but also social mobilization, political courage, and recognition that reducing inequality serves not only moral imperatives but also pragmatic interests in social stability, economic dynamism, and human development. As Latin America navigates demographic transitions, technological changes, and climate challenges in coming decades, how societies address these fundamental questions of distribution and opportunity will profoundly shape the region's trajectory and the well-being of hundreds of millions of people whose futures depend on more equitable access to resources, opportunities, and dignity.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

All © Copyright reserved by Accessible-Learning Hub

| Terms & Conditions

Knowledge is power. Learn with Us. 📚